Spring’s Eternal at Dodgertown

By Brent Shyer

Dodgertown’s Magical Appeal

Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida is literally like a breath of fresh air. Sweet-smelling orange blossoms and rows of trees laden with sun-ripened grapefruit sweep through this modest piece of land that echoes with every player who competed and endeavored to become a major league Dodger.

For 60 years, it was the starting point for each and every Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodger season, a magical place where hope springs eternal and winning and losing pales in comparison to rounding the players into shape.

The smell of the fresh-cut green grass, the streets named for Dodger Hall of Famers and the ultra-modern building which houses the major league clubhouse, weight room, executive offices and training facilities are placeholders of progress for what once was.

The United States built a Naval Air Station at Vero Beach during World War II with temporary barracks to house the servicemen. After the city gained ownership of the base, the Dodgers were approached by local airport manager and businessman Bud Holman to use the site for spring training camp. The Dodgers initially signed a five-year lease and the barracks became home to more than 600 ballplayers, coaches, executives, staff and members of the press.

Holman Approaches Rickey

The Dodgers stumbled upon this small East Coast hamlet in Florida, with nothing more attractive than a U.S. Naval Air base used in World War II, complete with temporary barracks featuring neither heating for the cold nights nor air conditioning for the brutal humidity on scorching spring days in the South.

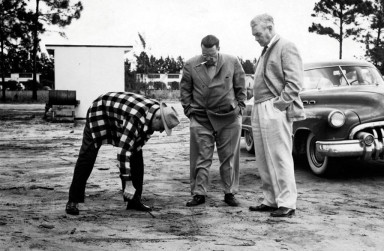

Airport manager Bud Holman (right) welcomes Walter O’Malley to Vero Beach as spring training activities begin at Dodgertown. Holman, an Eastern Air Lines director, initially contacted Branch Rickey and the Dodgers about using the barren U.S. Naval Air Station as a spring training home.

When local businessman and airport manager Bud Holman approached the Dodgers in 1947 about setting up a spring training camp, initially the reaction of Brooklyn brass was somewhat skeptical. But, Holman had done his homework and found that the Dodgers had more farm clubs than any other major league team, thanks to famed executive Branch Rickey’s philosophy of player development.

Rickey had told his family and some close friends that the club was searching for a training site in the United States. Rickey’s daughter mentioned the fact to a neighbor, Dick Cameron, who in turn relayed the information to Holman John L. Klucina, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 22, 1968 .

Holman was convinced that a large facility like the Naval base would be a good fit for the Dodgers and their 26 minor league teams, if they would only visit and give him a chance to prove it. It would take a great selling job in order to snatch the Dodgers for a full-time camp, but that was one of Holman’s fortés. Holman invited Rickey to see the site for himself and took him on a tour of the city. Rickey had a positive reaction to visiting the base, along with his aide Spencer Harris, who would later become the first camp supervisor, but he wasn’t ready to commit just yet.

Bud Holman’s Dilemma

E.J. “Buzzie” Bavasi, then the General Manager of the Dodgers’ minor league Nashua, NH club, was dispatched to Florida to meet with Holman and other civic officials about the plan of converting the Naval base into a spring training camp on November 2, 1947. The 31-year-old Bavasi, who arrived by train, was also to meet with representatives of neighboring Fort Pierce and Stuart the following day to review alternate training sites. The Vero Beach hospitality committee was so overwhelming that Bavasi ended up at a “stag” party on the Holman’s ranch and he spent the night there.

“To make a long story short, I never made it to Fort Pierce or Stuart,” recalled Bavasi. Dodger Edition, Vero Beach Press Journal, March 1, 2002 “Bud Holman met me at the train and he wouldn’t let me go any farther south. The facilities were already there. All we had to do was put in the ball fields. Another thing was having the airport so close. We had our own plane then and we could walk from the airport to the offices. The other places were trying to sell us something. Vero Beach was trying to give us something.” Bill Boeding, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 20, 1988

Holman had a dilemma when the Naval Air Base which had been used for a training field, was given back to the city of Vero after World War II. He was one of a handful of residents who had originally established the airport in 1929. Born in Versailles, KY on September 18, 1900, Holman opened his successful Vero Beach Cadillac Company in 1925. In 1932, Holman had convinced Eastern Air Lines to make Vero’s airport a fueling stop. Holman and Postmaster J.J. Schumann were instrumental in obtaining direct air mail service for the community in 1935, making it the smallest U.S. city to have the service.

E.J. “Buzzie” Bavasi, general manager of the Dodgers’ minor league team in Nashua, NH, traveled by train to Vero Beach to meet with Bud Holman and other civic officials about the possibility of making the former U.S. Naval Air Station the spring training camp for the Dodgers on Nov. 2, 1947. Dodger President Branch Rickey asked Bavasi to review Vero Beach and other Florida cities as spring training sites.

Almost overnight, the airport and Vero Beach became a military community during World War II, after the Navy quickly put up housing on the land where Dodgertown was eventually to stand. Youthful fliers filled not only the skies, but the small Vero Beach land, as well. Dances, parties, church services and hymn sings were held for the military men in the community. Sadly, several were killed in training exercises in defense of the United States. By 1945, the city received the land and training facility back from the U.S. Government under the terms “that any use of the facilities was subject to federal approval and any funds acquired from use or sale of the airbase property must be retained in a special fund and applied exclusively to the maintenance or development of flight facilities.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown The innovative Holman wanted to find a use for the barracks and the base, thus the idea of the Brooklyn Dodgers with all of their farm teams seemed like a feasible solution.

Holman had met with newly-elected Mayor Merrill Barber about the use of the site. They decided to call upon Rickey and ask him to take a tour. The follow-up site inspection by Bavasi was the clincher.

Rickey's Baseball School

Holman duly impressed the Dodgers. He was genuinely interested in having everything fit together perfectly even if it cost him personally, as when he wrote a check to the city for use of apartment buildings nearby Dodgertown, a key to closing the agreement. “We insisted on having those apartments for our staff (married couples) and the press,” said Bavasi. Bill Boeding, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 20, 1988 “We offered them $100 a month for rent of each apartment. But the city balked at the offer. Holman took out his checkbook and asked the value of the buildings. They said $52,000. Holman started to write out a check for that amount. The city fathers refused to sell. Then they rented ‘em to us...and we closed the deal.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown This would be the start of something big. But, progress was as slow in arriving as Vero Beach’s commerce.

When the Dodgers first agreed to make Vero Beach their spring home in 1948, it appeared to officials that the makeshift facilities for fields would be a deterrent to continuing the relationship in the long term. Primitive was too nice a word to be used for the state of the playing fields. “It was just a poor excuse for a baseball field,” said Hall of Fame center fielder Duke Snider.

“We’d carry a fungo bat in case you had to stop and kill a snake on the way,” said former Dodger star pitcher Carl Erskine. Ibid.

Initially, while the camp was functioning as a training and baseball teaching facility under the tutelage of Dodger President Rickey, the poor field conditions meant the Dodgers would play most of their major league exhibition games in front of crowds in Miami Stadium. The minor leaguers played on the various local fields, including next to the airport, trying to dodge snakes, bugs and all other manner of wildlife among the Florida landscape. Rickey started the morning session with a lecture to the hordes of players and coaches.

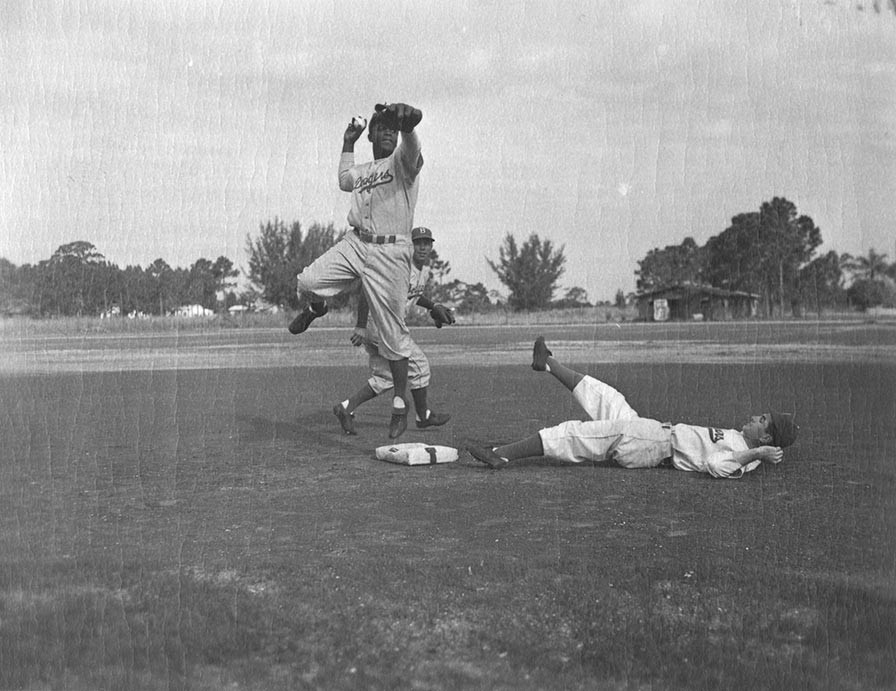

The double play duo of second baseman Jackie Robinson and shortstop Pee Wee Reese get their work done at Dodgertown.

