Feature

Excerpts from “Forever Blue”

Introduction

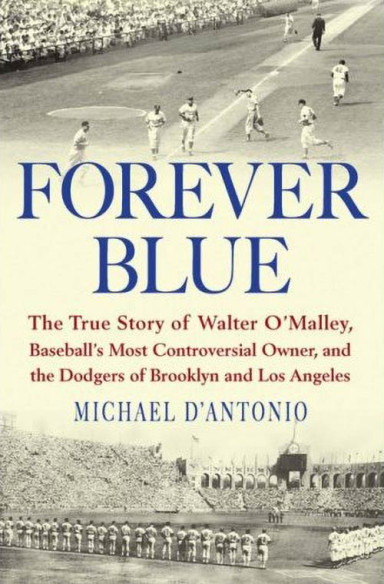

The following excerpts are from the 2009 book “Forever Blue,” a groundbreaking and comprehensive biography about former Dodger owner Walter O’Malley by Michael D’Antonio, who shared a Pulitzer Prize while reporting at Newsday.

The cover of “Forever Blue” by author Michael D’Antonio. The biography, published by Riverhead Books, details the life and career of Walter O’Malley.

D’Antonio delivers a compelling and inside look at O’Malley, shedding new light on the most significant baseball owner of the 20th Century. For an unprecedented 10 years, O’Malley searched for solutions to privately build a new stadium for the Dodgers in Brooklyn to replace aging Ebbets Field.

The complex portrait of O’Malley created by D’Antonio is made possible by his unfettered access to the vast O’Malley archive which includes 30,000 documents and artifacts, plus his own independent research and interviews. Working in files that have never been opened to any researcher, D’Antonio found handwritten letters from Jackie Robinson and a wide range of memorabilia—everything from a tiny and valuable Christy Mathewson baseball card, to contemporary records of key events (like O’Malley’s purchase of team stock), to a hand-written letter from Walter to his wife and son, which outlined the financing for building Dodger Stadium.

D’Antonio details the struggle with New York officials to assemble land for the stadium in Brooklyn, which O’Malley would have purchased. That eventually led to O’Malley’s decision to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

Michael D’Antonio

O’Malley’s legacy includes the historic expansion of Major League Baseball westward, bringing the Dodgers to Los Angeles for the 1958 season, making baseball truly national and privately building Dodger Stadium, the first and finest baseball ballpark of the modern era. Also presented are O’Malley’s countless challenges on two Coasts; the love of his life; the modernization of Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida including helping to design, build and privately finance Holman Stadium in 1953; and the successful organization he led that won four World Championships.

Two polls in December 1999 provide the backdrop for the significance of O’Malley’s career, as ABC Sports Century panel ranked him 8th in its Top 10 Most Influential People “Off the Field” in sports history, while The Sporting News named him the 11th “Most Powerful Person in Sports” in the 20th Century. In addition, O’Malley was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008, one of only 26 enshrined in the “Executives/Pioneers” in the game’s illustrious history.

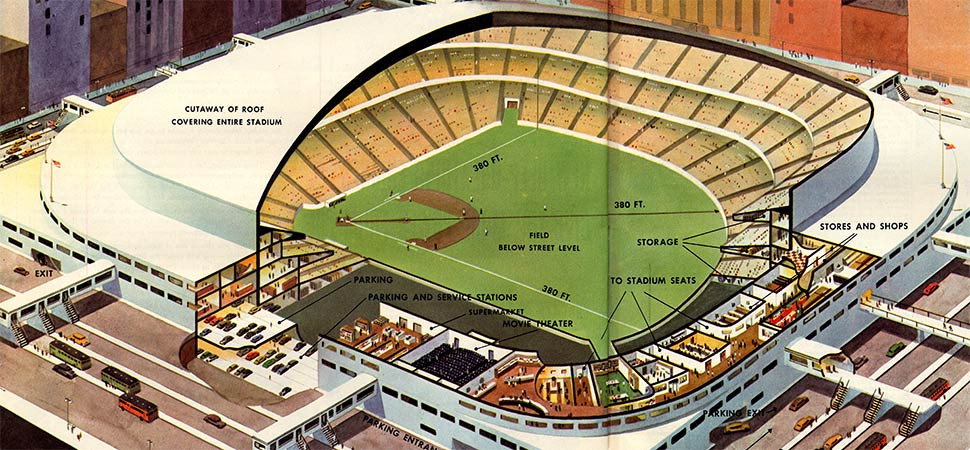

Colliers Magazine on Sept. 27, 1952 issue illustrated one of the Dodgers’ new ballpark proposals for Brooklyn.

