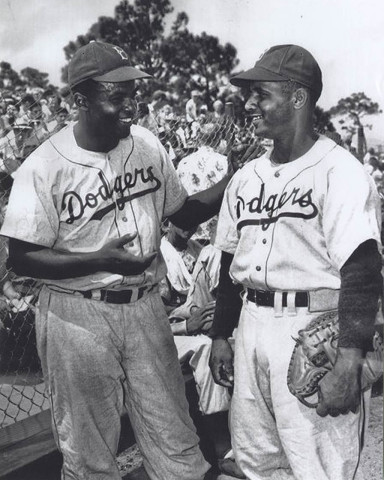

(L-R) Roy Campanella; Don Newcombe; Dan Bankhead; Jackie Robinson. Four record setting African-American Dodgers are at Dodgertown in the early 1950s. Roy Campanella won three National League Most Valuable Player Awards and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1969. Don Newcombe was the then only player in major league history to win the Rookie of the Year, the Cy Young Award and the National League Most Valuable Player Award. Dan Bankhead was the first African-American pitcher to appear in a major league game and hit a home run in his first at bat. Jackie Robinson won the first National League Rookie of the Year in 1947, the Most Valuable Player Award in 1949 and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

Photo by Peter O’Malley. All Rights Reserved.

Feature

“Haven of Tolerance” Dodgertown and the Integration of Major League Baseball Spring Training

By Jerald Podair

If you were an African American and lived in most parts of the American South in 1948, you could not do the following things with whites: Go to school with them. Eat in restaurants with them. Stay in hotels with them. Sit next to them in theatres and on buses. Drink out of water fountains with them. Go to the bathroom with them. Play golf with them. Live in the same neighborhood with them. The reason, of course, was the entrenched system of racial separation known as "Jim Crow," which had defined social and political life in the South for three-quarters of a century. But things were about to change in one part of the region, thanks to a Major League Baseball team that had already made civil rights history by bringing Jackie Robinson to the big leagues: the Brooklyn Dodgers. Seeking a permanent spring training home, the team leased an abandoned World War II Naval Air Station from the east coast Florida town of Vero Beach, and rechristened it "Dodgertown." Beginning in 1948, and for six decades thereafter, Dodgertown would serve as a "college of baseball" for the entire organization, imparting what became known as the "Dodger Way" to generations of young prospects, some of whom would go on to populate All-Star teams, capture pennants and World Championships, and in a few instances enter the Baseball Hall of Fame.

1948 Dodgertown employees raise a welcoming banner to everyone who is staying on the Dodgertown base in Vero Beach, Florida for Spring Training. The banner concept remained a Dodgertown tradition for players for the next 60 seasons. In 1948, it marked the first integrated Spring Training Camp for baseball in the South where all players, regardless of color, shared the same dining and living accommodations.

But Dodgertown was more than just an incubator of talent. Its significance extends beyond the playing field into the social and racial history of Florida, the South, and America as a whole. By offering an integrated and egalitarian workplace, one in which players were judged not by who they were but what they did, Dodgertown was unique not just among Southern spring training facilities, but among Southern institutions generally. Between 1948 and the early 1960s, one of the most virulent phases of the Jim Crow era, it stood, in the words of historian Jules Tygiel, as a "haven of tolerance," one of the very few racially integrated institutions of any kind in the state and region. Jules Tygiel, Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy: (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 317 At a time when African Americans could put their lives in danger by attempting to eat, drink, play, travel, or live with or among whites, Dodgertown stood as an example of interracialism that rebuked those who counseled caution, patience, and delay. Legendary sports columnist Sam Lacy wrote in the Baltimore Afro-American in 1974, "It was, without doubt, the first crack in the wall of prejudice that continued to plague baseball for the next 15 years." Sam Lacy, Baltimore Afro-American, Week of April 23-27, 1974 Like the story of Jackie Robinson to which it connects, Dodgertown represents a milestone in American civil rights history.