Rickey’s desire to find a spring training site that would permit his new star, Jackie Robinson, who had crossed Major League Baseball’s color line as the first African-American player in 1947, to have some normalcy was extremely important. Most Florida communities planted in the depths of the South discriminated against African-Americans, where segregation was a way of life. According to author Sidney P. Johnston, “Rickey believed that racism was less prevalent in Vero Beach than most other places in the South. African-American baseball players, like all people of their race, encountered discrimination not only in larger cities, such as Jacksonville and Tampa, but in small towns as well. Jackie Robinson aroused protests in Sanford during his first year in the Dodger farm system, while Jacksonville and Deland closed their stadiums to the integrated Dodger farm system.” Sidney P. Johnston, A History of Indian River County “a sense of place”, page 116

Jackie Robinson Emerges

In February 1947, the Dodgers had set up their training camp in Havana, Cuba, a long way from the Borough of Brooklyn, but Rickey strategically wanted to keep his “great experiment” under wraps as long and as quietly as possible. Racial discrimination was less prevalent in Havana, where black players had regularly participated in the Cuban Winter Leagues. Although Robinson would not be housed at the team’s headquarters, the plush Hotel Nacional, he would have relative insulation and a safe haven at the Hotel Boston in old Havana. Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, “The '47 Dodgers on Havana: Baseball at a Crossroads,” Spring Training, 1996 issue

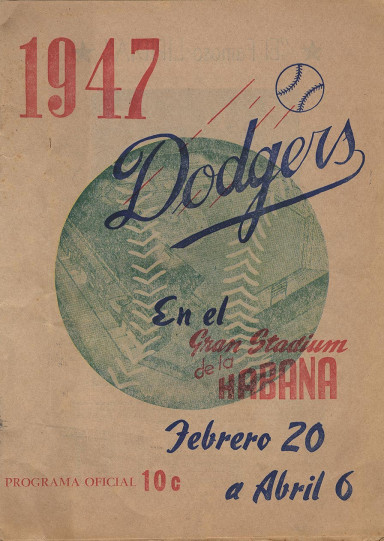

Prior to making Vero Beach their spring training home, the Dodgers were international vagabonds. In 1947, the Dodgers trained in Havana, Cuba, as this program cover for games from February 20 to April 6 shows. Jackie Robinson prepared for his initial season in the majors in relative obscurity. In 1948, even though the Dodgers had established headquarters in Vero Beach for their minor league teams, the major league club trained in Ciudad Trujillo, Dominican Republic and played two exhibition games at Dodgertown and the balance in Miami.

Although, perhaps, that spring training would be remembered for the efforts of baseball to thwart the Mexican League’s attempt to vie for major league talent through high-priced contracts and Dodger Manager Leo Durocher’s one-year suspension for “conduct detrimental to baseball,” nevertheless Rickey had prepared Robinson in the isolation of Cuba for the huge task ahead.

In 1948, the Dodgers would establish camp in Vero Beach particularly for the many minor league clubs, while at the same time maintaining a major league camp again outside of the country. This time, the Dodgers moved locations to Ciudad Trujillo, Dominican Republic, which also provided good weather and less expensive costs, compared to pricey Havana. Attendance in Havana was also lackluster, causing one series between the Dodgers and the St. Louis Browns to be cancelled, plus Cuban fans seemed satisfied to watch their own exciting baseball league. Durocher returned to the field, after his suspension, for the 1948 season.

Scrambling to get the Dodgertown camp prepared for the influx of players, coaches and support personnel by February of 1948, Rickey and Harris had to get the two unused barracks, which had been dormant since the end of World War II, patched, painted and cleaned. Offices had to be established, a mess hall for feeding the masses and recreational facilities developed. Two practice fields and a third with stands were made ready for play. When Bavasi had visited in November and recommended to Rickey to proceed with his plan, weeds were nearly overtaking the barracks. And that was just on the inside.

Rickey promised to give Vero Beach residents a taste of the major league Dodgers when he scheduled two exhibition games on March 31 and April 1, 1948 against the top farm team, the Montreal Royals.

“The Dodgers have an excellent rookie camp in Vero Beach,” wrote Jimmy Powers in the New York Daily News. “The kitchen and equipment room are first class. Vero Beach is much farther north than Miami, as a result too decent and too quiet for the hoodlum element to bother with. Its streets are clean. Its citizens are highly respectable. It has great civic spirit.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

When not eating and sleeping baseball, the minor league players were kept occupied on base with shuffleboard, ping pong tables, a juke box, pool tables, pinball machines and movies three times a week. To further keep the players busy, Rickey wanted a swimming pool to be built and asked Holman and city fathers to start a fund for one to be built by 1949. The innovative Holman guaranteed the construction himself, to be reimbursed using funds from future Dodger exhibition games and thus the pool was built. Wooden street markers around Dodgertown read “Rickey Boulevard, Durocher Trail, Flatbush Avenue and Ebbets Field.”

Dodgertown and Vero Beach, FL are synonymous now. But, in the early years, the Dodgers struggled to draw fans to the complex to watch games. In fact, the majority of Dodger spring training exhibition games were played in Miami.

Vero's First Exhibition

The Dodgers arrived in Vero and were welcomed by Mayor Barber and Chamber of Commerce President William C. Wodtke. Radio station WIRA carried the festivities live. For the two exhibition games, Durocher and his wife, actress Laraine Day, had been assigned one of the barrack’s finest “suites,” but Day found it more than wanting and moved them to the beachfront hotel, the Windswept, five miles away from Dodgertown.

Complementing the lack of heating and air conditioning in the two wooden barracks, each standing two stories high on stilts, were the paper-thin walls. Neither bats nor cleats were permitted inside — bats for obvious reasons and cleats because they would ruin the floors. For most of the players, they would sleep six in a room. “It was a lot like the army,” said Danny Ozark, a former minor league player and later a Dodger coach. Ibid.

With all the pomp and circumstance for their first exhibition game, the Dodgers defeated Montreal, 5-4, as Jackie Robinson homered in the first inning. Florida Governor Millard Caldwell threw the ceremonial first pitch at so-called “Ebbets Field No. 2.” A sign reading “You Are Now Entering Dodgertown” welcomed a strong showing of some 6,000 fans, paying $1.25 in the grandstands and bolstered the idea of more games being played on base in the future. Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler, who had suspended Manager Durocher one year earlier, shook hands with “The Lip” and wished him good luck.

So intrigued by the new facilities was Life magazine that it made Dodgertown the April 5, 1948 cover story and devoted four more pages inside.

A contingent of the Brooklyn National Guard who had traveled to Florida to watch the Dodgers were introduced and went home with a “load of oranges presented to them by the Vero Beach Jaycees.” Special Dodger Section, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 27, 1958

Isolated from the downtown Vero Beach area, Dodgertown enabled the players to be self-contained in the airport area and at the living quarters on base. The Dodgers built up the base so that a player would have all of his basic needs cared for, including their own postal station, canteen, barber shop, Western Union office and lounge.

For the 1948-50 seasons, the Dodgers made the best of the camp as more than 600 players each year ran, ate, slept and played games at Dodgertown. Rickey pushed the players up the ladder with the abundant minor league teams. The cream would rise to the top and every player was graded by coaches and scouts in a host of activities held throughout the day. Versatile Herman Levy, the camp mailman and night watchman, who early each morning would run the American flag up the pole and audibly state the Pledge of Allegiance, blew a shrill whistle that virtually got players jumping from their beds by 6 a.m.

Classes were held to teach the nuances of the game — baserunning, pitching, hitting, fielding, positioning and training techniques. A pitching area known as “The Strings” was established enabling up to six pitchers to warm up and get their practice work done simultaneously. The strings were held on poles in front of the catcher to simulate a strike zone. As the thrown ball passed through the open space of the strings, the pitcher, catcher and coaches could instantly gauge the result, ball or strike. Pitching machines never tired of throwing strikes to batters in fenced off areas. Several sliding pits with sawdust and a base were created. Regular size and half fields were used for practice purposes. A giant brick wall was erected for fielders and pitchers to utilize.

Branch Rickey's Philosophy

Every inch of space at Dodgertown was carved out to maximize the training, education and practice regimen. It was a baseball factory and Rickey, who was the father of the sport’s modern-day farm system, pushed all the buttons.

“Mr. Rickey functioned with clockwork precision,” said longtime Dodger scouting director Al Campanis. “He used the rotation system — a player would rotate from one learning session to another. At night, the faculty would compare impressions with Mr. Rickey who made an analysis of every boy in camp.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

Rickey’s teaching philosophy was emphasized in a column by Walter Stewart who quoted the Dodger President’s speech to the minor leaguers, “We must take pains in order to bring about perfection. One of the purposes of this camp — it’s really a school — is to bring you along as rapidly as possible. You must realize, too, that mere physical lack of skills is not always responsible for failure. The man who gets ahead is the one who makes obstacles into mounting steps. It’s either worth the effort or it isn’t. The average major leaguer was in the minors three to four years. We are trying to make your dream come true earlier. We are developing a system that will bring every hidden player potential to the surface. No other organization can offer these advantages. We will do our best, but what is your contribution? It is you who must make the main effort. The future of the Brooklyn baseball team is here.” Ibid.

Walter O’Malley immediately upgraded the Dodgertown dining room after his ascent to President on Oct. 26, 1950. By spring training 1951, O’Malley had Dodger executives, major league players and the press dining on white linen tablecloths with a full service menu. However, when the minor league players descended on Dodgertown, dining service reverted to cafeteria style and O’Malley would wait in line with players from the various levels.

