Feature

Dodger Planes Take Flight with Holman at Controls

By Brent Shyer

When youthful Harry R. “Bump” Holman landed the position of pilot for the Brooklyn Dodgers, he might not have known then that his career was just taking off.

Holman, who had grown up around airplanes, became the newly-assigned pilot for the Dodgers while attending college. His father Bud, a keen business leader in Vero Beach, Florida, was responsible for attracting the Dodgers there for Spring Training in 1948. As builder and manager of the local airport, Bud negotiated on behalf of the city with Dodger President Branch Rickey to establish the team’s training base called “Dodgertown.”

Rickey’s desire to travel to and from New York, as well as around the State of Florida, led to the Dodgers’ purchase of a Twin Beechcraft plane for his use.

“We had a pilot named Peter Gring then,” said Bump Holman. “He invited me to fly along as co-pilot when I was still in high school. That was the first actual Dodger airplane that I flew on. That was in 1948 or 1949. The Twin Beechcraft was just a small airplane (a five seater). Branch Rickey used that pretty much for himself.”

Plenty of development was still needed at Dodgertown when O’Malley became Dodger President in October 1950. He began to invest in and make many improvements on the site, which had been abandoned as a World War II U.S. Naval Air base, adjacent to the Vero Beach Airport. When the Dodgers first acquired the property once used to house the young fliers, weeds were sprouting to eye level at the spartan barracks. And they were just on the inside!

That same year, the Dodgers decided to find a larger airplane and this time a DC-3 was selected. How they acquired that plane may be part legend or the truth, as Holman explains.

Douglas DC-3 (1950-1956) In 1950, the Dodgers acquired a DC-3 from Eastern Air Lines President Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker. The DC-3 replaced the Twin Beechcraft that former Dodger President Branch Rickey used to fly around Florida and to and from New York to Vero Beach, Florida for Spring Training. Bud Holman is visible looking at the plane, standing on the far right.

“They were looking for something that Branch Rickey could have a bed in,” said Holman. “About that time, the airlines were beginning to get rid of their DC-3s and move up to a bigger airplane. Eastern (Air Lines) had 60 DC-3s. My Dad (who was Eastern’s representative at Vero Beach) said, ‘Let’s not buy one. I think I can probably just win one in a crap game.’ Down in Miami, he was with (Eastern President) Eddie Rickenbacker. A lot of stuff went on in Miami that I wasn’t party to. The word was that they rolled the dice, double or nothing, for a DC-3 down there and my Dad won it.

“They always swore it was true. I know they bought a couple of spare engines and paid a pretty good price for (them). That probably had something to do with it. That’s the word that my Dad claimed how they got their airplane. Dad turned around and gave it to the Dodgers.”

“I think the first time I met him (O’Malley) was in the Driftwood Hotel over on the beach,” said Holman. “My Dad was with him and we all went there for dinner. I was pretty young in those days. I was still in high school, back probably in 1947 or 1948. I can remember him making a remark that I was young, thin and skinny. He said, ‘He’ll make a pitcher when he grows up.’”

Holman was not destined to be on the mound, though he always admired Dodger star pitcher Sandy Koufax.

“I got interested in flying, just kind of grew up around it,” said Holman. “I soloed a plane the day before I was 16. I always flew around the airport here in Vero Beach,” said Holman, whose hobby turned into a career in the Dodger blue skies.

Initially, a series of pilots captained the Dodger DC-3 airplane with its designation of N1R on it and Holman served as co-pilot, even as he was attending Florida Southern College in Lakeland, some 100 miles from his hometown of Vero Beach.

“I was flying co-pilot with all of them,” said Holman. “A friend of my Dad’s and Eastern’s Chief Pilot named Frank Bennett finally told O’Malley, ‘Why don’t you let Bump fly the darn airplane. He flies it better than all these other guys we’ve had.’ I was still in college, so I couldn’t make all of the trips, but I could make a lot of them. I got all my training from these Eastern pilots. I used Eastern simulators in Flight School in Miami. They let me attend school and classes there in Miami.

“I believe it was sometime in 1953 when I flew my first trip as captain for them. I was still in college then. I majored in citrus, because we had citrus growing down here in Florida, and in business administration. I was really training to grow the citrus groves of my Dad’s. But, I love flying and I did that all my life. It just kind of got in my blood.”

It was the beginning of a long relationship for him as captain, not to be confused with Dodger Hall of Fame shortstop Pee Wee Reese, known to all as “The Captain.” For Holman, he still vividly recalls the excitement of piloting the Dodgers around Florida during Spring Training and eventually across the country.

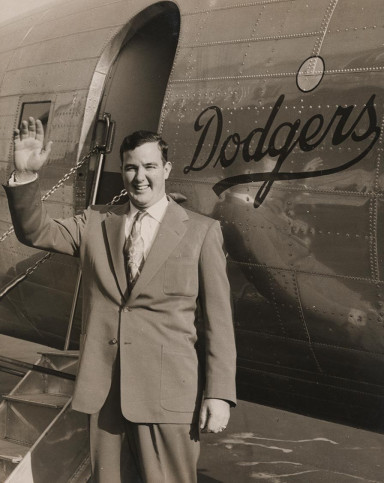

In front of the Dodger DC-3 airplane, Bump Holman prepares for a flight with the Dodger organization. Most of the time, Holman flew the Vero Beach, Florida-based plane around the state of Florida, taking the Dodgers to Spring Training games. But, in 1954, Dodger executives decided to experiment for a season by flying the minor league St. Paul, MN club on its road trips in the DC-3 with Holman at the controls. This continued for two more seasons, expanding to the Ft. Worth, TX minor league club before the major league Dodgers were flown in the new Convair 440 Metropolitan in 1957.

“I started flying captain, so I went to summer school, so I could get out in January and I could fly during Spring Training the whole year as captain,” said Holman. “We flew every day during Spring Training. We flew the club out of Vero to play around Florida. A lot of times, we made two trips because we only had 20 seats (in the DC-3). We’d go to Tampa and take the airplane over early and let some of the team off and come back and get the rest of them and go back over again. Then, after the game, it was two trips back and forth. We’d also go to New York two to three times a week during Spring Training (to pick up sponsors and VIPs).”