(L-R) Jackie Robinson; Roy Campanella. Jackie Robinson offers a congratulatory handshake to catcher Roy Campanella, March 31, 1948. The Brooklyn Dodgers have acquired Campanella from their Montreal AAA minor league team to add him to the Dodgers’ major league roster. On this date, the game is the first to be played by the Brooklyn Dodgers in Vero Beach at Dodgertown, the first racially integrated Spring Training camp in the South.

As has often been the case in our national history, Dodgertown’s advances toward racial justice were the products of both pragmatism and principle. Dodger management wished to build a team-controlled complex in which player development would be free from outside interference. It also needed to buffer the team's growing complement of African American players - which in 1948 included Robinson, pitcher Dan Bankhead and prospects Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe - against a hostile Southern racial environment. The lease of the former Naval Air Station from Vero Beach and the creation of a town-within-a-town permitted the team to realize both goals. See Jonathan I. Leib, "Major League Baseball's Spring Training in Florida, 1901-2001," The Florida Geographer, 32 (2001), 15 Dodgertown’s decidedly downscale facilities worked to foster camaraderie, friendship, and cohesion among the Dodger players who, regardless of race, lived in barracks left over from the war that lacked heat and air conditioning and featured primitive sanitary facilities. They ate communally, chow-line style, with stars and scrubs sitting side by side. See Thomas C. Schelling, Micromotives and Macrobehavior (New York: Norton, 2006), 143. The shared inconveniences bonded black and white players, molding individuals into a team for the demanding regular season that lay ahead. "It brought the team together, there’s no question about that," recalled former Dodger President Peter O’Malley, "and at the most important time of the year." See Charles Fountain, "Dodgertown Sits Eerily Quiet, " February 24, 2009 www.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/extras/extra_bases/2009/02/oh_the_metaphor.html

An aerial view of the Dodgertown barracks in Vero Beach, Florida. The integrated barracks and dining room of Dodgertown are located in the buildings toward the center of the photos and Dodgertown Field No. 1 is located just west of the buildings.

In 1948, Dodgertown inaugurated an experiment in interracial living that was almost unique in the South. Dodgertown’s barracks which under U.S. military policy, had been segregated during World War II, were now open to blacks and whites for the first time. This was made possible by the unique terms of the Dodgers' deal with Vero Beach officials. It was brokered by local auto dealer Bud Holman, who had helped build the Vero Beach airport; under his auspices the town of 3,600 had become Eastern Airlines' smallest regularly scheduled point of service. Wayne Brew, "Boom and Bust: Landscapes of Economic and Cultural Tradition," PAST Journal, 34 (2011) Holman hoped that the potential "Vero Beach" bylines for stories filed by New York sportswriters from a Dodger training camp would raise the town’s profile, and lobbied strenuously for it to become the team's new spring home. Ibid, 8-9, William Nack, "Dodgertown," Sports Illustrated, March 14, 1983 His efforts paid off. The Dodgers and Vero Beach reached an agreement under which the team would control activities within the complex's gates. This meant that while the facility would be in Vero Beach, it would not be of it, and Jim Crow restrictions on black activity would not apply within its boundaries. Local ordinances prohibiting integrated housing would be tacitly ignored, in a bit of civil disobedience that benefited both team and town.

This part of the Dodgertown agreement was not put into writing. It was more in the way of an unstated understanding that since the Dodgers would administer their own facility, they would enforce their own rules on the property. Sam Lacy, "A Fellow-Scribe Triggers Flashback," Baltimore Afro-American, April 23-27, 1974, 9 The Vero Beach authorities would adopt a "live and let live" policy toward Dodgertown activities, entering only at the team's request, with one exception: if exhibition games were played at Dodgertown for which admission was charged, separate accommodations for white and black spectators would be provided. This meant designated bathrooms, water fountains, entrances, and seating areas for black fans. Larry Still, "Militant New Stars Attempting to Bat Bias Out of Ball Parks," Jet, 19 (1961), 54-55. Even this requirement was not as onerous as some enforced in other Florida towns, which prohibited interracial athletic contests altogether; in 1946, police in Sanford had entered the field during an exhibition contest involving Jackie Robinson and ejected him and another black player from the ballpark. Jules Tygiel, Baseball's Great Experiment, 109-10