Dodger Vice President and General Counsel Walter O’Malley, who had been a part-owner of the ballclub since his first acquisition of 25 percent stock on November 1, 1944, was one of Rickey’s partners and was involved in the development of the spring training move to Vero Beach. O’Malley became Dodger President on October 26, 1950 after purchasing Rickey’s 25 percent shares of stock. He immediately promoted Bavasi and Fresco Thompson to Vice Presidents. Bavasi would serve as General Manager, while former Dodger player Thompson also served as Director, Minor League Operations. Charlie Dressen was named as new Dodger Manager replacing Burt Shotton, who was known for wearing civilian clothes in the dugout.

O’Malley longed to find a solution to an aging Ebbets Field problem, with its landlocked piece of real estate and parking for only 700 automobiles. He had communicated with such noted architects as Norman Bel Geddes, Lorimer Rich, R. Buckminster Fuller and Capt. Emil Praeger to exchange ideas about stadium design solutions. The spring of 1951 would be O’Malley’s first in charge of the Dodger organization and he immediately went full throttle to implement needed changes and improvements.

In O’Malley’s first spring training, just four months after being named Dodger President, he upgraded the dining service, run by the Harry M. Stevens Company, who brought in their top chef Fred Boratto to work under dining chief Lester Webb. Dodger executives, major league players and the press ate on linen tablecloths and were able to order off a menu including steaks, loin lamb chops, broiled chicken, veal cutlet, roast beef and calves liver. O’Malley also assigned venerable 30-year Brooklyn employee J. Julius “Babe” Hamberger to the salon to greet and take care of the press and visiting dignitaries. Hamberger did virtually everything for the Dodgers, including traveling secretary, ticket seller, ticket taker, turnstile boy, concessions employee, sweeper, scoreboard operator, groundskeeper, announcer and clubhouse man. Joe King, The Sporting News, March 7, 1951 Players and camp personnel consumed some 86 gallons of fresh orange juice each day of spring training that year. Special Dodger Section, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 27, 1958

O’Malley Develops Dodgertown

O’Malley, who played the perfect host, held a “happy hour” every night before dinner with his wife Kay and then, after dinner, would enjoy playing poker. He also improved conditions in the barracks by adding siding for insulation. Many nights were down to freezing in 1951. Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

A headline in The Sporting News in 1951 pronounced, “Bums Go From Rags to Riches at Camp,” as Dodgertown was upgraded under the leadership of O’Malley. Ibid. On March 18, 1951, Vero Beach residents rejoiced over the dedication of the new $800,000 Merrill Barber Bridge, spanning the Indian River.

O’Malley had a whirlwind first season in 1951, one that established his role within the game as a full-time owner and not as a hobbyist like so many of his peers, as he was named to the important Major League Baseball Executive Council. The 1951 season, however, ended as one of the most painful to Dodger fans, as the New York Giants beat Brooklyn in a three-game playoff series to determine the National League Pennant-winner, two games to one. The famous “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” by Bobby Thomson did the Dodgers in and it was once again “Wait ‘Til Next Year.”

O’Malley, though, did not like waiting until next year at any time. Not when he could get something done in the current year. While the search continued for a new home in Brooklyn to remedy Ebbets Field, which opened in 1913, the idea of building a new spring training home stadium very much appealed to O’Malley. Previously, the Dodgers had to split time in Vero Beach and in Miami, about three hours south. O’Malley was going to use Vero Beach not only as a training ground for ballplayers, but for one of his fine architects.

O’Malley’s idea was to use the ballpark as a sort of tryout for Capt. Praeger to design a stadium with unobstructed field views at reasonable costs. Of course, O’Malley had a much grander plan for Brooklyn in mind — a 50,000-seat domed stadium — but the Vero Beach job was just as important to him on a smaller scale. He would learn more about the process of building his own stadium, the pitfalls, the expenses (both known and unforeseen) and the timeline for construction. The type of construction first implemented at Dodgertown would be a precursor to that used by O’Malley years later in Los Angeles. As a fan of the nice, quiet Vero Beach community, O’Malley believed that a long-term relationship with the city would be just right. In fact, it was an area where distractions were kept to an absolute minimum and that suited O’Malley and staff perfectly. If they were fortunate, the players were entertained by walking from the base to the city’s only movie theatre downtown and back. But, he did not want the transient Dodgers to cause any trouble for the community in the two months of training camp.

According to the March 13, 1952 Vero Beach Press Journal, “President O’Malley has consistently stated that he has faith in the future growth of Vero Beach and the surrounding area. He feels that, in the future, Vero Beach and the surrounding area, will be in a position to support a larger exhibition schedule. If a large number of fans turn out and indicate that they want to see big league ball played in Vero Beach, Mr. O’Malley has assured them that they will get it.”

21-year Lease Signed

A vision of the future was dancing in his head and O’Malley shared it to the world in 1952, when he agreed to build a permanent home stadium at Dodgertown. He knew the original agreement was to expire in 1953. The Dodgers would sign a 21-year lease agreement with the City of Vero Beach, whose officials had voted unanimously, to make Dodgertown their spring training headquarters during the week of January 31, 1952. The agreement enabled the Dodgers to “renew for an additional period of 21 years.” Julie Autumn Luster, 2002 Dodgers Spring Training Yearbook, “Holman Celebrates Half a Century” No other major league club had a longer running spring contract. The terms of the lease were $1 a year for 21 years, which O’Malley, a non-practicing attorney, paid in cash upfront to avoid a lot of legal issues in the contract.

It would be the first major statement that had been made by the Dodgers that indeed they were there to stay. The terms “called for the Dodgers to have their team in Vero Beach at least 15 days each spring. A certain number of exhibition games were to be played, the Dodgers were to pay the city $3,000 to complete the debt on the swimming pool and earmark the entire receipts from one exhibition game for the airport fund.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown A Vero vote of confidence and one appreciated by the local city fathers, who immediately realized the financial, public relations and hospitality impact of O’Malley’s commitment.

Dodgertown’s mess hall is the gathering point for all hungry players, staff and executives. But, feeding the masses cafeteria style meant waiting in line and eating in shifts. Walter and Kay O’Malley stood in line holding their aluminum trays shoulder to shoulder with the players.

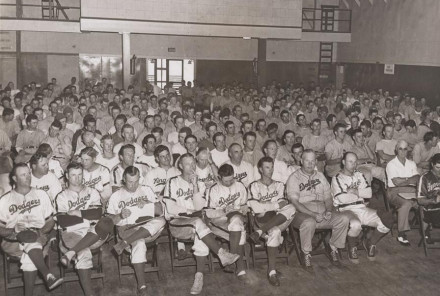

Dodger players attend a baseball skills class in the old Dodgertown auditorium. Branch Rickey’s initial vision for a training camp included educating the players about all aspects of the game.

O’Malley never scaled the pinnacle of superiority in his actions, as could be seen by every one of the ballplayers at Dodgertown. When the many minor league teams descended on Dodgertown and table service reverted to cafeteria style, the Dodger chief and his wife, Kay, stood in line with their aluminum trays for food in the mess hall dining room just like everyone else. Class D ballplayers waited in line shoulder to shoulder with Class B, major leaguers and the Dodger President himself. That was one of the most unique facets of Dodgertown and part of the reason for its success. This was no nameless, faceless organization, but one that gathered the “troops” together and made everyone feel a part of the larger family. By meeting and talking with the masses of individuals each day, the Dodgers became stronger and more unified.

“One of the main advantages of a central training camp is fraternization,” wrote Thompson. “The players with all clubs become acquainted with one another; firm friendships develop. During the season if a player should be transferred from one club to another, or when the Dodgers cut down to their active limit of twenty-five, he goes to a club where he is not a stranger to the players or the manager.” Fresco Thompson, “Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle,” David McKay Company, Inc. 1964 copyright, page 131

The plan O’Malley devised for Dodgertown was to systematically upgrade the entire complex, maintaining the basic features that made it work from Rickey’s regime and enhancing it to become more player and fan friendly. He believed the more players felt at home at Dodgertown, by catering to their every need, the less likely they would wander off base for outside entertainment. O’Malley wanted to have the most state-of-the-art spring training complex, with the best training techniques, meals, medical facilities, stadium, landscaping and recreational facilities. A player might never leave base during his stay, except to attend a weekly religious service of his choice. And the Dodgers even provided bus transportation for that. Although the goal never changed, which was to address the well-being and conditioning of the players while preparing them for the season, O’Malley saw opportunity in Dodgertown, that the real beauty of it was that it could be a self-contained retreat, not just for a couple of months in the spring but with year-round possibilities.

O’Malley Proposes Stadium

In 1952-53, O’Malley began to transform Dodgertown into his vision as the finest spring training site in baseball. His first step was to build a stadium with fan-friendly amenities for the loyal Vero Beach following. On March 7, 1952, O’Malley announced at a press conference in Miami that there was “a strong possibility that the Brooklyn Dodgers will build the proposed new 5,000-seat stadium in Vero Beach.” Bob Curzon, The Vero Beach Press-Journal, Sports, March 13, 1952 O’Malley noted that respected Capt. Praeger, who was consulting engineer on the United Nations building in 1953 and the White House renovation in 1949, had spent several days in Vero Beach and submitted construction cost estimates.

O’Malley wrote a letter to Holman on May 15, 1952 stating in part, “As you know, it is my intention to demonstrate, in a practical way, that the Dodgers are permanently interested in Vero Beach and in that direction we propose to build a beautiful concrete stadium seating 4200. Such a stadium will have great value to the City of Vero Beach as well as to the Dodgers.

Bud Holman (left) bends down and checks the soil as Walter O’Malley and noted designer Capt. Emil Praeger review a possible site for a new stadium at Dodgertown.