In 1952, O’Malley hired well-known engineer and Naval Captain Emil Praeger to design an intimate ballpark at Dodgertown. Praeger served as consulting engineer on the White House renovations in 1949. O’Malley and Capt. Praeger took time to work out every minute detail on an efficient, low-cost stadium with impeccable sightlines, in which the local fans could be close to the players and the game action. In the January 15, 1953 issue of the Vero Beach Press-Journal it was revealed that O’Malley had decided to name the stadium for the man who had done more than any other to assist in the early development of Dodgertown — Bud Holman.

Walter O’Malley and Bud Holman shake hands at the dedication ceremonies for Holman Stadium on March 11, 1953. Though he became a rabid Dodger fan, initially Holman knew little about baseball. As an astute businessman, he saw and acted on the opportunity to bring the Dodgers to Vero Beach for spring training. The plaque presented by the Dodgers reads, “The Brooklyn Dodgers Dedicate Holman Stadium to Honor Bud L. Holman of the Friendly City of Vero Beach, Walter F. O’Malley, President, Emil H. Praeger, C.E., Designer, 1953.”

Ceremonies were held for the opening of “Holman Stadium” on March 11, 1953 and O’Malley unveiled a plaque which read: “The Brooklyn Dodgers dedicate Holman Stadium to honor Bud L. Holman of the friendly City of Vero Beach.” An overflow crowd of 5,532 (in the new 5,000-seat stadium) attended an exhibition game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Philadelphia Athletics. Connie Mack, Philadelphia’s owner and Hall of Fame Manager was in attendance for the ceremonies, while Baseball Commissioner Ford C. Frick, National League President Warren C. Giles and American League President William Harridge were also present to celebrate the gala Grand Opening.

Bump Holman recalls the reaction of his family to the good news.

“It was a surprise,” said Holman. “My Mother knew about it. My Dad was the last one to know. She said, ‘Shhh, they’re going to name the stadium here after Dad.’ We were all excited about that. When he was told, Dad was very excited about it and was very proud.”

Initially, Bud Holman’s devotion to the sleepy-eyed Vero Beach community led to his pursuit of the Dodgers and their 26 minor league teams. As time passed, his interest grew in watching and enjoying baseball, especially the Dodgers. “He got to be a big fan,” said son Bump.

Holman explains that since most of the time the Dodger DC-3 airplane was parked and waiting to be flown following Spring Training, an experiment took place with a minor league affiliate which changed the course of history.

“After Spring Training, they hardly used the airplane during the ‘off-season,’ maybe once or twice,” said Holman. “In 1954, Dodger executives came to me and said pick one of these (minor league) ballclubs and go see if you can fly one for a season. See if the airplane is dependable enough, if we can overcome the weather problems and all the obstacles to see if we can fly a ballclub all year. So, we picked out the St. Paul (MN.) ballclub in the American Association. I flew them all that summer. We made all the games. We didn’t have any problems — no breakdowns, no mechanicals and no weather issues. So, the next year, they kind of branched out...we flew St. Paul all year and then they threw in the Ft. Worth (TX.) club. I flew St. Paul on every trip, but when they were staying at home, I’d run down and fly Ft. Worth and run them around for a couple of weeks. This was in 1954-56.”

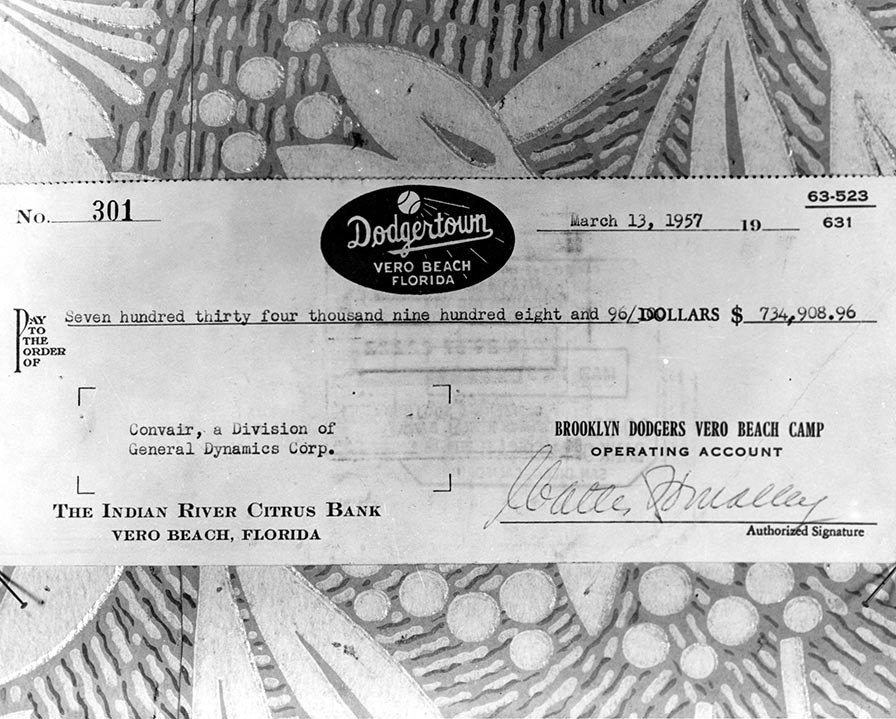

By then, the successful experiment complete, it was time for O’Malley and others to locate a larger airplane in which the Dodgers could travel on a regular season basis. The purchase of a twin-engine plane for more than $700,000 meant the Dodgers were the first team in baseball history to own their own airliner to transport the team.

Convair 440 Metropolitan (1957-1960) The Brooklyn Dodgers Convair 440 Metropolitan twin-engine plane was purchased on January 4, 1957. The Dodgers took delivery of the plane in mid-March. At the time of purchase, Dodger President Walter O’Malley announced to Associated Press, “This is the first time a major league club has bought an airplane.”