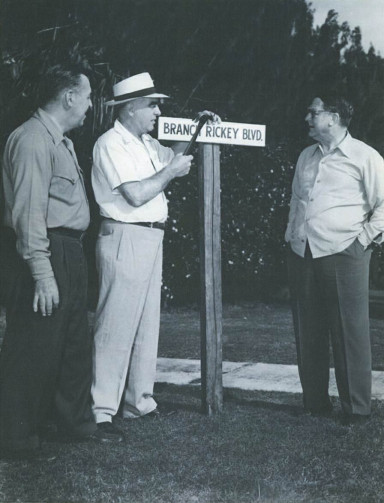

(L-R) Dodgertown Director Spencer Harris; Vero Beach business leader Bud Holman; Branch Rickey. A Dodgertown tradition is to name a street after a Dodger player or person has been named to the Hall of Fame. Here, Bud Holman, prominent Vero Beach business leader for whom Holman Stadium was later named, adds the final touches to a street sign “Branch Rickey Boulevard” for the current Dodger President in 1948, the first season for Dodgertown. Rickey was later elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967.

But while Vero Beach did not abide by such drastic policies, it was still a place where the racial mores of the Jim Crow South were observed. Encounters between black Dodger players and white Vero Beach residents were bound to be fraught with tension at best and at worst invoke the weight of the Southern justice system. It was thus all the more imperative to offer African American players not only equal accommodations at Dodgertown, but also a sense of inclusion and respect.

This is what Dodgertown provided, first under co-owner and general manager Branch Rickey between 1948 and 1950, and thereafter Walter and his son Peter O’Malley, who owned the team from 1950 to 1998. The 220 acres of Dodgertown, in fact, may have been the largest fully integrated area in Florida during the late 1940s and 1950s. With every other Florida spring training camp residentially segregated - African Americans were customarily barred from whites-only "headquarters" hotels and often forced to find lodging in black-owned private homes - Dodgertown was ahead of its time. See "Spring Camp Segregation: Baseball's Festering Sore," New York Times, February 19, 1961, 1, 3 It represented the first step toward integrating baseball's preseason, a move that was as significant as the integration of the game’s regular season in 1947.

It did not always go smoothly. In 1948, Dodgertown’s very first year, an argument erupted between African American pitcher Don Newcombe and a white Philadelphia Athletics catcher after an exhibition game, prompting spectators to threaten the Dodger prospect; one fan brandished a plank from a picket fence as a weapon. Nack, "Dodgertown" Branch Rickey, fearing further trouble, had the team's black players remain inside Dodgertown for the duration of spring training. From that time forward, Rickey and then the O’Malleys sought to offer African American Dodgers as many services as possible at Dodgertown itself, both in the spirit of fostering racial equality and as a practical matter, so as to conduct spring training productively and without distractions. The claims of justice and commerce thus intersected to move history forward.

The Dodgertown dining room at the Spring Training base in Vero Beach, Florida. From the first season in 1948, the Dodgertown dining room and their living quarters were desegregated for all players and personnel, an important and vital aspect of Dodgertown.

Until 1972, Dodgertown featured open, army-style barracks that were by their very nature desegregated. All other Dodgertown facilities with the exception of the team's locally-regulated playing field - which beginning in 1953 was Holman Stadium - were integrated. These included the dining hall, where the custom was for players to take open chairs at tables after getting their food, insuring integrated meal seating through random selection. There was no segregation on the playing field itself, of course, and the Dodgers became pioneers in the development of African American players. Robinson and even Campanella and Newcombe were only the leading edges of a flow of talent that would culminate on the major league level when in 1954 they became the first team to field a majority-minority starting lineup (including Robinson, Newcombe, Campanella, second baseman Jim Gilliam, and left fielder Sandy Amoros).