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“California Calls” pgs. 164-166

In the summer of 1952, O’Malley helped a writer at Collier’s magazine put together an article about his concepts, developed with the help of Emil Praeger and Norman Bel Geddes, for just such a ballpark. Hyping “the future” was a staple for this magazine, which had recently devoted dozens of pages to space travel as conceived by Wernher Von Braun and others.

When published, O’Malley’s futuristic vision was a column-free, weatherproof dome – possibly movable or translucent – seating fifty-five thousand for baseball and ninety thousand for events like prizefights. The field, which could be made of artificial turf, would be lowered below ground level, and parking arranged so customers could walk from their cars to their comfortably cushioned seats without much of a climb. Plans for traffic would allow thirty thousand people to leave the park within fifteen minutes, but if they chose to linger they could shop in an arcade of stores or have their oil changed by attendants in the parking garage. (These services, along with office space and the garage, would be available for neighborhood use every day of the year.) Everywhere machines would replace workers by taking tickets, opening gates, and dispensing food.

Pressed for his most realistic view, O’Malley told Collier’s he believed that a stadium very much like the domed wonderland he described would be built eventually. Where and when were a different matter, he said, adding “We’ve already had too much of that wait-’til-next-year stuff in Brooklyn.”

It was an honest answer from an owner who couldn’t be sure that Brooklyn and the Dodgers would merit such an enormous investment. Still, a new park seemed essential if the club were to remain in the borough and thrive. And O’Malley was the type to keep every option open for as long as possible. In late 1952 he used a chance meeting with George Spargo, who worked on slum clearance under Robert Moses, to remind him of the benefits of a new Brooklyn ballpark. After many years with Moses, George Spargo had become one of the most powerful bureaucratic functionaries in New York. He did the gritty work of arranging rich contracts for politically important men who became Moses’s dependents. Spargo and Moses would have to be involved if the government was going to help the Dodgers but in a politically contentious place like New York City this wouldn’t happen quickly.

While he waited, O’Malley embarked on a bit of a practice run, building a little ballpark for Dodgertown so his team wouldn’t have to decamp for Miami for its spring training games. Impressed by the design of the new stadium in Miami, where no seats were blocked by pillars or posts, he had Emil Praeger work on a similar plan for Dodgertown. O’Malley was involved in every aspect of construction, right down to the specifications for the cypress planks that would be used for seating. He also chose to name the park for Bud Holman.

As might be expected, the stadium project met some opposition. The entire campsite was owned by a local government agency and leased for the ceremonial sum of $1 per year and the promise of increased tourism. Local critics often questioned the trade-off, alleging that the Dodgers got a sweetheart deal. O’Malley did respond at times. When he came under fire in 1952, he wrote to a banker in Vero to warn, “I do not know how to run away from a fight.” The critics backed off and the project went forward.

Emil Praeger needed less than a year to design and build the stadium, which became one of the most idyllic spots for baseball in the country. Gentle sloping walkways brought fans to the gate, and when they passed through they discovered a beautiful green diamond. Earth removed for construction was used to create berms that marked the limits of the outfield. Towering, graceful palm trees lined the perimeter of the entire property. Altogether the little park was a marvel of simplicity where spectators were almost as close to the action as parents at a Little League game.

When Holman Stadium opened on March 11, 1953, the visiting dignitaries included the governor of Florida and the president of U.S. Steel. They saw the Dodgers beat the Athletics, but O’Malley missed the game. After the opening ceremonies, he disappeared for a meeting with Commissioner Frick, other members of the major league executive council, and the owner of the Boston Braves, Lou Perini. At this private conference Perini discussed moving his team to Milwaukee. The Braves had suffered a shocking decline in attendance, going from one million in 1949 to less than three hundred thousand in 1952. Milwaukee beckoned with a new county stadium that would eventually hold more than fifty thousand.