“In 1957, they bought a Convair 440, brand new right from the factory,” said Holman. “It was like double the airplane. Twice as much horsepower and twice the seats — it had 44 seats in it. Eastern ordered 20 of them and O’Malley and my Dad got wind of it. They waited until (Eddie) Rickenbacker was down at the Convair factory in San Diego and they went out there the same time he was there and said up your order to 21. It was identical to the Eastern airplanes with the same interior.

“The only thing we did to that airplane was put an automatic pilot in it. Eastern didn’t believe in auto pilots. Of course, they flew short trips, little 30 minute trips. We had long ones, so I finally talked them into letting me put an auto pilot in it.

“It was painted with the same Eastern duck hawk on the tail. But, where their’s said, ‘Fly Eastern Airlines’ ours said, ‘Brooklyn Dodgers’ on the side. Where the round duck hawk was on the nose on the Eastern paint job, they put a baseball on there.

The largest check, at the time, drawn on Indian River Citrus Bank in Vero Beach, Florida, for the Dodgers’ second plane, the Convair 440 Metropolitan in the amount of $734,908.96 on March 13, 1957.

“As soon as we switched to the Convair, we jumped over to the Dodgers and flew them exclusively. I flew them on that plane during the seasons of 1957 to 1960.”

One of Holman’s most memorable flights was piloting Dodger officials and select players from New York to Los Angeles on October 23, 1957.

Capt. Bump Holman shows off the Los Angeles Dodgers Convair 440 Metropolitan airplane in October 1957, just after the name was changed to reflect the club’s new home city. He had it painted in Vero Beach, Florida before piloting team executives and select players on their inaugural flight to Los Angeles on October 23, 1957. In 1959 alone, Holman made 295 flights in the Convair in which he transported the Dodgers and three of the minor league teams to their road trip destinations. Dodger President Walter O’Malley once said that “owning their own plane helped the Dodgers to win the 1959 pennant.”

“I flew them out to L.A. and I kind of surprised them,” Holman said. “I wasn’t supposed to know they were moving, but I did. I went up to New York from Vero Beach to the Eastern gate at LaGuardia to pick up Mr. O’Malley and all the directors and everybody. Of course, my Dad went from Vero. The day before I went up there, I got a sign painter to come out and we painted out ‘Brooklyn’ and put ‘Los Angeles’ on the Convair. When we arrived in L.A., those who greeted us were surprised, too, because here was the airplane that already said, ‘Los Angeles.’ They really hadn’t made the official announcement. My Dad had told me. That was my idea (when they landed in L.A. it said “Los Angeles Dodgers”).

“Of all days we decided to go to L.A., we had terrible head winds and we stopped in Oklahoma City for fuel. By the time we got to L.A. some of the bands and others had left. We were about two hours late. In the plane, everybody seemed to be jovial. As I remember, it was a fun flight.”

Several thousand cheering fans and officials were still on hand, despite the delay, to greet the arrival of the Dodger airplane.

However, Holman did not receive the plaudits of O’Malley or his father for the still wet paint on the side of the plane when it landed in Los Angeles, the Dodgers’ new home.

“My Dad and Walter were a little bit mad at me about putting that ‘Los Angeles’ on the side,” said Holman. “I think they hadn’t really signed any contracts at that time.”

Even an Associated Press story that night noted: “A smiling O’Malley stepped out of the door first. He was immediately recognized by the crowd and a great roar greeted him. The plane bore in giant letters: “Los Angeles Dodgers.” Associated Press story, October 23, 1957

The Dodger Convair 440 arrives in Los Angeles for the first time on October 23, 1957 carrying club executives and select players as the welcoming committee and fans are ready to greet the Dodgers to their new home. Bump Holman had “Los Angeles” painted on the plane in Vero Beach, Florida prior to traveling to New York to pick up the traveling contingent and flying to Los Angeles. The Dodgers arrived more than two hours late for the festivities due to strong headwinds which necessitated a fuel stop by Capt. Holman, but it did not put a damper on the celebration as the bands played and the big crowd properly welcomed the traveling party.

While the Dodgers did relocate in Los Angeles in time for the 1958 season, they scrambled for a playing field, finally agreeing to lease the football-friendly L.A. Memorial Coliseum as their temporary home. The Dodgers, adjusting to a new city and the vast Coliseum’s makeshift baseball dimensions (including a short 251 feet to left field with a 42-foot high screen), stumbled to the finish line in seventh place.

An oil leak caused quite a stir during a Dodger flight from Houston to Austin, Texas on April 8, 1958, as smoke started pouring out of a faulty engine. The concerned Dodger players did have some fun at the expense of pitcher Don Newcombe, who was already in hypnotic treatment for his fear of flying. Fellow pitcher Ed Roebuck asked Newcombe, “What did your hypnotist tell you to do when an engine starts smoking?” An apprehensive “Big Newk” replied, “He told me to just grin and bear it.” That is exactly what he and all 29 players aboard had to do until Capt. Holman landed the Convair without further incident. The club had to make alternate plans for their next exhibition game against Milwaukee by chartering a four-engine plane to fly to Dallas. Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1958

“With the Convair, that was the first engine failure we had,” said Holman. “With the DC-3, we never had a failure that I can remember. In the Convair, we went from Vero Beach and were headed to Austin. We were on the downwind and I had to shut one engine down. American Airlines was flying the other team that the Dodgers were playing and they were laying the pattern to land the same time we were. As soon as I got off our airplane, I asked, ‘Do you have anyone from the American charter department here?’ They did have someone on board. I said, ‘We need an airplane to get from here to Dallas as soon as the ballgame is over.’ They said, ‘Okay, we’ll see what we can do.’ American picked them up and flew the Dodgers to Dallas. Eastern flew another engine out to Austin for us, we changed it that night and we caught up with them the next day.”

Persistent rains forced cancellations of four consecutive games in Florida in mid-March of 1959. Through his numerous contacts, O’Malley arranged to have his plane head south. Holman recalls the hasty preparations to play the Cincinnati Reds in Cuba.