“You will note from the plans that the new stadium lends itself to 4200 desirable seats in the event that football games are to be played there. Temporary bleachers can also be erected on the open side of the field which I am told, can accommodate 2500 people. Should some regional or especially important football games develop, the Dodgers would be willing to have the new stadium used for that purpose on a rental basis of 25 cents per paid admission plus the actual cost of converting the field from baseball to football conditions and the return of the field to baseball conditions...I have tried to make the rental as low per seat as possible but still commensurate with the substantial investment that we will have.

“You will understand that a good many people will question our wisdom in spending this amount of money in a spring training stadium, particularly when it is normally one of the inducements that the different cities offer the various ball clubs to train there. I justify the investment, not on the immediate future but on a long range forecast. I believe that Vero Beach will develop a greater interest in baseball than has been shown so far. You are familiar with the attendance figures for the two major league exhibition games we played this year. That attendance, obviously, is not an attraction to other clubs to book games with us at Vero Beach but there is a possibility with a new stadium and greater public support we can justify the playing of many more of our spring exhibition games at our winter home in Vero Beach.”

Also that month, O’Malley wrote to executive Wid C. Matthews of the Chicago Cubs regarding the possibility of sharing a spring training site, today a common practice, in Vero Beach. The Cubs had just moved camp to Mesa, AZ, after seven years at Catalina Island, CA, in 1952. “We believe that two organizations could train in the same town if we had separate fields and eating and sleeping quarters,” O’Malley wrote on May 5, 1952. “We would not be too much concerned about the problem of fraternizing. I have in mind we would give you a 21 year sub-lease or we might arrange to surrender those premises and have the new lease made out directly to your organization. You know from the general location that there is ample room for you to expand, should you wish.” Letter by O’Malley to Wid C. Matthews, May 5, 1952

Emil Praeger Design

The Dodger Board of Directors authorized the construction of a stadium in Vero Beach on June 10, 1952, noting “FURTHER RESOLVED that this Board of Directors thank the City Council of Vero Beach for their cooperation in making the building of the new stadium in Vero Beach possible.”

On July 16, O’Malley named H.J. Osborne as the contractor to construct the stadium, which was designed by Capt. Praeger with considerable input from O’Malley, whose expertise included an engineering background from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a two-time class president. Osborne had 90 days to complete the “grading, concrete, fill work, ramps and fence.” Vero Beach Press-Journal, July 17, 1952 Interestingly, a newspaper account reported that noted architect Norman Bel Geddes, who had designed Futurama at the New York World’s Fair, was to be involved on the stadium project, instead of Praeger was incorrect. In O’Malley’s handwriting on an official Dodger press release draft, he wrote the words, “Geddes has nothing to do with this job.” Apparently, since both Bel Geddes and Capt. Praeger had been to Vero to meet with O’Malley it had caused the later confusion. Bob Curzon, Vero Beach Press-Journal, March 13, 1952

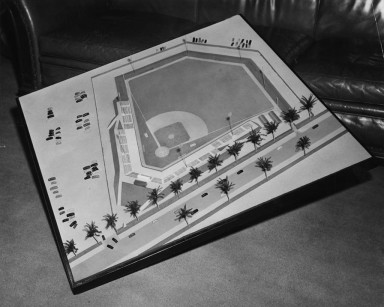

A model of Holman Stadium, which was built in a unique and cost-efficient manner, as the dirt was pushed up to form a bowl and an embankment, a signature part of the ballpark’s setting.

In fact, O’Malley wrote a letter to Bel Geddes on December 11, 1952 stating, “Have a good trip to Jamaica and enjoy your three months there...Capt. Praeger and I are trying to stimulate some interest in a new stadium (in Brooklyn) and if we get any place, there might be an opportunity for you to volunteer your unique talents. You will be interested in knowing that we completed our little stadium at Vero Beach in 55 days, 5000 seats at a cost of $30,000. We are quite pleased with the result.” O’Malley letter to Norman Bel Geddes, December 11, 1952

O’Malley desired a stadium which had perfect sightlines — no poles to obstruct the customer’s view of the field. He also wanted an intimate ballpark, especially capturing the feeling of bringing the players and fans close together during spring training. After all, these were only exhibition games that were to be played in Vero Beach.

Construction carried on throughout the course of the fall. Contracts were awarded for various parts of the stadium construction, including seats, press box, lights and refreshment stands, lowering costs and expediting the process. Local contractor C.R. Cruze handled the contract to build dressing rooms, public toilets and press box. Jesse Swords was low bidder on the land preparation work, while Osborne handled the concrete work. Originally, O’Malley decided on a 4,200-seat stadium, but later announced the total capacity had been expanded to 5,000. Some 2,000 portable stadium seats from the Polo Grounds were purchased for one dollar per metal chair by O’Malley from Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants. O’Malley letter to Horace Stoneham, November 18, 1952

In a letter to David Bissett, Superintendent, Plant Introduction Garden of the U.S. Department of Agriculture on October 16, 1952, O’Malley wrote, “We have just completed the building of an unusual type stadium. The stadium was built by excavating 20,000 cubic yards of sand, marl and muck. The excavation from which this fill was obtained has now been made into a two acre fish lake and is being stocked by the United States Wild Life Service. The fill formed in mounds which were compacted and rolled, over which four inch reinforced concrete was poured to make the stands. We are anxious to achieve a maximum of attractiveness by way of unusual plantings as the design of the stadium depends on the plantings for eye appeal.” O’Malley letter to David A. Bissett, Superintendent, Plant Introduction Garden of the United States Department of Agriculture, October 16, 1952

When Vice President, Minor League Operations Thompson first saw the new stadium he said, “It is much more than I expected. It is one of the most beautiful little stadiums I have ever seen.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

Walter O’Malley and Bud Holman shake hands at the dedication ceremonies for Holman Stadium on March 11, 1953. Though he became a rabid Dodger fan, initially Holman knew little about baseball. As an astute businessman, he saw and acted on the opportunity to bring the Dodgers to Vero Beach for spring training. The plaque presented by the Dodgers reads, “The Brooklyn Dodgers Dedicate Holman Stadium to Honor Bud L. Holman of the Friendly City of Vero Beach, Walter F. O’Malley, President, Emil H. Praeger, C.E., Designer, 1953.”

Holman Stadium Dedication

Early in January 1953, O’Malley told the press that the stadium would be named for a Vero Beach citizen. Then, on January 15, O’Malley said in his announcement, “From the time Branch Rickey came to Vero Beach, Bud Holman has continually sparked the development of the (Dodgertown) project.” The Vero Beach Press Journal of January 15 concluded, “The entire Dodger organization was deeply appreciative of the fine co-operation received from the citizens and officials of Vero Beach and felt that it was highly appropriate that the stadium be named for one of its citizens — a man who had devoted much of his time and effort towards making Dodgertown possible.

“Holman Stadium at Dodgertown stands as a tribute to the man who brought to Vero Beach one of the biggest attractions and businesses in the United States.” Bill Boeding, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 27, 1993

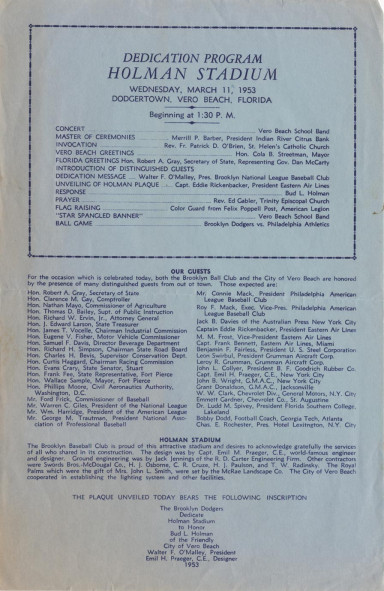

On March 11, 1953, the dedication day program insert for the first game played at Holman Stadium, Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida by two major league teams when the Brooklyn Dodgers defeat the Philadelphia A’s. Among those attending the dedication are Connie Mack, Hall of Fame manager and part-owner of the A’s; Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick; National League President Warren Giles; and American League President Will Harridge.

The construction process was unique and fast, as dirt dug out from the field was used to create an embankment for the outfield. There would be no outfield fence, just a grass slope. In a June 18, 1954 letter to St. Louis Cardinals’ Vice President William Walsingham, O’Malley explained, “The Vero Beach stadium was let on competitive bidding. The excavation, fill, mounds, concrete and reserve seats cost $50,000 even for 5000 seats. The house is scaled very high in favor of box seats of which there are 40% or 2000. This percentage can be varied depending on local conditions.

“The lights came from our abandoned Cambridge, Maryland park so there is no true cost figure on that. The ticket office, 4 public toilet rooms and clubhouse with plumbing cost $12,000, the press box $1000.

“This stadium is by far the cheapest I have ever known to have been built and we did it more or less as an experiment to show minor league people that it would be possible for a modest outlay to have a new and attractive stadium replace the horrible minor league monstrosities in which most teams now play.”