Walter O’Malley tried to blunt the impact of segregation in Vero Beach by providing recreational facilities at Dodgertown, including a swimming pool built in 1949. He installed a movie theatre, a game room, and stocked a pond with bass for fishing. Ibid. In the 1950s, Dodger management sought to persuade Vero Beach businesses to accept black patronage, with mixed results. Timothy M. Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams," Boston Globe, March 17, 2008 As a way of emphasizing the team's impact on the local economy, it had 20,000 $2 bills stamped with the words, "Brooklyn Dodgers" and given to players to spend in town. Mark Langill, Dodgertown (Charles, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 8; See also Rep. Bill Posey, "Florida's 15th District" Since Vero Beach merchants would undoubtedly see how the loss of the Dodgers would affect their bottom lines, Walter O’Malley hoped they would respond more positively to African American customers. O’Malley coupled this indirect pressure with a more explicit demand for equal treatment in Vero Beach's business district. Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams"

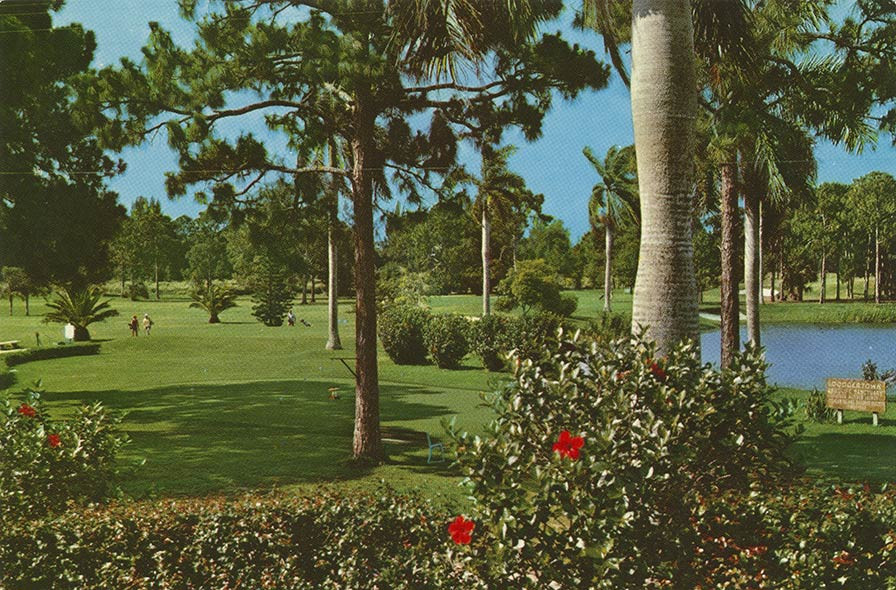

A postcard of the nine-hole golf course and wildlife sanctuary at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida. Walter O’Malley had opened a makeshift pitch-and-putt course in 1954 and added a nine-hole golf course in 1965, so all players could enjoy a relaxing game as the two local existing golf courses were segregated.

But throughout the 1950s, "bars, beaches, golf courses, some restaurants, and the town’s better stores remained off-limits." Brew, "Boom and Bust." It would, in fact, not be until the mid-1960s that Vero Beach's stores and theatres served African Americans. Nack, "Dodgertown" As late as 1971, black outfielder Willie Crawford was turned away at a local bar. Ross Newhan, "Poised Crawford Suffers Racial Snub, Keeps His Cool," Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1971 O’Malley flirted with the idea of moving his spring training site to the West Coast, where these issues would not exist, but had invested too deeply in Dodgertown - both financially and emotionally - to pull away from it. Letter, Walter O’Malley to Frank Scott and Robert C. Cannon, August 8, 1961 Unable to control over what lay outside Dodgertown, he sought to make what lay within its boundaries open and equitable.