“I flew them down to Havana in the Convair,” said Holman. “It was after Castro had taken over, but they didn’t realize Castro was Communist then. I actually had to make two trips. The weather was so bad in Vero Beach, we needed to stop in Miami to pick up life rafts and vests at Eastern, but we couldn’t get a clearance down there. The weather was also bad in Miami and the traffic was so busy. I said, ‘Well, we’ve got to do something.’ We were sitting down at the end of the runway, with the engines running and everybody on board. We called Eastern in Tampa and asked if they had rafts and vests over there and they said sure. We could get a clearance from Vero to Tampa.

“The Eastern guys while we were there said, ‘Where are you going?’

“We said, ‘To Havana to play an exhibition game.’

“They said, ‘I don’t know who you are going to play because Cincinnati didn’t go.’

“‘What do you mean they didn’t go?’

“‘They were on one of Eastern’s flights going to Miami and then they were going to change planes in Miami, but they cancelled all the flights there.’

“They had the same problem we did. They turned around and went back to the hotel. I said, ‘Whoa. Wait a minute.’ I called and got Walter. He was on the airplane with my Dad and the rest of the team. So they ran in and called the Cincinnati club and said, ‘Hey we’ll send our airplane back to get you.’ They said, ‘Okay.’

“I went to Havana and dropped the Dodgers off, turned around, came back and got the Cincinnati club and took them down there. That was one of the advantages of having your own airplane.

“I’ll never forget after we arrived in Havana after the last flight,” said Holman. “The ballplayers were all gone and I got the airplane parked and put to bed. Here comes this limo about a block long. The chauffeur jumps out and goes around and opens the back door and this guy jumps out and he’s got gold braid all over him and medals.

“He introduces himself and says, ‘I am the chief of police of Havana and I’m going to watch your airplane for you while you are here.’ I thought — that’s nice, thank you sir. I notice all of a sudden, he sticks his hand out. I gave him twenty dollars and he said, ‘Oh no, I watch it a lot closer than that.’ Then we just put money in his hand until finally he says, “That’ll do.’ Then he gets back in his limo and away he went. I’m sure that’s the last time he ever saw our plane.”

Despite the soggy start in Spring Training, the Dodgers of 1959 had a fresh outlook with one trying season under their collective belts in Los Angeles. With the acquisition of outfielder Wally Moon and the call-up of nine-year minor leaguer Maury Wills to the lineup, the Dodgers were re-energized. They found themselves right where they wanted to be — in the World Series against the “Go-Go” Chicago White Sox. After playing in front of consecutive crowds of 92,000-plus at the Coliseum for Games 3-5, the Dodgers went back to Chicago for Game 6 and clinched the Series, four games to two. The final 9-3 win by Series MVP Larry Sherry of the Dodgers was the capper and gave them their first World Championship in their new hometown.

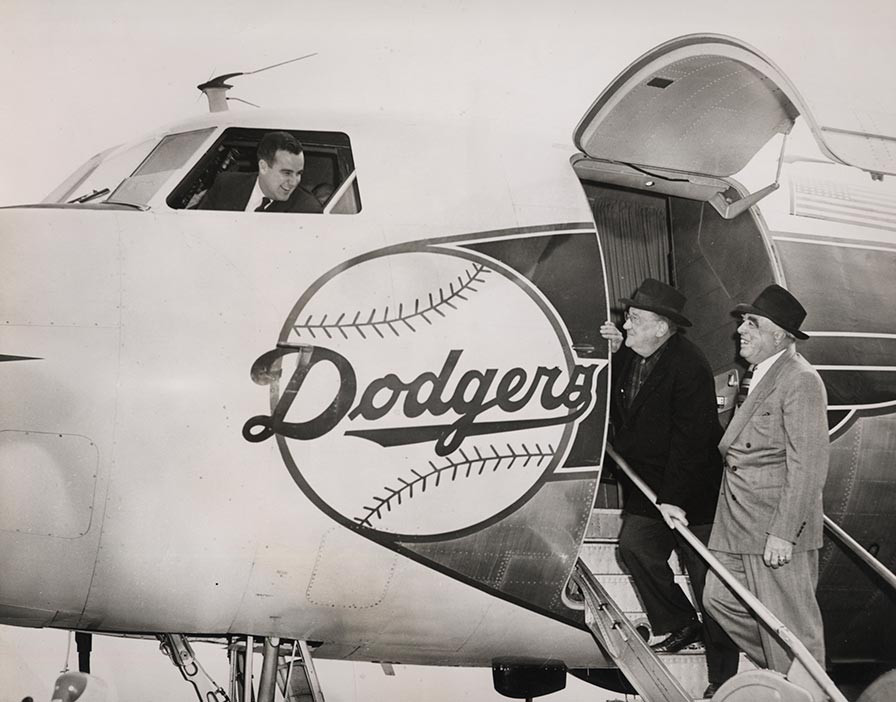

Dodger President Walter O’Malley and Dodger Director Bud Holman are on the steps of the 44-seat Dodger Convair 440 Metropolitan twin-engine plane. Holman’s son Bump is visible in the cockpit window. O’Malley added to the order of Eastern Air Lines to purchase the plane directly through the Convair factory, with the assistance of his friend Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, President of Eastern. Bud Holman served as a Director of the Dodgers and was Eastern’s representative at the Vero Beach Airport.

After celebrating at the Chicago Hilton Hotel the night of October 8, the Dodgers boarded a United Air Lines charter plane to let the real party begin before thousands of dignitaries and fans at L.A. International Airport. Desi Arnaz served as master of ceremonies for the welcoming reception and victory speeches.

“I’ll never forget that morning,” said Holman, who was at the controls of the Convair 440 carrying the Dodgers. “We stayed overnight after the last game was over. We were leaving in the middle of the morning the next day. You normally call ground control to taxi. I called them and said, ‘Chicago ground, this is the World Champion Los Angeles Dodgers, ready to taxi.” They came right back and said, “Dodgers, you can just sit there for a while!” The air traffic controllers were just venting some local frustration and having a little fun at the Dodgers’ expense. But, Holman has had his share of more difficult moments in the cockpit.