The dedication of the new ballpark, O’Malley’s pride and joy, was on Wednesday, March 11, 1953. In preparation for the big day, the Vero Beach Press Journal reported that “we spied an extra workman among the ground crew working on the infield the other day. The fellow was busy raking the soil part of the new infield. He looked familiar to us and he rightly should...He was Walter F. O’Malley, president of the Dodgers.” Bob Curzon, The Dodger Bullpen, Vero Beach Press-Journal, March 12, 1953

The Dodgers played the Philadelphia Athletics that day and an overflow crowd of 5,532 attended the first game at Holman Stadium. The 1:30 p.m. dedication ceremonies began a little late but included a concert by the Vero Beach School Band; Merrill P. Barber, the President of the Indian River County Citrus Bank as the emcee for the official festivities; and an invocation by Rev. Fr. Patrick D. O’Brien of St. Helen’s Catholic Church in Vero. Distinguished guests included Florida Secretary of State Robert A. Gray, representing long-time Governor Daniel McCarty, who had suffered a disabling heart attack only two weeks prior, Florida, a Division of Historical Resources web site, Florida Governors’ Portraits, Daniel Thomas McCarty politicians from Vero, Ft. Pierce and Stuart, the Commissioner of Baseball Ford C. Frick, the President of the National League Warren Giles and the President of the American League William Harridge. The festivities were carried live on radio.

Dodgers Win Opener

O’Malley made several key introductions and gave the dedication message and followed that with the unveiling of a plaque for the stadium which read, “The Brooklyn Dodgers Dedicate Holman Stadium to Honor Bud L. Holman of the Friendly City of Vero Beach, Walter F. O’Malley, President, Emil H. Praeger, C.E., Designer, 1953.”

M.M. “Jack” Frost, Vice President of Eastern Air Lines, stood in for Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, President of Eastern Air Lines, and unveiled the plaque with O’Malley. Holman briefly responded to the honor and that was followed by a prayer from Rev. Ed Gabler of the Trinity Episcopal Church, flag raising ceremonies by the color guard from Felix Poppell Post, American Legion and the national anthem by the band.

In the first game at Holman Stadium, the Dodgers defeated the Athletics, 4-2. The Athletics, with their part-owner and President Connie Mack in attendance, scored the first run in the top of the first inning, but Brooklyn bounced back with three runs in the bottom of the first. Right-handed pitcher Carl Erskine allowed just one run and four hits as the starter for the Dodgers, while center fielder Duke Snider drove in two runs in a three-run first inning for Brooklyn.

Walter O’Malley and Connie Mack, Philadelphia Athletics part-owner and longtime former Manager Connie Mack exchange pleasantries at the Holman Stadium dedication on March 11, 1953.

Erskine recollects, “I pitched the opening game and got the win. I have some home movies from that game. There’s a shot of Mr. (Bud) Holman and Mr. (Walter) O’Malley with the plaque dedicating the stadium. Someone took shots of me pitching from the bench, which was on the first base side back then. There’s even a picture of me getting a base hit. It was a big day.” Dodger Spring Training Yearbook, 2002, Vero Beach Dodgers

Aesthetics of a stadium were always high on O’Malley’s list, whether in Brooklyn, Vero Beach or Los Angeles. As a horticulturist in his personal life, O’Malley found solace in getting away from his rigorous work schedule to grow orchids in his greenhouse in Amityville, NY. The use of color and landscaping in a stadium were important elements to O’Malley. A heart-shaped, man-made lake was built behind Holman Stadium, as a tribute to his beloved Kay. Later, her favorite saying came from the musical Damn Yankees, “You’ve gotta have heart.” O’Malley wanted something to enhance the setting of Holman Stadium, to remain as an on-going monument to the Vero Beach community for years to come. The answer became one of Holman Stadium’s most unique features. O’Malley dotted the outfield with Royal Palms, a landmark, of sorts, for the ballpark and an addition that grew in popularity over time. To honor her husband, Mary Louise Smith, the widow of O’Malley’s business partner John L. Smith, wrote a check to donate the cost of the 50 Royal Palm trees gracing Holman Stadium. Frank McGrath, Fall River, Mass., Herald News Sports, March 19, 1954

From that first game at Holman Stadium, the entire Dodgertown site received rave reviews. The experiment to build a reasonably inexpensive stadium with modern amenities, through Capt. Praeger’s design, had worked to perfection. But, for the next four years, O’Malley’s focus shifted to the important task of finding a suitable site on which to build his masterpiece, a 50,000-seat domed stadium in Brooklyn.

The business of baseball interfered with O’Malley’s grand opening of Holman Stadium. According to the Vero Beach Press-Journal on March 26, 1953, “It was at the dedication game that Lou Perini, owner of the Boston Braves found Ford Frick, Warren Giles, Will Harridge and Walter F. O’Malley, all members of baseball’s executive committee. It now can be told. The five men missed the Athletics-Dodgers game. They left the stadium after the dedication ceremonies and held a meeting. Their discussion on Wednesday afternoon, March 11, laid the groundwork for the moving of the Braves from Boston to Milwaukee.” Bob Curzon, Vero Beach Press-Journal, March 26, 1953

Vero Beach History

The eventual transfer of the Braves would be a key to opening the door for relocation in the National League, as no movement had occurred by franchises in 50 years. But with the Braves’ shift to Milwaukee for the 1953 season, the Dodgers in Brooklyn and the Giants in New York, both playing in stadiums built or renovated in the 1910s, had to at least take note of possible opportunities in the future from alternate sites. As Milwaukee’s attendance was nearly twice that of the Dodgers, O’Malley felt added pressure to resolve the new stadium issue for fear of not being able to compete with the Braves.

The city of Vero Beach could not have been prouder of new Holman Stadium. For Holman, the honor was one of civic pride in the small-town community, though his son Harry “Bump” Holman stated in an interview about his father, “He really didn’t know anything about baseball.” James Kirley, Vero Beach Press-Journal, February 20, 1988 However, Bud Holman knew spring training baseball was good for the community and he later became a rabid fan of the Dodgers.

The name of Vero Beach is somewhat of a puzzlement. Though theories abound, one of the most popular ones is when “Henry T. Gifford asked the United States Post Office for permission to establish a post office in his own home (on September 28, 1891). Ironically, on the application it appears the U.S. Postmaster thought ‘Vero’ was an error, and he wrote over the first letter and put a ‘Z’ to make it ‘Zero.’ Mr. Gifford corrected the postmaster by drawing the letter ‘V’ with very thick lines.” Pamela J. Cooper, Indian River County Main Library, Florida History & Genealogy Dept., Dec. 3, 1996, rev. April 2001 Some believe that Gifford’s wife was actually named Vero. Whatever its actual origin, Vero Beach grew in popularity and prominence largely due to the vast publicity it received after the Dodgers arrived there. The writers from New York put Vero Beach datelines on their stories, explored surrounding attractions such as the McKee Jungle Gardens and it was not too long before the lure of warm weather and the Dodgers brought many snow birds south to see it for themselves. Some permanently fled the snow and city life of New York for the slow-paced Eastern seaboard town.

While nothing is ever easy when dealing with cities and municipalities as O’Malley would repeatedly find out whether it was in New York, Vero Beach or Los Angeles, he did what he needed to do to keep advancing forward. In Vero Beach, the city had agreed to turn over gate receipts of two spring exhibition games to the Dodgers in order to have the ballclub install lights on “No. 3 Field,” as it was called at Dodgertown. But, since the 1952 arrangement would precede the new construction, O’Malley and the Dodgers wanted to wait and transfer the installation of lights to Holman Stadium, which would also permit use of the park for other city sports activities. Holman himself wrote O’Malley in Brooklyn and tried to assist in smoothing over the Vero Beach City Council members who were opposed. Eventually, a deadline for installation of lights was extended per O’Malley’s request from June 15 to July 30 to work everything out satisfactorily.

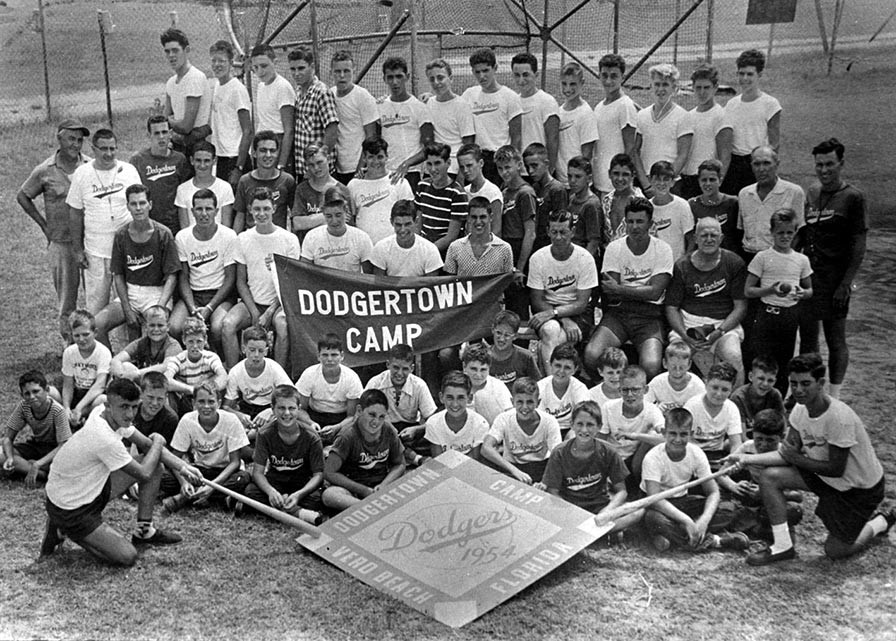

Citing year-round potential for the complex, Walter O’Malley launches the Dodgertown Camp for Boys. Campers at the initial 1954 session paid $500 for two months housing, all meals and sports instruction under the directorship of track star Les MacMitchell. Peter O’Malley was a 16-year-old camp instructor, while his sister Terry served as a secretary for the camp’s administration.

