Reference Biography: Walter O’Malley

The Political Game - Part 1

While success on the field warmed the cockles of O’Malley’s heart, he had heartburn from the political landscape in New York, warning those in charge that he would look elsewhere for his beloved Dodgers if a suitable piece of land on which to build his new stadium could not be located. Since 1947, O’Malley had unsuccessfully tried to gain the attention of the politicians and officials who could assist him in finding land so he could build a state-of-the-art ballpark in Brooklyn. His contact with architect Norman Bel Geddes began in earnest in 1947, as they studied possible scenarios to increase the seating capacity at Ebbets Field to 55,000. It was later determined that the costs of doing that, simply pouring money into an old structure with no growth potential, was not wise.

Among the 1955 The Sporting News “Men of the Year” are Dodger Manager Walter Alston, outfielder Duke Snider and team President Walter O’Malley.

As the Dodgers savored their success on the field, there were ongoing discussions for new ballpark sites.

Although O’Malley planned to stay in Brooklyn if the support and assistance by Wagner, Moses and City Councilman Abe Stark had been there, it wasn’t and he could not wait.

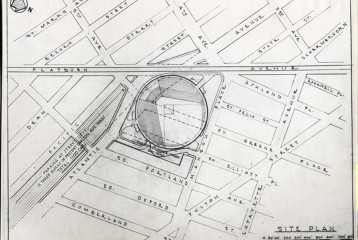

Moses disregarded numerous pleas from O’Malley to explore the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues site because of the complex land acquisition process that would be necessary. Moses was also concerned that it would take more than $100 million off the tax rolls, despite the run-down and congested area. O’Malley felt that the confluence of transportation (all major subways, Long Island Rail Road) to the ballpark would be a major boost to attendance and the surrounding areas. Ample parking could have been available in a connected structure, which would have benefited the entire area on non-game days and in the morning and afternoon hours when night games were scheduled. Moses repeatedly told a frustrated O’Malley that it wasn’t feasible or say “you can be sure that my boys will fully respect the wishes of the Board (of Estimate) and do everything possible to help.” Letter from Robert Moses to Walter O’Malley, August 15, 1955 But, nothing got off the ground. Moses was focused on the Flushing Meadows site in Queens, adjacent to the land used for New York’s 1939-40 World’s Fair. O’Malley even considered buying $5 million in bonds to help fund the $30 million Brooklyn Sports Center Authority’s proposed stadium, which would have made him a tenant on the opposite side of the Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues site to the one he preferred. Thus O’Malley was bound and determined to keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn, even if it meant being the number one and controlling tenant in a municipally-owned stadium.

In addition to their Ebbets Field home schedule, the Dodgers played 15 games in Jersey City during the 1956 and 1957 seasons.

Copyright © Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.

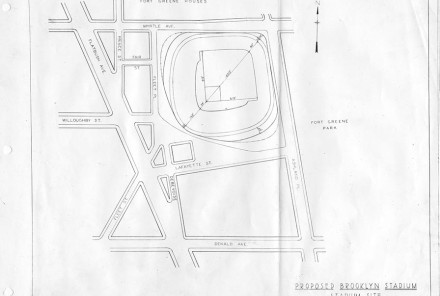

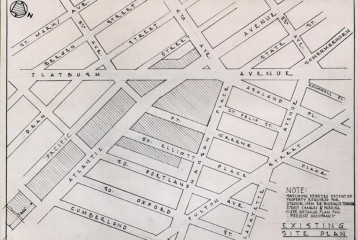

One of the main debates regarding the Dodgers’ new proposed stadium included the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues.

Walter O’Malley favored a proposed stadium site at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues.

Short of that, all other options would be explored.

More than 60 years after Walter O’Malley was prepared to privately build a domed stadium for the Dodgers at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues in Brooklyn, that location is still very much in the news. That’s largely because it was where Barclays Center was built and the NBA New York Nets play their home games.