On March 20, 1960, the Dodger plane was forced to retrace its path to Vero Beach en route to Orlando and the players eventually had to travel by land. According to the Associated Press story, “Many of the Dodgers admitted being frightened when the motor of the chartered Convair suddenly started backfiring. Capt. Bump Holman, who has piloted the Dodgers hundreds of thousands of miles, feathered the propeller and assured his passengers that the plane could operate on one engine. There were some wisecracks and nervous laughs as the plane returned to Vero Beach. Manager Walter Alston, who had been up in the pilot’s cabin, walked into the passenger compartment and said: ‘Sorry I loused it up, fellas.’” Associated Press, March 20, 1960

O’Malley had some concerns about continuing to fly his precious cargo — the Dodgers — in the two-engine Convair 440, especially over the mountains across country. Basically, the Dodgers flew in the Convair for short hops in the Midwest and East, but chartered on United Air Lines for transcontinental trips.

Two days before Christmas in 1960, O’Malley summoned Holman from Vero Beach to Los Angeles to meet with him on the topic of upgrading to a bigger and better Dodger-owned airplane.

“O’Malley asked me, ‘What’s the best four-engine airplane to get?’” recalls Holman. “He and I had talked about an Electra for a while, but Lockheed refused to talk to us about it. They said, ‘You can’t support the maintenance for it — it’s too complicated an airplane.’ But they didn’t realize our connection with Eastern. Eastern had 60 of them at the time and they would support us. But, we couldn’t convince Lockheed of that. I said a DC-6B is the next choice. He said, ‘Get out of here and go buy the best DC-6B in the world. You have it delivered to Vero Beach and the crew trained by February 15 for Spring Training.’ He said, ‘I want four bunks in it and six card tables and anything else you want in the cockpit. Now go get it.’”

Douglas DC-6B (1961) A view of the Los Angeles Dodgers DC-6B airplane, which transported the Dodgers in the 1961 season. Capt. Bump Holman also piloted the Los Angeles Angels that season on their road trips using the Dodger Douglas DC-6B.

Now under orders from the boss, Holman immediately returned to Vero Beach and then the day after Christmas went to find a DC-6B plane in New York. He and a broker representing the Dodgers, who was trying to sell the Convair 440, looked at five DC-6B planes owned by Arabian American Oil Company, but decided to pass on them.

“In the meantime, SAS in Copenhagen had some nice sounding airplanes,” said Holman. “I talked to them on the phone and they said, ‘Okay, come on over here.’

“I said, ‘We don’t have any passports.’

“‘Where are you?’

“I said, ‘We’re in New York.’

“They said, ‘You be at the airport tomorrow morning at eight o’clock and we’ll have seats for you and your passports.’

“We drove out to the airport and they had the State Department there and made passports for us right there in the lobby of SAS. We flew to Copenhagen and picked out the plane we wanted, the kind of equipment we wanted, the seats, the color and all of that. They said, ‘You guys go to the hotel and be back here at one o’clock and we’ll give you the price. In the meantime, I had the broker traveling with us and he got an offer on the Convair from Aviaco in Spain.”

Holman quickly returned to Los Angeles to update O’Malley with the good news about the available DC-6B from SAS and the offer from Aviaco on the Convair.

“O’Malley said, ‘What have you got?’ I said, ‘We got the Convair sold and got a DC-6 out there lined up.’

“He said, ‘How much?’

“I said, ‘I got $700,000 for the Convair’ and he about fell out of his chair.

“He said, ‘What do we do?’

“I said, ‘The people from Spain are sitting right outside your office.’

“He said, ‘Well, bring them in here.’ So he trotted them in the office and they had a big, long contract and everything. O’Malley said, ‘Let me do the contract.’ He wrote about a three liner. ‘This is our agreement. This is it. Give me the check and here’s the deal. Done.’

“He said to me, ‘What about the DC-6?’

“‘Well, I have three people from SAS sitting outside the office.’

“‘Bring them in here.’ He said, ‘Now, we got the card tables and the bunks and the front end the way you want it?’ He just asked me a few questions about it.

“I said, ‘Yep.’

“He said, ‘How much?’

“I said, ‘$390,000 bucks’ He said that’s half of what we thought it was going to be.

“‘Same thing,’ he said, ‘Let me do the contract.’ He picked up his pen and he started writing his name on there and sat back in his chair and chomped on his cigar a minute. He said, ‘You know we’re buying a used DC-6B, because there aren’t any new ones. Why can’t we buy a used Electra?’

“I said, ‘I don’t know but I can find out in short order.’

“He said, ‘How short?’

“I said, ‘I’ll bet you in an hour or two.’ So he asked the SAS people, would you wait 24 hours for me to sign the contract?’ They said, ‘We’ll wait 24 hours.’”

The Dodgers became the first major league baseball team to own their own airplane, as they purchased a Convair 440 Metropolitan twin-engine. From left to right, Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, President of Eastern Air Lines, Dodger Director Bud Holman, Dodger President Walter O’Malley and Dodger Director James Mulvey show a model of the Convair 440. The Dodgers made the purchase of the airplane on January 4, 1957, piggybacking on Rickenbacker’s order of airplanes for Eastern.

As SAS representatives patiently waited for a response, Holman recalls reconnecting with his father’s friend Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s World War I ace fighter pilot and commercial aviation pioneer, to find out where to buy a used Electra.

“I called Eddie, who remembered me as just a kid, you know,” said Holman. “I’d met him on and off over the years. I said, ‘Do you want to sell one of your Electras?’

“‘No, but you ought to know where one is for sale,’ said Rickenbacker.

“My Dad was General Motors dealer for 44 years,” said Holman. “They had the test bed airplane — they had Allison engines in it made by General Motors — for sale. So, I said ‘Thank you.’ I called a friend at General Motors up in Detroit. I said, ‘Who do I talk to at Allison?’ He gave me the president of Allison, his personal phone. His secretary says he’s already gone for the day. She wouldn’t let me have the number. So, I called back to Detroit and I said, “He’s at a cocktail party and I can’t get him there.’ So, my friend said, ‘What’s your number? I’ll have him call you.’