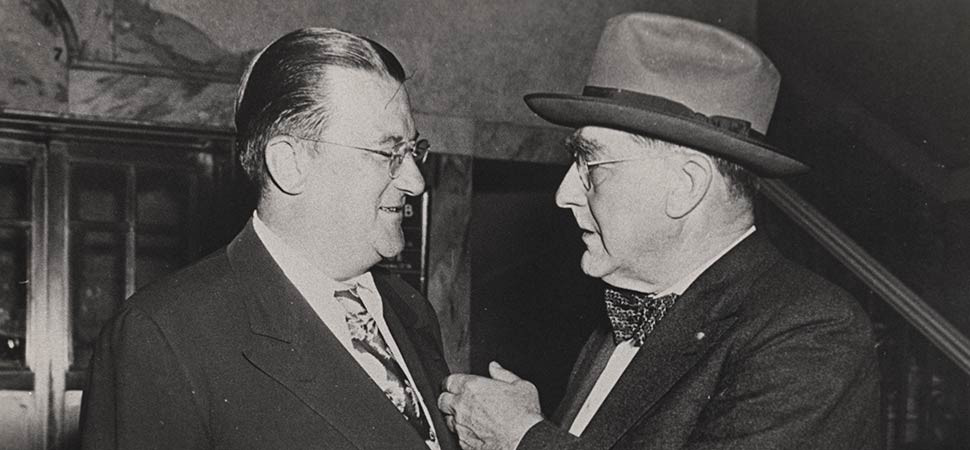

Walter O’Malley and Branch Rickey circa 1945.

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“Rickey, O’Malley, And Smith” pgs. 72-74

After World War I, gate receipts had bounced back smartly, but more importantly, except for the worst years of the Great Depression, attendance had grown more rapidly than the population. In 1920, 106 million Americans bought 96 million tickets. In 1940, 132 million people purchased 135 million tickets. It didn’t take much foresight to imagine that when the GI’s came home, married, and had children, the robust growth in population and baseball would resume. And since they weren’t making any more major league teams – the same sixteen had held a monopoly since the year O’Malley was born – fans would have no choice but to go to the same old ballparks and support the same old teams.

Sitting in the cat bird seat (one of Brooklyn broadcaster Red Barber’s favorite expressions), O’Malley saw that the team’s operation was becoming more rational and its finances more stable. He also understood baseball’s long-term potential. Still relatively young at age forty-one, he could anticipate being part of future glories. Others were not so sanguine. By early 1944, Edward McKeever’s heirs had endured nearly twenty years of boardroom squabbles, financial perils, and uneven play on the field. The big-league team had finished the previous year with just a small profit and on the first road trip of this new season lost ten out of fourteen games. Soon the Dodger’s goal became avoiding a last-place finish. No longer interested in waiting for what could be, Edward McKeever’s descendants notified team lawyer O’Malley that they wanted to sell their quarter interest in the team as soon as they could get a decent price.

The other owners had claims on stock as it became available and so O’Malley first consulted James Mulvey, whose wife, Marie, was the other McKeever daughter and thus controlled 25 percent of the club. The Mulveys weren’t interested in upping their stake. The fractious Ebbets heirs, who numbered more than twenty and owned half the club, were even less inclined toward buying. They wanted out of baseball entirely, but were still too mired in their own conflicts to make a deal. The most prominent among them, Charlie Ebbets Jr., had recently changed the complex family dynamic by dying in a Brooklyn boardinghouse and leaving two-thirds of his estate to a former housekeeper and one-third to his actual wife.

With the way clear of other bidders, and all the inside information he needed, O’Malley began to work on the deal that would set the course for the rest of his life. At a price of about $250,000, the McKeever block was too expensive for him to handle alone. But if he broke it into smaller pieces, then he could keep one for himself and get a seat on the board of directors. From this position it was possible that he could then buy out the Ebbets family, should they ever settle their differences.

Before he could carry out his big plan, O’Malley needed to find partners. He turned first to Andrew Schmitz, a longtime Dodgers fan who was Everett McCooey’s partner in an insurance firm. Schmitz agreed to participate in buying the 25 percent of the stock owned by the McKeever estate. O’Malley then approached Branch Rickey with the offer he had waited a lifetime to hear.

With only sixteen teams in the entire country, the fraternity of major league owners was small, and despite his efforts to join, Rickey had been excluded for forty years. This time he was invited into an owners group eager for his baseball credentials. Rickey didn’t have any money to put into the deal. In fact, he was $300,000 in debt and so short on assets that he had borrowed on his life insurance. No problem, said O’Malley: he could arrange financing. It would have to be nearly total, said Rickey. “We’re prepared to carry you,” answered O’Malley.

The “we” O’Malley mentioned included the Brooklyn Trust Company, which would supply much if not all of the actual cash paid to the McKeever group. George V. McLaughlin’s (Brooklyn Trust) bank was having a record year and had recently raised its dividend by 15 percent. He could expect that the Dodger loans would be repaid through postwar revenues, and with the McKeevers out, McLaughlin would expect to see a friendlier face – Walter O’Malley’s – on the board of directors.