Walter O’Malley’s goal during spring training at Dodgertown was to bring the team and organization together. He emphasized communal activities - St. Patrick's Day parties, memorial masses for Dodger personnel who had passed away during the preceding year, recreation rooms with ping pong and pool, movie nights, family activities, and beginning in 1954, golf. That year, O’Malley opened a pitch-and-putt golf course at Dodgertown, in part to address his own growing interest in the sport, but also to give African American Dodgers a place to play, since the local Riomar and Vero Beach country clubs were open only to whites. In 1965, with African Americans still barred from Vero Beach courses, Walter O’Malley built a 9-hole course at Dodgertown; he added an 18-hole course in 1971. Peter Kerasotis, "Dodger Blues," Golf Journal, March-April 2002; Charles Fountain, Under the March Sun: The Story of Spring Training (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 72; Nack, "Dodgertown"; Joe McDonnell, "If Roy Campanella Didn't Invent Courage, Who Did?," Sepia, September, 1980, 74; Ross Newhan, "Not Everyone Was a Happy Camper," Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2008, D6

Peter O’Malley recalled that "the real reason (his father) built the nine-hole course was so the black ballplayers could have a place to play." Kerasotis, "Dodger Blues." According to African American Dodger outfielder Lou Johnson, "When they put that golf course up there, that was a highlight. I didn't know one place we could go to play golf. That made a big difference, I think, in the African American players in their appreciation of Walter O’Malley." Fountain, Under the March Sun, 72. O’Malley’s concern extended beyond the golf course to more everyday matters. When Johnson was refused service at a Vero Beach laundromat in 1965, O’Malley arranged for on-site washing and drying facilities at Dodgertown. Nack, "Dodgertown"; Jim Murray, "Color It Zero," Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1965, B1

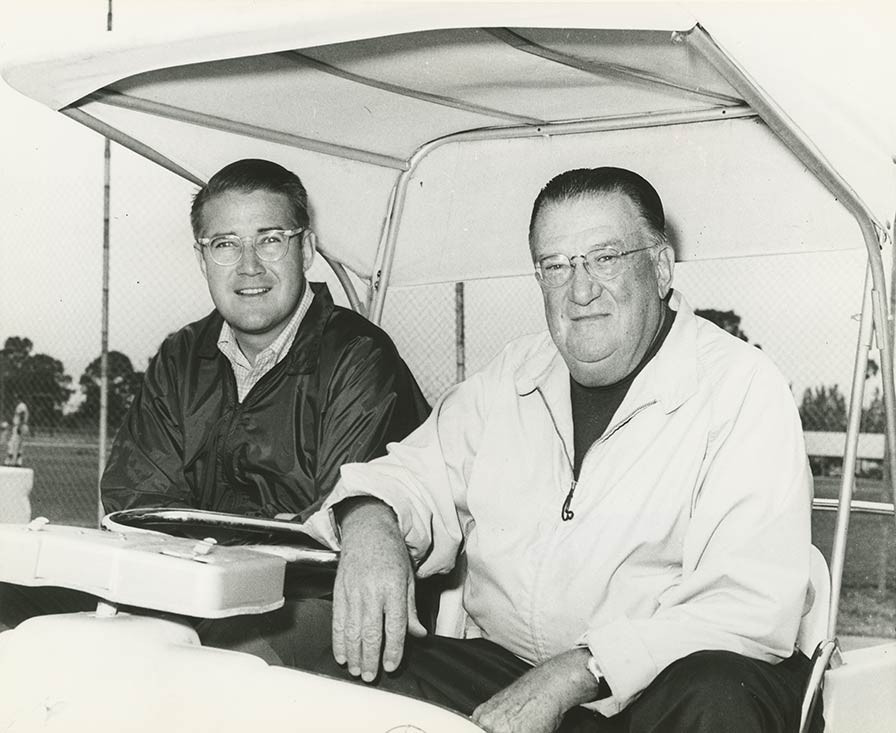

(L-R) Peter O’Malley, the President of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Walter O’Malley, the Chairman of the Board of the Dodgers, are in Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida. Walter O’Malley was one of four Dodger equal stockholders when Dodgertown opened in 1948. The O’Malley family continued to develop and modernize Dodgertown, including new accommodations, clubhouse, lounge and two golf courses. In 1962, Peter O’Malley was the Dodgertown Camp Director who integrated Holman Stadium for all fans.