“In about 10 minutes, the guy calls me back and I can hear the tinkling of glass in the background. I said, ‘We want to buy your airplane.’

“He said, ‘I can send a sales team out there to talk to you.’ I said, ‘No, we have to buy an airplane by noon time tomorrow.’ O’Malley is over there listening and says, “And tell him we’re not going to buy it without looking at it.’ I said, ‘We have to see it.’

“He said, ‘I don’t even know if it has engines in it! We take the engines in and out, you know.’

“I said, ‘Well, that’s the deal.’

“He says, ‘Who is this again?’

“So I told him. He said, ‘I’ll call you back in 30 minutes.’

“Boy, about 15 minutes later, he called back and said, ‘We’ll have the airplane in Burbank tomorrow morning at 11:45.’ We said, all right. We hung up and then Mrs. O’Malley and myself went up to Lake Arrowhead for the night and cooked out on the barbecue grill. We talked to this friend that we did have at Lockheed and we asked him to check on the airplane, because they keep records of everything they make, right down to the last rivet. He called us back that night and said, ‘You know, it’s going to take about $1.8 million to bring that airplane up to date.’ The new ones they still had out there I think were about $2.8 million. So we were kind of down in the dumps and thought, we’ll never buy that.

“We drove down to Burbank and got there about the same time the airplane did,” said Holman. “We walked inside.

“Walter said, ‘See what it’s got in the cockpit and see what we need.’ It didn’t have any interior in it. I said, ‘It needs a DME (Distance Measuring Equipment) and a transponder (which were just coming out then).’ He said, ‘What do they cost?’

“I said, ‘I don’t know.’

“O’Malley turned to this guy from General Motors and said, ‘How much does General Motors have this airplane on the books for?’

“The guys says a million six hundred thousand.’

“O’Malley says, ‘I’ll give your $1.8 million, delivered in Vero Beach on February 15.’

“The same deal, the crew trained and all that stuff.’

He said, “All of these, what do you call those things?’

“I said, ‘Service bulletins, A.D. notes, all these technical terms, you know.’

“He said, ‘All those things fixed and complied with.’

“The guy says, ‘Yeah, we’ll do that.’ They didn’t realize that they had to spend $1.8 million to get all those things done. The guy says, ‘We’ll accept that.’ He says, ‘Are you prepared to sign a contract with General Motors?’ ‘Yeah, we have one here.’

“O’Malley says, ‘Let’s go down to my office.’ He went down to his office and gave them one of those half-page jobs. They signed it and walked out the door. Then, we found out three days later, we couldn’t get one from them.

“They said, ‘You can’t have your airplane — we can’t get all these mods done and delivered to you until September 28, the last day of the baseball season.’

“Walter looked at me and said, ‘Now, what are we going to do? We don’t have an airplane! We sold the Convair yesterday.’

“In the meantime, we had already let the SAS people go that morning,” said Holman. “We said well we’ve made a deal, as soon as we sign the contract with General Motors. O’Malley said, ‘You better get those SAS people back here. I guess we’re going to have to buy that one to get by next year.’”

Panicking to beat the urgency of Spring Training, O’Malley and Holman had a brainstorm.

Holman said, “We don’t need one that fancy if we are only going to use it for a year. Western Airlines out here in Los Angeles has some very nice late model DC-6Bs. I said, ‘Why don’t we talk to them?’ O’Malley said, ‘Well, get out of here and go talk to them.’ I had a Volkswagen Bug I had rented for three dollars a day. I sail out to the (Los Angeles International) airport and walked into Western Airlines and I said, ‘Who do I talk to about buying an airplane?’ They said Mr. (Stan) Shatto is the guy in charge of selling airplanes. He later became president of Western Airlines and got to be a very good friend of Walter’s.

“I told him that we wanted to buy one and he said, ‘We’ve got 10 of them for sale.’

“I said, ‘I want the one with the lowest time since overhaul.’ I gave him the same deal — I want in it Vero by February 15 and the crew trained and all the same mods that we had talked about before.

“He said, ‘Okay, we can handle all that stuff.’

“I said, ‘How much?’

“‘$300,000.’

“I said, ‘Do you want to ride in my Volkswagen or do you have something a little bigger to ride in?’

“‘Well, where are we going?’

“I said, ‘I want to take you downtown and get you a check and introduce you to Walter O’Malley.’

“He said, ‘Really?’

“I said, ‘Let’s go!’

“‘Okay, we’ll go in my car.’ So we got in his Cadillac and drove down to the office and we had about a 30 minute conversation with O’Malley.

“Walter wrote up another one of those one-page deals,” said Holman. “At the bottom it states, ‘P.S. — If you can’t deliver by February 15, you will fly the team in Florida and in the season in a Lockheed Electra.’ They had about 15 of them. So, we said, okay that’s it.

Lockheed provided the Dodgers with a rendering of its new Electra II airplane, using the same colors as the Dodgers’ existing plane, the Convair 440 Metropolitan. Known as the “Kay O’”, the plane featured seating for 66 passengers and was used for Dodger travel between 1962-1970. The exterior was changed from the rendering to include blue speed lines.

“Wouldn’t you know, the mechanics at Western went on strike the next day? They had a heckuva time. They had all the executives out there doing the painting, changing the tires and putting the engines on. They had to bring another executive back in to do our training in the simulator. It was a vice president himself. It didn’t quite make it, so they ended up sending the Electra to Vero for about two weeks while they were finishing up our airplane. That’s how we got all those airplanes. It was the following year before we got the Electra. We had an extra airplane we didn’t need.”

Lockheed Electra II (1962-1970) A view of the Dodger Lockheed Electra II, dedicated “Kay O’” for Walter O’Malley’s wife Kay. O’Malley suggested the baseball and the speed lines to adorn the plane.