To get the arena built and secure the Nets to play in Brooklyn, New York elected officials thought so highly of the location, that 1) they used eminent domain to acquire private property in “three upscale Brooklyn neighborhoods,” 2) “bundled that land with a rail yard that New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority sold to (Russian Mikhail) Prokhorov’s group for $100 million, despite having internally estimated its value at $214 million; and 3) spent “somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 million on infrastructure projects related to the construction of Barclays Center and arranged for about $400 million in tax exemptions for it.” https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/08/mikhail-prokhorov-brooklyn-nets-sale-elizabeth-warren.html

As O’Malley kept having doors close on the East Coast, they started opening on the West Coast, as officials in Los Angeles showed their sincere interest in bringing a major league team to the glitz and glamour of Hollywood. Only the Los Angeles Angels and the Hollywood Stars, both of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League (PCL), had performed for the local fans. But that was the minor leagues, not the majors. Los Angeles’ leaders, in the mid-1950s, viewed the city in big terms — more cars, more entertainment, more attractions to visit than anywhere. But, in their estimation, it would take a major league baseball team to really place the city on the sports map.

Despite the desire of the city to have a major league team, the voters felt otherwise when it came to using bonds to fund the building of a municipal baseball stadium, as on May 31, 1955, Los Angeles turned down such a ballot measure. The apathetic vote meant the proposition’s $4.5 million bond issue was sunk and lessened the chances of attracting a major league team. This was a significant vote, since it meant that if the Dodgers were the right team to relocate in Los Angeles, O’Malley would have to build his own ballpark and not have a municipally-owned stadium, as was available in San Francisco, where voters there had passed a $4.5 million bond proposition to fund construction of a ballpark. O’Malley saved the 1955 newspaper clipping on this important topic. Gladwin Hill, New York Times, June 2, 1955, “Los Angeles Vote Vetoes Ball Park” article

On August 17, 1955, O’Malley served notice to all that his intentions were serious, as the 1956 Dodgers would play seven “home” games, one game against each National League opponent, plus an initial exhibition game in Jersey City, New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium. It was a bold move by O’Malley, who worked out a lease for the ballpark, sending a message to the politicians that there was an urgency in getting a response to his quest for land and a final solution to the aging Ebbets Field problem. O’Malley would pay $50,000 to help upgrade Roosevelt Stadium (30,000 capacity and parking for 4,000 cars) for major league games. In the Dodger press release that day, O’Malley explained, “We plan to play almost all of our ‘home’ games at Ebbets Field in 1956 and 1957 but will have to have a new stadium shortly thereafter. Our present attendance studies show the need for greater parking. The public used to come to Ebbets Field by trolley cars, now they come by automobile. We can only park 700 cars. Our fans require a modern stadium — one with greater comforts, short walks, no posts, absolute protection from inclement weather, convenient rest rooms and a self selection first come, first served, method of buying tickets. Baseball, with its heavy night schedule is now competing with many attractions for the consumer’s dollar and it better spend some money if it expects to hold its fans. Racing has found a way to get State legislation and financing for a super-colossal proposed race track. I shudder to think of this future competition if we do not produce something modern for our fans. We will consider other locations only if we are finally unsuccessful in our ambition to build in Brooklyn.” Official Dodger Press Release, August 17, 1955

Brooklyn Dodgers at Roosevelt Stadium | ||

1956 | Record (6-1) | |

|---|---|---|

April 19 | W, 5-4 | Philadelphia Phillies |

May 16 | W, 5-3 | St. Louis Cardinals |

June 25 | W, 3-2 | Chicago Cubs |

July 25 | W, 2-1 | Cincinnati Reds |

July 31 | W, 3-2 | Milwaukee Braves |

Aug. 7 | W, 3-0 | Pittsburgh Pirates |

Aug. 15 | L, 1-0 | New York Giants |

1957 | Record (5-3) | |

April 22 | W, 5-1 | Milwaukee Braves |

May 3 | W, 6-0 | St. Louis Cardinals |

June 5 | W, 4-0 | Chicago Cubs |

June 10 | L, 3-1 | Milwaukee Braves |

July 12 | W, 3-1 | Cincinnati Reds |

Aug. 7 | L, 8-5 | New York Giants |

Aug. 16 | W, 4-1 | Pittsburgh Pirates |

Sept. 3 | L, 3-2 (12) | Philadelphia Phillies |

OVERALL RECORD: 11-4 | ||

Walter O’Malley meets with New York City officials regarding a new ballpark in Brooklyn for the Dodgers on Aug. 19, 1955. The meeting at Gracie Mansion included New York Mayor Robert Wagner (far left), Robert Moses, Parks Commissioner for the City of New York and Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore (far right).