But while the O’Malleys did what they could to spare their black players the indignities of Jim Crow, it was obviously no substitute for the end of the practice altogether. By the early 1960s, with the modern civil rights movement sweeping through the South, the racial atmosphere was changing. Two organizations that had not existed when Dodgertown opened its doors in 1948, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr's Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had employed the tactics of nonviolent direct action - targeted civil disobedience - to attack Jim Crow at its grassroots. Just as important as these new tactics of the civil rights movement were the changes underway in the racial culture of the South. World War II and its aftermath had put an end to a period of Southern economic stagnation and isolation that had lasted for three-quarters of a century. Attracted by low taxes and labor costs, Northern businesses were relocating to the "Sun Belt" and the region was attracting increasing interest from investment and financial institutions. By the early 1960s, buoyed by an influx of businesses and residents from other parts of the country, the South was no longer the nation’s economic backwater.

Nowhere was this more evident than in Florida itself, which was diversifying from its traditional economic bases in agriculture and tourism to aerospace, defense, manufacturing, construction, and finance, all of which drew employees from outside the South and aligned the state more closely with national politics and culture. By the early 1960s what had seemed impossible only a few years before - the integration of spring training stadium seating and residential accommodations - was bubbling just beneath the surface of Florida's social structure. The O’Malleys had long chafed under the obligation to segregate spectators at Holman Stadium, but felt they had no choice but to abide by the local ordinance requiring the races to be separated at public events where admission was charged. Still, "Militant New Stars Attempting to Bat Bias Out of Ballparks," 54-55 At Dodgertown’s first exhibition game in 1948, Vero Beach police had required black fans to move three times to maintain their distance from whites. Wendell Smith, "Roy Looks Classy as Newest Dodger; Jackie Hits Homer," Pittsburgh Courier, March 31, 1948

An aerial color view of Dodger players at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida, reminiscent of the LIFE magazine cover of minor league Dodger players in 1948. Don Newcombe, who was the first major league player ever to win the Rookie of the Year, the Most Valuable Player Award and the Cy Young Award, stands on the far left in the first row at the front. Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in the major leagues in the modern era, stands on the far left in the third row. Fresco Thompson, the Dodgers’ minor league director, stands on the far right wearing a white Brooklyn hat.

But their opportunity to challenge this policy came in 1962, thanks in part to the work of a biracial committee formed by residents of Vero Beach and nearby all-black Gifford which sought to make the transition to integrated institutions less volatile and confrontational than it had been in other parts of the South. Tom Moczydlowski, "Segregation Outlived Robinson Era," Vero Beach Press-Journal and Sunday Free Press, February 21, 1988, 27 In early 1962, members of this committee met with Peter O’Malley, who had recently become the director of Dodgertown, to discuss the possibility of desegregating Holman Stadium. One of the committee members, Ralph Lundy, recalled that "he (O’Malley) was very receptive and understood the problem. He knew what we were asking." Ibid. African American Dodger stars Tommy and Willie Davis had also spoken to O’Malley on the same issue as spring training began. Dom Amore, "Sad Prospects at Vero Beach," Hartford Courant, March 16, 2008; Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams" A few months earlier, Walter O’Malley had written to the Major League Baseball Players Association expressing his frustration with legally mandated segregation at Holman Stadium. "There are local city (of Vero Beach) ordinances," he complained, "that are not in keeping with our thinking which, however, cover situations off our self-contained base. Our relations with the local political administration are not cordial at the moment and we have been giving some thought to transferring our base to the West Coast unless we see signs of improvement." Letter, Walter O’Malley to Frank Scott and Robert C. Cannon, August 8, 1961

The Dodgers' move from New York to Los Angeles in 1957 had made a western training camp a potential option, but O’Malley’s ties to Vero Beach were likely too strong to break; indeed, the team remained there for the duration of the O’Malley family's ownership, which came to an end in 1998. But while leaving Vero Beach was not a realistic option, the O’Malleys knew the Dodgers wielded enormous economic power in the town, and that the moment was now at hand to employ it. Within two days of his meeting with the interracial committee representatives in February 1962, Peter O’Malley had all whites/blacks-only signs painted over in Holman Stadium, including those at entrances, in bathrooms, above water fountains, and most important, in spectator seating, abolishing the "black" section down the right field line past first base. Moczydlowski, "Segregation Outlived Robinson Era," 27; Amore, "Sad Prospects at Vero Beach"; Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams"; Nack, "Dodgertown" At first African American fans were hesitant to move into the "white" sections of the stadium - not surprisingly, given the coercive history of the Jim Crow system - but urged on by black Dodger players, they soon were sitting where they wished. Nack, "Dodgertown" As a sign of respect, Peter O’Malley invited the biracial committee’s Ralph Lundy to sit with Walter O’Malley. Moczydlowski, "Segregation Outlived Robinson Era," 27