Dodgertown Camp for Boys

The Dodgers won back-to-back National League Pennants in 1952 and 1953, but in both seasons finished on a losing note in the World Series against the rival New York Yankees. In 1954, there was a new manager when the club arrived in Dodgertown, as O’Malley had hired solid baseball man but relatively unknown Walter Alston. The quiet but firm Alston replaced Charlie Dressen, who had failed in his demand for a three-year contract, which was against existing club policy of one-year deals. Alston had been a fixture in Vero Beach for years as a successful minor league manager. His 1953 Montreal Royals club defeated the New York Yankees’ Kansas City Triple-A team to win the “Little World Series.” Alston would go on to sign 23 consecutive one-year contracts under O’Malley and be enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The Dodgers played four spring exhibition games and 96 total organization games at Dodgertown in 1954.

“Each year my wife Lela and I drove to Vero Beach from our home in Darrtown, Ohio. But 1954 was special. I was the manager now, not a minor league skipper,” said Alston. “I couldn’t wait until it was time to start spring training. I would be anxious to see which kids were ready to move up. It was exciting to speculate about who would be the next discovery.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

It was also in 1954 that an energetic and talented broadcaster named Vin Scully took the lead role, a position he held through 2016.

“There’s not a place in the world that has as many memories for me as Dodgertown,” said Hall of Fame broadcaster Scully, who was a regular at Dodgertown since 1950 and has a street named for him there. “My first year, they didn’t know what to do with me. So, I slept on a cot in a little room off the main lobby.” Dodgertown: A Trip Through History, Josh Rawitch, MLB.com, February 17, 2002

To help defray some of the year-round expenses of maintaining Dodgertown and to reach out to youngsters, O’Malley and his staff developed a Dodgertown Camp for Boys ages 12-16 initiated in July and August of 1954. O’Malley did his homework regarding sports camps, writing to Ed Steitz at Springfield College for background materials on running a camp. Springfield was recommended to O’Malley as running a model camp program that was the best in its field. When the Dodgertown Camp for Boys began it was to be an all-sports camp, promising an opportunity to receive instruction in baseball and a variety of recreational activities, including swimming, tennis, fishing, basketball and shuffleboard, all while living on base.

The camp started under the directorship of Les MacMitchell, a former New York University track star, with assistance from Bill Ceccotti and Buck Lai and some 50 counselors. Terry O’Malley, Walter and Kay’s daughter who had just graduated from New York’s College of New Rochelle, joined the camp administration as secretary. Nearly 200 boys from throughout the country were sent to the prestigious camp from July 1 to August 25, 1954, paying $500 for all expenses, to train where the Dodgers did. One of the camp counselors that first year was O’Malley’s 16-year-old son Peter, who would, years later, run the entire Dodgertown complex (Jan. 1962-Jan. 1965) and succeed his father as Dodger President on March 17, 1970. Peter had made headlines in the Vero Beach Press Journal at age 15, when he lost an identification bracelet he wore in the Dodgertown swimming pool. An unidentified woman found it and returned it to the Dodger office. While Walter and Kay O’Malley would have been pleased to offer their thanks and a reward, none was asked for and they were impressed with the honest citizen. Vero Beach Press-Journal, March 13, 1952

St. Patrick's Day Tradition

The camp grew in popularity and started accepting boys ages 10 to 16 in subsequent years. O’Malley always found time to make an annual visit to the camp, even taking an Atlantic Ocean dip with some of the boys. Campers found the following message in the recreation halls, “George Washington didn’t sleep here, but Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Carl Erskine and other Dodgers did.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

In spring training, to rally the troops in what otherwise can be a long couple of months, O’Malley helped to break up the monotony by starting the tradition of St. Patrick’s Day parties at Dodgertown on March 17, 1952. He actually staged one in his first year in Miami Beach, but these grand affairs would continue to grow and become somewhat legendary. Fond of saying, “Half the lies they tell about the Irish aren’t true!” O’Malley’s lineage can be traced directly to County Mayo, Ireland on his great-grandfather’s side. His first party was held off-base at the popular visitors’ destination of McKee Jungle Gardens, about 15 minutes from camp. The party actually was held around an enormous 35-foot one-piece mahogany table in the “Hall of Giants” and featured music and skits in a well-decorated grand hall. Dodger trainer Bill Buhler was asked to supervise the decorations for these special parties which were later held in the old Dodgertown auditorium and finally in the on-base dining room. They were the highlight of each spring and allowed everyone to relax and share some laughs, whether they were invited players, like Maury Wills playing the banjo, or VIP guests, executives, staff and media. It was O’Malley’s big party and he certainly knew how to throw one, complete with green derbies, skits, Irish music, green beer, green ice, corned beef and cabbage and all the trimmings.

All of Vero Beach, like Brooklyn, celebrated with enthusiasm when the Dodgers won their first World Championship in 1955. Preparation for the season at Dodgertown was in evidence as the club jumped out of the gate to win their first 10 and 22 of 24 games. Bums no more, the Dodgers finally tossed their “Wait ‘til next year” mentality away and stood atop the baseball world under second-year Manager Alston. O’Malley spent much of his time running in circles with New York politicians trying to find a solution to the problem of Ebbets Field.

In the meantime, two developments paved the eventual way for O’Malley. First, he acquired the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels, territorial rights and Wrigley Field in Los Angeles from Philip K. Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, in exchange for the Dodgers’ Fort Worth Cats team of the Texas League on February 21, 1957. Second, Los Angeles emerged as a suitor, as city and county officials there wanted to upgrade from the PCL to Major League Baseball. On September 23, 1954, a letter of interest was sent to all Major League owners by City Clerk Walter C. Peterson. L.A. City Councilwoman Rosalind Wiener Wyman had written O’Malley a letter of interest as early as September 1, 1955 asking for a meeting in New York to which he declined. On a brief stopover from New York enroute to Hawaii and eventually to Japan to play 19 games on a Dodger goodwill tour, O’Malley met with Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and other officials on October 12, 1956 at L.A.’s Statler Hotel.

Another important meeting took place with several representatives from Los Angeles, including its Mayor Norris Poulson and Hahn, at Dodgertown on March 6, 1957. Also in attendance were John Gibson, President of the City Council; Samuel Leask, City Administration Officer; John Leach, Los Angeles County Chief Administrative Officer; and Milton Arthur, Chairman of the County Recreation Commission. It was an opportunity for Los Angeles to put its best foot forward and explain its genuine hope of pursuing the Dodgers and bring Major League Baseball to the West Coast, while gauging O’Malley’s interest. During their visit and throughout that spring, Emmett Kelly, the world-famous clown, entertained everyone and his antics were well-received by the fans.

O’Malley, Praeger Team Up

After months of discussions with officials both in Brooklyn and Los Angeles throughout the summer of 1957, O’Malley finally chose his course of action. On Oct. 7, 1957, the Los Angeles City Council agreed to enter into a contract with the Dodgers. The next day, the Dodgers announced they were indeed moving to Los Angeles for the 1958 season, making Major League Baseball coast to coast.

In a period of change, especially for the players and front office staff, Vero Beach was the one constant, a place called “home” for two months of spring training that had a familiar and special feel to it. Dodgertown employees who remained through the years became friends of the ballplayers, staff and front office, unifying each camp. It was three-time National League MVP Roy Campanella captivating players and staff, who sat in a semi-circle, with his stories, anecdotes and instruction in an area outside the camp kitchen and clubhouse which permanently became known as “Campy’s Bullpen.” It was poker games by the sportswriters and team executives, including O’Malley, late into the night. It was wives gathering poolside to chat, tan and relax in the hot Florida sun. It was photographers Herbie Scharfman and Barney Stein doing their professional magic and recording for history the activities of each camp. It was Manager Alston slamming his 1955 World Series ring against Larry Sherry’s door and cracking the diamond-studded stones in anger over the noise made by pitchers Sherry and Sandy Koufax returning to base after curfew. It was Nurse Anatasia Plucker dispensing her “salt solution” in paper cups to players suffering from heat exhaustion. PPascal James Imperato, M.D., “Himself, Mrs. Plucker, and the rites of spring, New York State Journal of Medicine, February 1989, Page 87 It was Charlie Ehrmann running the Dodgertown canteen, while his wife “Archie” worked in the business office. It was a local welcoming committee and thousands of fans at the Vero airport when the Dodger plane arrived to break the seal on another spring season.

While O’Malley had his hands full with the business matters in Los Angeles, especially his efforts to initially find a place to play and then finally build his dream stadium there, Dodgertown continued to thrive. In 1957, Piper Aircraft Company arrived in Vero Beach set up its “research and development center on the grounds of the former Naval air station.” Sidney P. Johnston, “A History of Indian River County”, Page 118 The additional industry and population would also help the area’s beginning as a resort town.

On March 31, 1961, famed evangelist Dr. Billy Graham held a Good Friday service at Holman Stadium during his Florida Crusades, joined by a Crusade choir of locals numbering nearly 400. Vero Beach Press-Journal, March 30, 1961

O’Malley completed Dodger Stadium, his 56,000-seat showplace in Los Angeles, in 1962. It was the first privately-financed stadium since Yankee Stadium opened in 1923. The topography of the Chavez Ravine area was so hilly, that construction teams had to move some eight million cubic yards of earth. But, both Holman Stadium and Dodger Stadium were designed similarly by Capt. Praeger and O’Malley, as they literally took the dirt and pushed the ground up to form the sides of the bowl. Both stadiums have unparalleled sightlines and fans are close to the action. And, they both have colorful landscaping that adds to the ballpark’s natural beauty.