With the Electra II delivered in November 1961 in time for the 1962 season, Holman worked on the overall design of the interior and exterior features of that Dodger airplane, which would be christened “Kay O’” in recognition of Mrs. Walter O’Malley, First Lady of the ballclub. O’Malley was particular about the shape of baseballs on his plane. Holman need not have worried as he located a husband and wife interior design business in Ft. Worth, Texas named “Horton and Horton.”

“They were just delightful people,” said Holman. “I said, ‘Let’s design the paint job first. We want a baseball on the side that looks like a baseball.’ Walter always fussed. He said the baseballs never looked like one. It’s awfully hard to take a round sided airplane and paint a round baseball on it and have it look round when you look at it. You’ve got to paint it oblong to make it look round. We went back and forth and then Walter came up with the speed stripes that go from the baseball all the way back to the tail. That was strictly his idea. We sat there two days trying to figure out what to put on the tail. I think finally Mrs. (Dorothy) Horton came up with the idea of putting the skyline of L.A. back there. Then they started the interior and he left that up to me.

“O’Malley said, ‘I want four bunks in there and six card tables and a nice lounge area there. The rest is up to you.’

“We ended up with 66 seats,” said Holman. “Mrs. Horton was really a one-of-a-kind person. She said, ‘We have got to do something to really make this outstanding. I’m going to order the carpet.’ She spoke Spanish. She called to Brazil and ordered the carpet over the telephone. The carpet was 113 feet long and 15 feet wide, all in one piece. It was Dodger blue (royal blue) background and it had green baseballs and bats woven in it in a pattern. Bill Horton hired a guy who was a real painting artist. He painted that baseball on the plane, some 13 feet in diameter, while looking at a real baseball. It turned out to be a beautiful airplane and the ballplayers just loved it.”

The Electra’s exclusive baseball bat and ball carpet design is shown in color in this interior cabin photograph of the forward lounge and cockpit. Horton and Horton of Ft. Worth, Texas ordered the 113-foot long carpet (15-foot wide) in one piece from Brazil.

The interior galley of the Lockheed Electra II plane was used by the Dodgers to feed a hungry group of players and staff on their road trips.

One of six card tables in the cabin of the Dodger Lockheed Electra II that Dodger President Walter O’Malley requested for the players and coaching staff to use on board.

The $75,000 interior decorating job now completed at Meacham Field in Ft. Worth, it was time to fly the Electra II.

Holman enjoyed flying that plane best because it was completely self-contained. It had its own steps, a low baggage compartment for equipment and suitcases and its own built-in power supply, enabling it to run air conditioning while on the ground. Holman figures the Dodgers flew about 500 hours a year at about 400 miles per hour in the Electra II.

In its first year of transporting the Dodgers in 1962, the plane’s windshield broke in St. Louis on their departure date bound for Los Angeles. Traveling secretary Lee Scott had to scramble to get their hotel rooms back again and wait for the plane to be fixed. Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1962

“The ballplayers all loved their airplane,” said Holman. “They offered to put them on an airline flight to L.A. in an hour or two. They said, ‘No, we’ll just stay here. We’d rather wait and go on our own airplane.’ I had to take the airplane down to Tulsa to have a new windshield put in it. Then I came back the next morning and picked them up. I thought that was great that they thought so much of their own airplane that they’d wait over (a prolonged 21-hour delay from scheduled departure) rather than fly on a commercial jet.”

One incident with the plane that particularly stands out was on June 21, 1964, when, on a flight from Cincinnati to Milwaukee, the Electra II was jolted by a bolt of lightning.

Bob Hunter, Hall of Fame sportswriter of the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner , told UPI of the incident over Lake Michigan: “The ride began to get rough as we reached Lake Michigan and everyone was strapped into the seats. There had been several lightning sightings and then all of the sudden there was this glaring white light and the plane fell.” Hunter said there were some “nervous and pale” passengers but no one was ill. UPI, Chicago Daily Defender, June 23, 1964 Minimal damage (about $800) resulted to the Electra, though the bolt did strike the fiberglass radome (housing the radar antenna) on the nose of the aircraft. Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1964

Holman and the Electra II logged plenty of uneventful air miles, not only flying the Dodgers around the country but picking up and depositing many of their farm teams from Vero Beach. In April, 1964 alone, Holman flew 37,000 miles, the equivalent to 1 ½ times around the world. Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1964

In those early years of flying the DC-6B and the Electra II, the Dodgers worked out an agreement with the American League expansion Los Angeles Angels, whereby they too would use the plane for road trips. When the Dodgers were home, the Angels were on a road trip and vice versa.

“I very seldom stayed in L.A.,” said Holman. “I just unloaded the Dodgers and picked up the Angels and took them back East. For me, home was Vero Beach. The plane was housed in Vero. We flew every time they moved once the season got started, about every third day. We practically always flew at night after the game. During Spring Training, we flew every day...sometimes lots of trips. When we had the DC-3, I’d go to New York one day and come back the next. Then they got the Convair and I thought oh boy I’m going twice as fast. Then we got so I would go to New York back and forth the same day. Then we got the Electra II and we got so I would go to New York and back twice the same day. In Spring Training, they brought a lot of people to Vero. It was two and a half hours up and two and a half hours back to Vero. We could do that easy twice in one day.”

Holman and his co-pilot Dave White used to play a few good-natured tricks on unsuspecting players in the cockpit.

“We had one jump seat up there and we always let one player sit there,” said Holman. “They always took turns doing that. We always had a lot of fun with them in the Electra. It was a big, roomy cockpit, much bigger than the jets you see today. The flight engineer’s seat had a heckuva travel on it. That seat went up and down about three feet. Plus, it moved forward and back at an angle, to allow you to get by it.

“Some of the time, we would have the flight engineer get out of his seat, when the ballplayers would come up front and we’d say, ‘Hey sit in the flight engineer’s seat.’ We’d have it all the way up to the top and all the way back. They’d say, ‘Wow, this is something else.’ We’d say, ‘Slide the seat up here a little forward, so you get closer. Just pull that lever.’ We had intentionally told them the wrong lever. The seat would go down and it would fall about three feet. It scared them to death! They figured they were going to go right out the bottom!”