The stock sale was completed six weeks after the end of the season. It was announced with just the slightest bit of fanfare – a brief press conference where O’Malley and Schmitz presented themselves as “Brooklyn boys” who were determined to keep ownership “in Brooklyn, where it belongs,” said Schmitz.

This assurance was genuine. Rickey enjoyed unqualified support from Schmitz and O’Malley. Rickey got further backing a few months later when Schmitz was replaced by a new owner, John L. Smith, the president of Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, a Brooklyn company.

By the summer of 1945 those who followed the team closely understood that the O’Malley ownership group had their eyes on the Ebbets shares, too. Now on the board of directors, where he acted as secretary, O’Malley began negotiations to purchase them. The other side was represented by George V. McLaughlin and two of the Ebbets heirs, Joseph A. Gilleaudeau and Grace Slade Ebbets. Their goal was a price that would allow everyone with a claim to the original estate enough cash to end disputes that had raged in the courts since 1925.

Although George the Fifth had been O’Malley’s mentor and ally he didn’t make it easy. He and the other negotiators turned down offers staked at the price paid for the McKeever shares, holding out for a premium. At one point, six months passed without much progress. The two men saw each other often, and even went to see some boxing matches in early March, but the negotiations remained deadlocked.

McLaughlin had no reason to rush. Charles Ebbets had been dead twenty years. What were a few months more? McLaughlin also had plenty of other work to occupy his time. The bank was growing, and as a commissioner of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which was headed by Robert Moses, he was deeply involved in a massive program of bridge, tunnel, and parkway construction. McLaughlin could wait for O’Malley and company to meet his terms for the Dodgers stock.

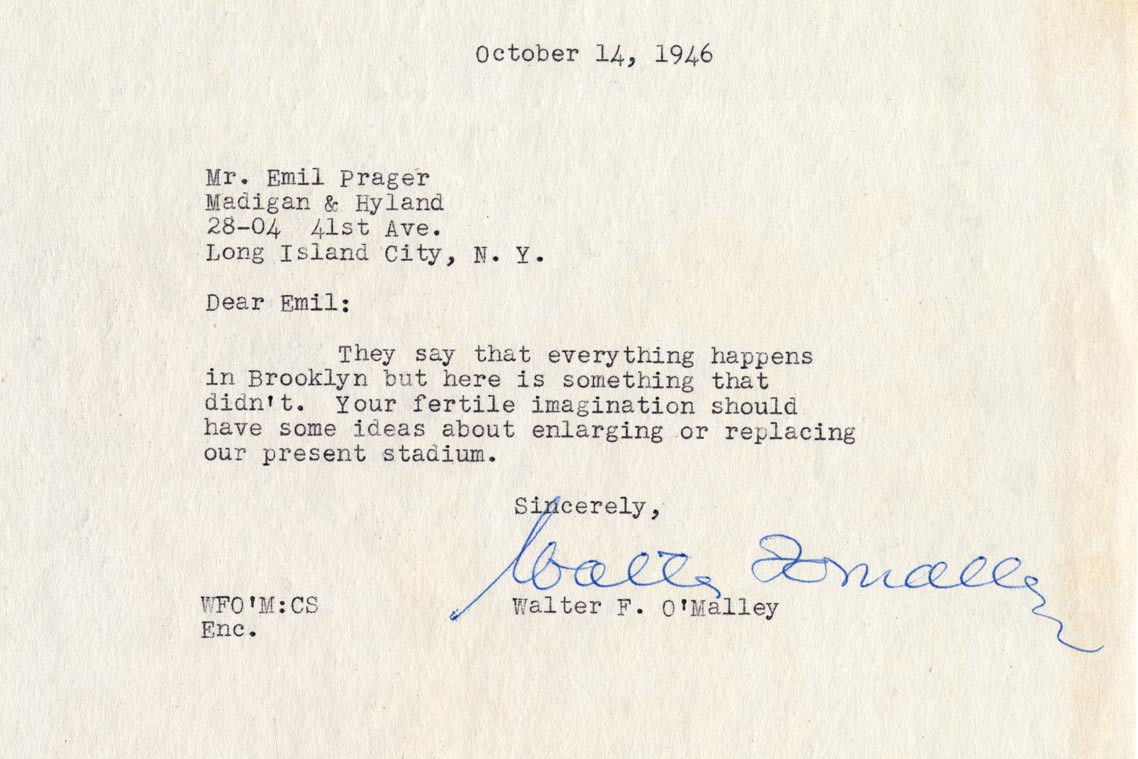

Letter from Walter O’Malley to Emil Praeger

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“Rickey, O’Malley, And Smith” pgs. 90-93

The future was on O’Malley’s mind as he tried to plot the Dodgers’ fortunes. He negotiated higher payments from advertisers who wanted space on the walls at Ebbets Field and time on the Dodger radio broadcasts. O’Malley also got involved with the nuts and bolts of putting on the games, including contracts with vendors and maintenance at Ebbets Field. When he reviewed the condition of the ballpark, he discovered that many important repairs and renovation projects had been delayed as, from one year to a next, crews chose to get by with a little scrubbing and a coat of fresh paint.