AP Photo

On February 21, 1956, O’Malley issued a statement regarding a site survey of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues conducted by Brooklyn Borough President Cashmore: “Borough President John Cashmore, his survey committee and Mayor Bob Wagner have faced an important problem with courage and intelligence. The Dodgers, and for that matter all sports fans, are elated at the possibilities for a new stadium. We are also pleased this has the endorsement of Commissioner Bob Moses.

“Even without the Dodgers, this program is one of great Civic importance to New York City and the Borough of Brooklyn. Should the result be that a new stadium can be included at Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, the Dodgers would be interested in

a., buying the land, building and operating the stadium; or

b., participating in a bond issue; or

c., being a tenant.

It will be sad to see Ebbets Field demolished but anyone familiar with its many limitations will understand that this fine old landmark has to go and soon.”

While O’Malley did have support from leading businessmen in New York, as well as many newspapermen, he couldn’t get the numerous involved parties such as Moses, Stark, the Board of Estimate, Brooklyn Sports Center Authority and Borough Presidents, to come together. O’Malley’s internal memos, correspondence and historic documents suggest it was not for a lack of sincere effort on his part to find a workable solution in Brooklyn.

On April 21, 1956, Chapter 951 of the Laws of 1956 was enacted in New York. New York Governor Averell Harriman went to Brooklyn to sign the bill into law and vowed his support to O’Malley and the Dodgers.

“This law created the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority for the purpose of constructing and operating a sports center in the Borough of Brooklyn at a suitable location in an area bounded by DeKalb Avenue, Sterling Place, Bond Street and Vanderbilt Avenue, for the use of such amateur, professional and scholastic sports events as the Authority shall deem advisable and for the conduct of meetings, exhibitions and other events of civic, community and general public use. The Mayor implemented this law on the 24th day of July, 1956, by the appointment of Robert E. Blum and Chester A. Allen as members of the Authority and Charles J. Mylod as Chairman.” Interim Report of Brooklyn Sports Center Authority, November, 15, 1956 Blum was a Vice President of Abraham & Straus department store, while Allen was President of the Kings County Trust Company and Mylod, a lifelong Dodger fan, was President of Goelet Realty Company. None of the three was paid, but were to oversee the Authority’s issuance of $30,000,000 in its own tax-exempt bonds to carry out a four-phase civic improvement program, including a new 50,000-seat Dodger Stadium.

The respected Mylod stated, “Aside from the new ballpark, a great part of the Authority’s activity will lie in the solution of other problems. The old meat market has created an area not particularly adapted for residential use. The Long Island station is outmoded, so much so that the road’s newest equipment cannot enter that station. Thus service to Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan is not as satisfactory as it might be. The problem is to put an entire program together to improve this part of Brooklyn.” William R. Conklin, New York Times, September 12, 1956

The three-man committee of Mylod, Blum and Allen representing the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority was under funded and lacked the support of the Board of Estimate.

The same month, Moses wrote a proposed agenda for the Sports Center Authority outlining a three-year work schedule for detailed plans for the Meat Market, Railroad Terminal, land acquisition, street and arterial improvements and financing. He also endorsed the engineering firm of Madigan and Hyland to be employed “to report on the various sports to be accommodated in the Center the year round, the revenues which might be obtained, including, of course, the rental to be charged to the Dodgers for baseball and football, income from parking, food and other concessions.”