Dodger President O’Malley was a regular visitor in the cockpit of his team airplane, although Holman recalls the boss preferred sitting at the tables in the back.

“He used to come up there,” said Holman. “He loved to shoot the breeze with us. Most of the time when he was in the plane, he’d have my Dad or most of the other guys playing gin rummy. He didn’t get out of his seat too often.”

Los Angeles Angels owner and famed singing cowboy Gene Autry also made appearances in the cockpit. He not only sat with Holman, but took control of the Electra II.

“He used to come up to sit in the cockpit and I’d let him fly some,” said Holman. “Gene Autry was a pilot in World War II (for the Army Air Forces). He was a pretty good pilot, a little rusty, but a pretty good pilot.

“When we got the airplane from General Motors, they assigned Art Sunderland as the flight engineer. He started the first one of those engines of which Allison was really proud. Of course, when they had it, it didn’t have any interior or anything. It was just a test bed for them. When we got it, they assigned him to us, just being nice. They wanted to get good service out of the engines, and all that. Boy, when he saw that airplane with that interior, that was his baby. He was around there dusting it and wiping the fingerprints off. He treated it like it was his own.

“One night we came into L.A. about nine o’clock. It was a quick turn, as we were bringing the Angels out. We were cleaning the airplane out inside, dumping the ashtrays and sweeping up, the whole crew including this old fellow. We’re all working like crazy trying to get it straightened up.

“Here comes Gene Autry’s chauffeur and he’s got this damn saddle, a beautiful saddle with silver inlays all over it and everything.

“He says, ‘This is Gene Autry’s saddle and he doesn’t want to put it in the baggage department. He’d like to leave it in here somewhere so it doesn’t get scratched up. Where can we put it?’

“I said, ‘Bring it here and we’ll put it in the bottom of the coat closet.’ It was all carpeted and nice and I said, ‘It will be good in here.’

“I’m walking down the aisle in a suit with this saddle and this old guy from G.M. says, ‘What the hell is that?’ and I said, ‘That’s Gene Autry’s saddle. He’s going on this trip.’ I said, ‘He’s putting on an exhibition back east when he gets back there.’

“Anyway, he kind of looked at me funny and I said, ‘Now, you’ll have to close up the big table in the lounge back there because we’re going to put his horse back there.’ I thought this guy was going to die! ‘I’ll be damned if they’re putting a horse on my airplane!’

“We had a lot of fun with things like that.”

On one occasion, O’Malley’s wife Kay hitched a ride in the plane with the Angels to New York.

(L-R): Harry “Bump” Holman, Dodger pilot; Paul Loux, Dodger co-pilot and flight instructor. Capt. Holman and co-pilot Loux are in the cockpit of the Dodger-owned Convair 440 Metropolitan preparing for another flight.

“We were about half way between St. Louis and Kansas City and all of a sudden we notice the oil gauge on Engine #2 showing oil is going out,” said Holman. “So I sent flight engineer Paul Loux to go back and look at that engine. He runs out back to look. In the meantime, I saw the oil temperature going up, so we shut that engine down. We just kept right on going to New York. We told air traffic control that we were ahead of schedule, so we slowed down. I went back and talked to Mrs. O’Malley and she was right alongside of that engine. Her seat was right there. She always liked that seat beside the bulkhead. I said, ‘Hey, I’m sorry about that engine being shut down. I hope it didn’t scare you.’

“She said, ‘Oh, no, I like it this way, it’s a lot quieter.’”

Holman flew the Electra II through the 1964 season, when he retired to take over his father’s interests in Vero Beach. Dodger Director Bud Holman, who helped establish the Vero Beach airport in 1929, passed away on May 31, 1964. The elder Holman was a longtime citrus grower, Cadillac dealer and admired 41-year Vero Beach resident.

Dodger team pilot Lew Carlisle (left) stands with his wife Millie, who served as a flight attendant for Dodger trips around the National League. Capt. Carlisle is pointing to the flags of the international destinations to which the Dodger-owned Lockheed L-188 Electra II (named “Kay O’”) have also been.

“After my Dad passed away, I retired to run the businesses here in Vero,” said Holman. “I hired an ex-Eastern (Air Lines) pilot Lew Carlisle (as the new Dodger pilot). He had a ranch up in Idaho, so they moved the airplane west, closer to him. They kept it in Las Vegas. They were looking for a dry climate and that was a good safe place for it. I think it worked out pretty good for them.

Dodger pilot Lewis Carlisle (in suit) with the 1971 Los Angeles Dodgers and their 720-B jet plane named the “Kay O’ II”.

“I think they went overboard when they bought the next Dodger airplane, the 720-B Fan Jet (in 1970),” said Holman. “The reason I say that, it was a little faster airplane and it was a little bit roomier, but it was not a self-contained airplane. It didn’t have any steps in it and it didn’t have a ground starting unit — you couldn’t start it without outside assist. You had to have conveyer belts to load and unload it. So, I just thought it wasn’t a practical airplane for the Dodgers. Walter was really proud of it. He told me one day, ‘I don’t really need an airplane but I sure do like to ride to the airport here in Vero and say that’s mine.’”

After retiring from the Dodger pilot position, Holman continued to run his father’s Vero Beach Airport Services business which provided hangar and fuel. In 1980, he and his brother Tom bought Sun Aviation in Vero Beach, which handles aircraft maintenance and charters, including one jet and three turbo prop planes. Today, Sun Aviation has more than 50 employees and also handles flight training programs.

As to his remembrances of his years as pilot with the Dodgers, Holman said, “The time in the air was the pleasant part of it. I still have a piece of that baseball carpet from the Electra. I got along with just about everybody. We treated the team pretty well — like the Dodger organization, one big family.”

So, how did Holman get his nickname?

“I was a little baby, I had a kiddie car and I kept bumping into things and my older brother kept saying, ‘Bump, bump.’ Nothing to do with my flying — though I have been accused of it many times!”