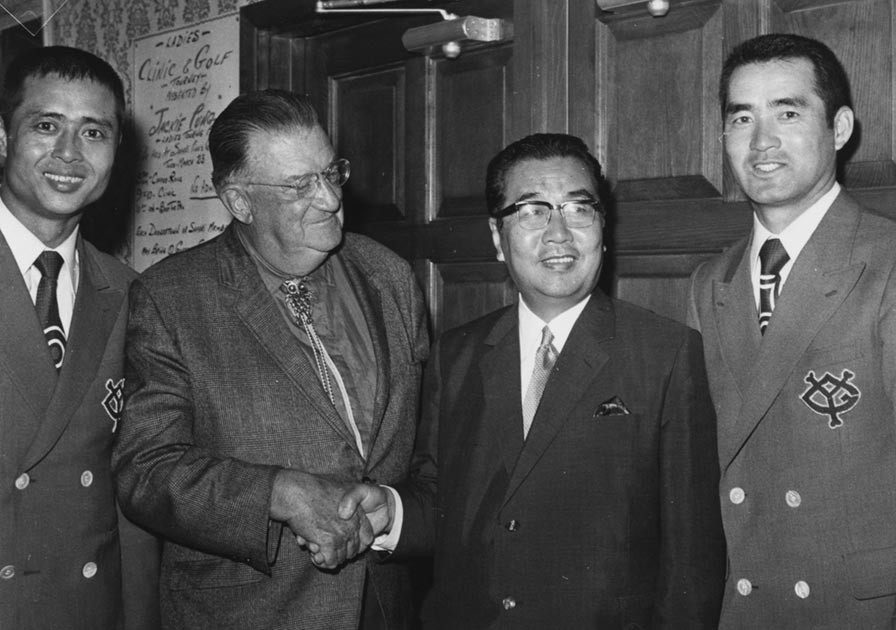

Yomiuri Giants slugger Sadaharu Oh, Walter O’Malley, Giants President Toru Shoriki and Giants four-time Japan Series MVP Shigeo Nagashima enjoy another cultural exchange at Dodgertown in 1971. The Giants won the 1971 Japan Series.

Foreign Visitors Welcomed

International relations were always important to O’Malley as a way for countries to reach unity through baseball. He arranged for the Dodgers to play a 19-game goodwill tour in Japan in October-November 1956. In an unusually wet 1959 spring in Vero Beach when it rained six straight days, O’Malley arranged for the Dodgers to fly to Havana, Cuba to get their work done and play the Cincinnati Reds with Fidel Castro present. Holman’s son, Capt. H.R. “Bump,” one of the team’s pilots, flew the Dodgers to Havana in the team-owned Convair. The Dodgers would use their training camp, Dodgertown, to promote cultural exchanges and baseball education in later years. Peter O’Malley continued the tradition and encouraged numerous international visits from throughout the world. Vero Beach was the site of many of these exchanges, as in 1957 when the Dodgers invited Shigeru Mizuhara, manager of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants as well as two of his players, pitcher Sho Horiuchi and catcher Shigeru Fujio, to train at Dodgertown. On March 2, 1961, the entire Yomiuri Giants team arrived there for training. O’Malley even had dining room menus printed in Japanese for the occasion.

The successful Giants would return for instruction and spring training visits in 1967, 1971 and 1975 under O’Malley’s leadership. One of the most popular figures during these camps was Giants’ slugger and all-time home run leader . “We could see how togetherness came about through a well-organized program,” said Oh of the Dodgertown experience. “I saw that a veteran player should work harder. Some of the busiest workers among the Dodgers in camp are their most experienced men. Spring training should not only be physical preparation. It also should be mental readiness. It is obvious that victory comes from team play. This you can gain in a place like Dodgertown. It brings everyone together more.” Joe Hendrickson, Dodgertown

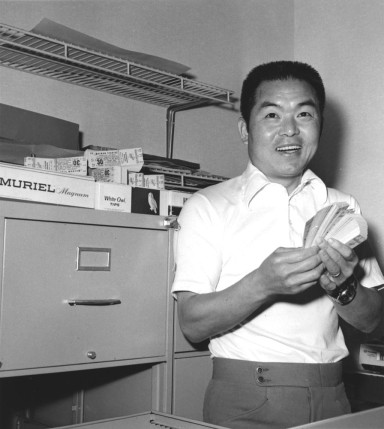

Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara became Assistant to President Peter O’Malley in 1982. He is shown at the Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida ticket office. Ikuhara worked closely with Peter O’Malley to develop international baseball friendships and the emergence of players from Asia to play in the major leagues. Ikuhara was elected to the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame in 2002.

In 1965, on the recommendation of Satoro Suzuki, the highly-respected sports columnist and emissary to Yomiuri, O’Malley hired Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara, a graduate of prestigious Waseda University in Tokyo, to work in various departments and learn the business of baseball. On the Dodgers’ second goodwill tour to Japan following their appearance in the 1966 World Series, the highly-educated and respected Ikuhara served as a team ambassador and interpreter. Years later, Ikuhara wrote two baseball books printed in Japanese (“The Man Who Survives the Race” in 1984; “A Winning Tradition” in 1985) and in summer of 2002 was posthumously honored with induction into the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame.

“We’ve brought the Japanese teams to the Dodgers’ spring training camp a number of times, and the Japanese are students of the game,” said O’Malley. “They work harder than our boys do in spring training. The Japanese (players) are out there at 8 in the morning and they are still out there at 6 at night. They work.” Ed Schoenfeld, The Sporting News, November 6, 1971

Dodgertown opened its arms to the world. In 1960, Kaoru Betto, a manager from Japan, attended Spring Training and traveled with the Dodgers for the entire season. In March, 1963, Boudewijn Maat, an outstanding amateur player, of Holland was invited to Vero Beach to study American methods of training and playing baseball. In 1965, the Dodgers invited Ricardo Garza, a top player from Mexico, to study and train at Vero Beach. Other exchanges from Cuba and Mexico took place.

The Dodgers branched out from their base to make some spring trips, including to Mexico for a three-game series in 1964. The Dodgers played before 75,000 fans in the games in Mexico City. Unfortunately, a few months later on May 31, Bud Holman died at his Blue Cypress ranch. The rancher, citrus grower, automobile dealer, airport terminal manager for Eastern Air Lines had been a good friend of the O’Malleys, Dodgertown and the entire Vero Beach community.

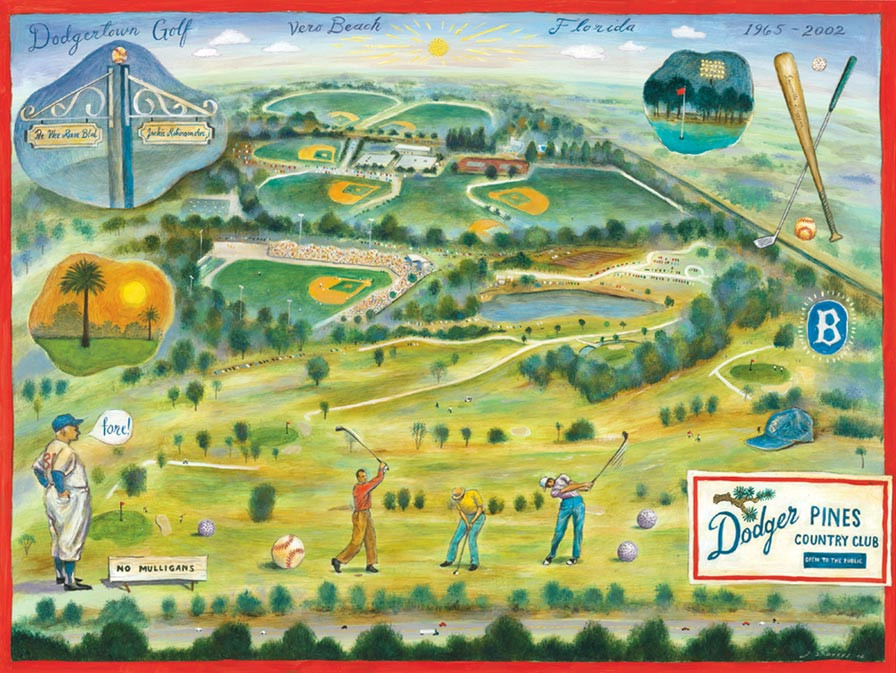

After baseball, one of Dodgertown’s most popular activities for players and executives alike was golf. Walter O’Malley built two golf courses on the Dodgertown property (a nine-hole course in 1965 and an 18-hole course in 1971). This John S. Dykes illustration celebrates the golfing fun at Dodgertown.

Golf Courses Privately Built

Under the purview of Director of Dodgertown Peter O’Malley, the Dodgers completed arrangements to purchase 110.4 acres of airport land, building and improvements for $133,087.50 from the city of Vero Beach, when final approval by the Federal Aviation Agency transpired on September 23, 1964. The agreement benefited the city’s general fund as the land would go on the tax rolls. The monies collected from the sale were to be “deposited in the Airport Fund for general aviation improvements and maintenance.” Three years prior, the city had guaranteed annual payments of $12,000 to the Airport Fund on behalf of the Dodger lease to satisfy the FAA which disagreed with the terms of the government’s original deed. William Jackson, Vero Beach Press-Journal, September 24, 1964 The city finalized arrangements for the Dodgers to become the only major league club in Florida to own their own spring training grounds on March 16, 1965, when O’Malley and Vice President and part-owner James Mulvey presented a check to Vero Mayor Jack D. Sturgis.

In succeeding years, the Dodgers were successful in purchasing additional acres (some 340 more) of Vero Beach land to expand the base of operations. Careful maintenance and use of the land made the Dodgers popular friends of the surrounding Vero Beach community.