In the wake of the integration of Holman Stadium, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner columnist Melvin Durslag observed that Walter O’Malley’s "popularity hasn’t thickened" in Vero Beach. Melvin Durslag, "With Willie It’s Always La Dolce Vita," The Sporting News, April 11, 1962 There was, however, little city officials could do. The dollars-and-cents impact of Dodgertown by the early 1960s was such that they had no choice but to tacitly waive the segregated-seating ordinance, yet another example of the power of economics to affect politics, social relations, and culture. By 1962, under pressure from Major League Baseball, individual teams, and even the state Chamber of Commerce, Florida spring training sites were integrating stadium and residential facilities; the last team to house its black and white players separately, the Orlando-based Minnesota Twins, desegregated its headquarters hotel in 1964. Fred Lieb, "Florida Airs Housing Plans for Negroes," The Sporting News, May 3, 1961, 27; Lieb, "Major League Baseball's Spring Training in Florida," 18-19; Jack E. Davis, "Baseball's Reluctant Challenge: Desegregating Major League Spring Training Sites, 1961-1964," Journal of Sports History, 19 (Summer 1992), 161

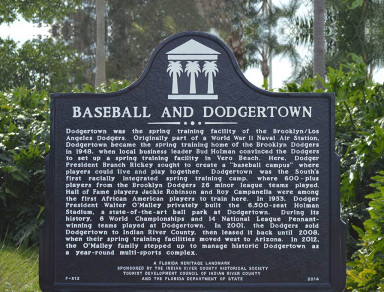

The Florida Heritage Landmark, dedicated at Dodgertown on November 10, 2014, tells the history of Dodgertown and its impact upon baseball and American civil rights. Dodgertown was conceived by team President Branch Rickey and along with co-owners Dearie Mulvey, Walter O’Malley, and John L. Smith, determined the Spring Training base would be integrated for all players. The Dodgers would hold their Spring Training at Dodgertown through the 2008 season.

In taking these steps, baseball franchises, as vehicles of commerce, offered a model for social change that was eventually adopted by the South as a whole. Jim Crow was clearly bad for business. The region’s reintegration into the national economic mainstream, in fact, may have accelerated the process of social change as much as demonstrations, legislation, or oratory. And Dodgertown played an important role in that transformation by offering an example of interracial egalitarianism before other Southern institutions followed suit. The story of Dodgertown, like that of Jackie Robinson, resonates far beyond baseball. Both, in the words of sports columnist Red Smith, "revolutionized the social structure of baseball and, in a lesser degree, the nation." Quoted in Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams"

Today, the fact that blacks and whites can live and work together in an atmosphere of dignity and mutual respect is commonplace. But when we consider that throughout much of its existence Dodgertown may well have been one of the only locations in the South where this was the case, what occurred on its playing fields and in its barracks, dining hall, and movie theatre takes on added meaning. "Jim Crow wasn't buried in Vero Beach by any stretch - its ugly remains haunt us today," writes historian Timothy Gay, "but Dodgertown gave it a swift kick…the people of conscience who worked (there) made our pastime truly national". Gay, "Dodgertown’s Integrated Field of Dreams" As Charles Fountain, author of the spring training history Under the March Sun, reminds us, Dodgertown is "historic for reasons that have nothing to do with baseball." Interview, Charles Fountain, March 13, 2009 www.northeastern.edu/news/stories/2009/03/fountain.html Today, Historic Dodgertown continues that tradition, providing youth from around the world multi-sport training opportunities. Civil rights was the great American moral cause of the twentieth century. Dodgertown’s contributions to that cause make it not just a great sports story, but a great American one.