O’Malley wrote to committee member Mylod on July 31, 1956: “Bob Moses is all pepped up about the entire proposition. He has given Bob Blum a proposed agenda and time table for the Authority. Moses sees the entire matter completed in three years. This is ambitious but with his willingness to advise and consult and with his impetus and know-how, it could be. The Moses outline contemplates the hiring of engineers other than Clark [sic] and Rapuano. This is important as retention of Praeger, Kavanaugh [sic] and Waterbury would be desirable. Moses has selected the Praeger site in reference to the Clark [sic] and Rapuano site. This is a bit delicate as it will, no doubt, bring into focus the disagreement between Moses and (Brooklyn Borough President John) Cashmore. From our standpoint, either site would be highly satisfactory with preference in favor of the one Moses wants. The LIRR also wants this site.

“Bob Moses in his agenda outline calls for the employment of a hard boiled expert on the roof. I spoke to Captain Praeger about this and he feels from talks with Moses that a roof would be a terrific thing but Moses wants to be convinced as to its engineering and economic soundness. Praeger thinks that Ammon and Whitney, Port Authority Building, N.Y., are the best consultants on the roof. They, like Praeger, are thoroughly familiar with the latest large span enclosures and we feel that a report will show that the proposal is not only sound but economic.

“Another letter I think you should dispatch at your early convenience would be to Thomas Goodfellow, president of the LIRR. He has been completely overlooked by the Cashmore study group and I believe that was a serious mistake as there is a strong likelihood that the LIRR would take Authority bonds in lieu of cash for land which would be condemned. Goodfellow is a sincere executive...he has a real pressing problem and he would like to see daylight on it. None of his new air-conditioned equipment can come into Brooklyn at the present time because of track curvatures and platform limitations. This means that all that equipment goes into New York and the Long Island people who want to come to Brooklyn in new equipment could be critical of the railroad.” Walter O’Malley letter to Charles Mylod, July 31, 1956

While preliminary plans for the re-development project on a 110-city block area in downtown Brooklyn were underway, two possible sites were studied for the new Dodger stadium. O’Malley favored the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, while the other side supported the recommendation of an engineering report by Clarke and Rapuano, which preferred a site across the street, bounded by Flatbush Ave., Fourth Ave. and Prospect Pl. and got the nod from Brooklyn Borough President Cashmore. Charles G. Bennett, New York Times, July 25, 1956

Mechanix Illustrated in its July, 1956 issue said: “Subway and train connections emerge inside the building’s promenade. (The site of the dome will adjoin the Long Island Railroad’s Brooklyn Terminal.) The whole project is laid out to handle the maximum number of people safely and to facilitate the flow of vehicular traffic peaks that sports centers are bound to generate.”

On August 2, 1956, Moses wrote to Brooklyn businessman Charles Rickerson, “I am not a member of the Brooklyn Sports Authority, although I have on occasion been asked for advice. If my advice is followed, the only City capital money used will be for the purpose of moving the old meat market from its present location to Canarsie, eliminating an extremely bad vehicular traffic and parking situation, and providing some help in the construction of a new station for the Long Island Rail Road in return for railroad land so that the new improved air conditioned trains and modern freight cars can be accommodated. The Stadium itself will have to be self supporting. I don’t know in the absence of experts whether roofing over the Stadium is practical and economically feasible. It certainly might help to establish year round use and revenues.” Robert Moses letter to Charles Rickerson, August 2, 1956

O’Malley dealt with misstatement of facts, innuendo and outright lies in regards to his stadium proposal. For example, New York State Assemblyman John DiLeonardo wrote in a letter to O’Malley on September 8, 1956: “On behalf of the taxpayers of the City of New York, I ask that your organization turn down the invitation to occupy the Sports Stadium. The financial condition of the City of New York, as everyone knows, is such that it could not afford the loss of $5,000,000 in tax revenue. It is suggested that your organization concentrate on the plans for the expansion of the present ball park which were proposed a few years ago. Those plans called for enlarging your present stadium through the acquisition of title to an adjoining street and giving to the City of New York, sufficient land on other property held by your organization for replacing that street. May I suggest that you also give consideration to the proposal of the Queens Borough Chamber of Commerce for the construction by private capital of a stadium at the Sunnyside Railroad yards which has the best transit facilities in the City of New York and will also have ample parking areas.”