In March 1954, Walter O’Malley designed and opened a makeshift nine-hole pitch and putt golf course. Kay O’Malley, holding the flag, is joined by (l-r) Elizabeth Hickey, Edna Praeger, Peg Thompson, May Smith and Lela Alston.

Still faced with racial prejudice in the South, O’Malley had African-American players who were unable to play golf in their free time at one of Vero Beach’s two private golf courses. In 1953, he had designed a makeshift nine-hole, pitch-and-putt golf course around the man-made lake with input from the players so that they could use it in spring, 1954. But with limited holes and space for that course, O’Malley decided to do what he felt was right — to build and maintain his own course, adjacent to Holman Stadium and the lake on the Dodgertown property. In 1965, he hired two minority coaches — African-American Jim Gilliam, a likeable former Dodger player and Preston Gomez of Cuban descent. The nine-hole course, named Dodgertown Golf Club, opened in 1965 and was available to the Dodger players, as well as the public. As an avid golfer himself, O’Malley could be found with Dodger players and executives on the links in his free time. To best aid his game, he personally oversaw the design of the course and the placement of its sand traps!

Two of O’Malley’s top competitors on the links were his good friends Dr. Jim Priestley, the internationally renowned surgeon at Mayo Clinic and Jim Mulvey, part-owner of the Dodgers and President of Samuel Goldwyn Productions in Los Angeles. As the boss and with a twinkle in his eye, he could get a bunker placed overnight to discourage these opponents.

“Those stories are true,” said Peter O’Malley. “For instance, Dr. Priestley would always kind of push his ball off to the right of the fairways, maybe 180, 200 yards. So my dad would think, ‘That would be a good place to put a trap.’ I remember one night when he did that. He called over the grounds guys and before you knew it they had the hoes out and sand, and the next day there was a trap.” Peter Kerasotis, Dodger Blues, Golf Journal Magazine, March/April 2002

O’Malley would take an early morning ride around the Dodgertown complex and say “Good Morning” to employees busily preparing for the business of the day. At each of the games, Kay O’Malley had her trusted official scorebook in which she kept score of every game.

Six years later, O’Malley expanded the golf interests of the Dodgers to include a piece of property adjacent to 43rd Avenue and 26th Street to an 18-hole course, called Safari Pines Country Club. The course featured a rare par-6 hole of nearly 667 yards. Subsequently, the name of the club was changed to Dodger Pines Country Club. In addition, 50 mobile homes were placed around the course, providing the Dodgers with a source of revenue to help offset the expenses of owning their own spring training camp.

O’Malley’s Dodgertown Vision

The first major league exhibition game played at night was on March 28, 1968 at Holman Stadium as the Dodgers faced the Chicago White Sox. Forty percent improvement on candlepower at the field, designed by Dodger engineer Ira Hoyt, made it possible to play. Of course, the many minor league teams could partake, as well. On November 20, 1968, Vice President Fresco Thompson passed away, six months after assuming the responsibilities of General Manager from Buzzie Bavasi, who left the Dodgers to join the expansion San Diego Padres as their first President. It was the first change of O’Malley’s lieutenants in 18 years. The following spring, longtime scout Al Campanis was the new Vice President, Player Personnel and Scouting and William P. Schweppe was named Vice President, Minor League Operations. In 1969, Dick Crago worked his first spring as the public address announcer at Holman Stadium, a position he held for decades. O’Malley purchased a restaurant near Dodgertown called “The Shed” and turned it into a dining establishment for players and the public known as “The Dodger Cafeteria,” which had a brief run.

Walter O’Malley and his son Peter O’Malley, June 4, 1978.

Los Angeles Times Collection, UCLA Library Special Collections

O’Malley’s son, Peter, became the Dodger President on March 17, 1970 at Dodgertown. The symbolic changing of the guard was an important crossroads for them, as the senior O’Malley moved to Dodger Chairman of the Board. It gave Peter an opportunity to carry the brunt of the workload, while his father continued to serve on the all-important Major League Baseball Executive Council, on other boards and maintain his many charitable interests.

In 1965, Capt. Lew Carlisle took over the reins as pilot from Capt. H.R. “Bump” Holman. In 1971, the Dodgers purchased a 720-B Fan Jet from American Airlines and christened it Kay O’II, the second Dodger-owned aircraft named for O’Malley’s wife, which would make frequent visits to Dodgertown to haul major and minor league teams to and from the training base. Capt. Carlisle and his wife Millie became instant favorites of the O’Malley family and the rest of the Dodger organization.

The O’Malleys worked on a major renovation of Dodgertown which took place in 1972. That year, 90 modern accommodations for the players, coaches, executives and press were placed on property which would replace the old barracks. O’Malley and his wife always resided in Number 162 on Sandy Koufax Lane located adjacent to the competition-size swimming pool.

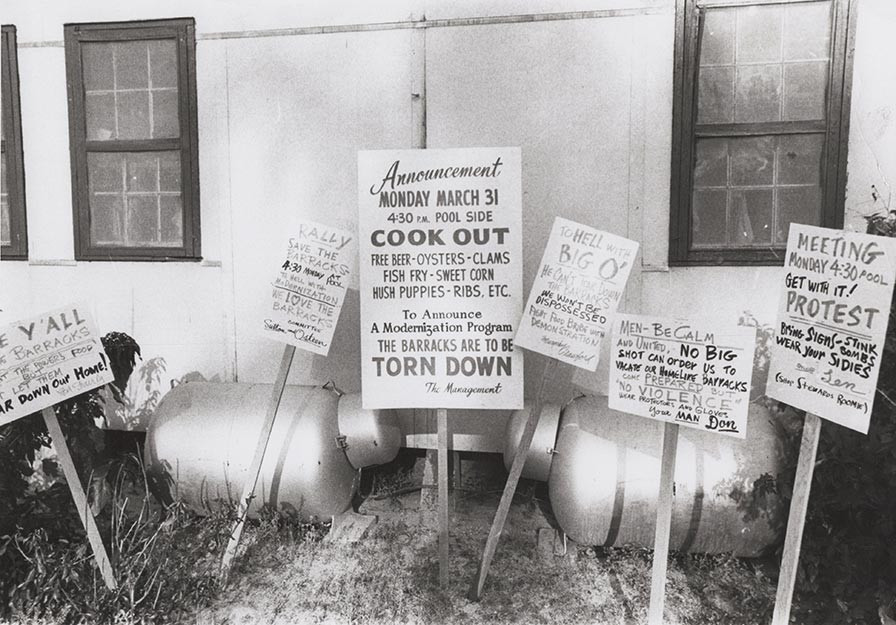

Despite a mock “Save the Barracks” campaign headed by O’Malley and ballplayers like Ron Fairly, Don Sutton and Claude Osteen in 1969 and 1970, the two old Naval barracks were eventually razed.

Tongue-in-cheek protest signs when it was announced the Naval Air Station barracks would be replaced by up-to-date accommodations for players, executives and staff to live at Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida. The Navy barracks had been in operation for World War II and had continuous use for players at Dodgertown through the 1971 season.

By 1974, the continuation of expansion included a 23,000-square foot administration building, which included the Major League clubhouse, medical department, dining room, kitchen, main lobby, broadcasting studio, photo darkroom, press room, lounge, training rooms, equipment room, minor league clubhouse and laundry room. In 1976, clubhouses were built for the two golf courses.

O’Malley’s vision of Dodgertown as a multifunctional and year-round destination was certainly taking shape when in 1977 he started the Dodgertown Conference Center and executed an agreement to have it managed by Harrison Conference Centers. This immediately brought corporate business seeking a top-notch place to hold important meetings, seminars and conventions. Attendees would live right on site, dine in the Dodgertown dining room and use the fields and competition-size swimming pool for recreational purposes. The Dodgers expanded their interests into other sports, as the National Football League New Orleans Saints initially utilized the camp to prepare for their championship season in 1974. Many more NFL teams would follow suit preparing for the playoffs.

Success Year-Round

Where once baseball training and teaching was the only business at Dodgertown for two months, the O’Malleys had several year-round features that were successful, including golf, football, the conference center, 70 acres of commercial citrus growing and real estate (50-unit housing development called Safari Pines Estates).

But as baseball goes, Dodgertown continued to be the initial proving ground for so many talented young players, including six National League Rookies of the Year under O’Malley’s reign, all looking to make a name for themselves and launch a career with the Dodgers.

After Walter O’Malley passed away on August 9, 1979, just 28 days following his wife Kay’s death, the Dodgers and Dodgertown continued to thrive and develop under son Peter’s administration. Mr. and Mrs. O’Malley missed the violent effects of Hurricane David which damaged the press box at Holman Stadium on September 3, 1979 and the first year of a Vero Beach Dodger team in the Florida State League in 1980. But, there was also time to remember the past. The tradition of an annual Memorial Mass, initiated by Kay O’Malley to commemorate those individuals who worked, or were guests, at Dodgertown through the years were remembered by name each spring. It was a way of honoring not only the memory of the departed and their contributions, but what Dodgertown has stood for since it came into existence in 1948; namely family. And perhaps, a little slice of heaven on earth.

DODGERTOWN’S DIRECTORS

Spencer Harris (1948-53)

Edgar Allen (1954-59)

Leon Hamilton (1960-61)

Chick Walmsley (1961)

Peter O’Malley (1962-65)

John Stanfill (1965)

Dick Bird (1965-1974)

Charlie Blaney (1974-87)

Terry Reynolds (1987-88)

Craig Callan (1988-2018)