Not that paint came cheap. It cost a minimum of $30,000 each year to pay for the labor and paint required to spruce up the interior of the park. Fixing public walkways, worn and cracked by millions of footsteps, would cost nearly as much. And these figures paled when compared with fixing the toilets. In 1946 the estimate for this job, which was a matter of public health as well as convenience, was $100,000.

Conditions at Ebbets had been bad for years. Periodically, visits by various city inspectors had required the team to make emergency fixes to avoid losing the occupancy permit for the stadium. The electrical system, taxed by the addition of lights for night games, was especially troublesome…Many other parks built in the same period, including Tiger Stadium, Braves Field, and Wrigley Field, were kept alive in the same way. But nothing could be done about the biggest problem at Ebbets: the lack of space.

The stadium in Brooklyn was constrained by its small lot, which was wedged into a congested neighborhood. Other older parks had been expanded to seat as many as forty-six thousand (Comiskey Park in Chicago), but Ebbets remained stuck at thirty-two thousand, the smallest capacity in the National League. In both major leagues only Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., host of the American League Senators, was smaller. A full house in Washington was twenty-nine thousand, but with the Senators finishing no higher than sixth for eight straight seasons, demand for those seats was not great. Even in 1946, when they climbed to fourth, attendance fell below the league average.

In Brooklyn, where big games now drew more people than the stadium could hold, every fan who walked away represented lost revenue. This loss was made more evident by the fact that the Yankees could seat sixty-seven thousand and the Giants could get more than more than fifty-four thousand into the Polo Grounds. Often the Giants’ biggest gates in a season came on the days when the Dodgers visited. The execs on Montague Street could only dream of welcoming so many paying fans and selling them beer and pop and hot dogs and peanuts along with a game. Not one to abandon his dreams, in the summer of ’46 Walter O’Malley brought the now-famous engineer Emil Praeger to look at the house that Ebbets and the McKeevers built. A favorite of the regional development czar Robert Moses, Praeger was an expert in structural engineering who had also worked on parks and highways. He was known to the general public for designing New York parks and wartime engineering exploits, including the rapid construction of a protected harbor at Normandy during the D-Day invasion. At Ebbets, Praeger found a problem that defied an easy long-term fix. A big investment in renovations might make all the toilets flush and the wiring safe, but given the structure and the location, a significant expansion to create more seating was out of the question.

Even if a way could be found to add thousands of seats, the Dodgers would still face a second big problem: no parking. Designed and built long before the car culture took hold, Ebbets was served by just a few small lots that could handle six or seven hundred cars. With the war just months in the past, it was already obvious that America’s future was coming on four wheels. Auto production rose from about seventeen thousand cars in February 1946 to more than eighty-five thousand in September. And with William J. Levitt and others building thousands of new homes on Long Island, it was also clear that many of those cars would be kept in the suburbs by young war veterans – Dodgers fans – who were moving out to start families. If Ebbets was cramped and run-down, or it was impossible to park, why would they come to Brooklyn for a game?

The answer – they wouldn’t – was obvious to Walter O’Malley, and so was the solution. On October 14, 1946, he wrote Emil Praeger to suggest he apply his “fertile imagination” to the matter of “enlarging or replacing our present stadium.” A week later he made a report to the board of directors, raising for the first time the possibility of a modern new play space for the team and its fans. The issue was set aside, but O’Malley wasn’t going to let go of it.

At age forty-three, O’Malley could be expected to look further into the future than Rickey, who was sixty-five, and Smith, who was fifty-seven. He could imagine being active in the game for decades more, and would not accept second-class performance. However, a shabby ballpark with inadequate parking would hurt ticket sales and revenues. Without revenues the team couldn’t pay star players and risked succumbing to a cycle of losing on the field and at the box office.

As a young man, O’Malley was also more sensitive to the change promised by the new mass medium of television. In 1945 the chief engineer at General Electric foresaw a billion-dollar industry. However, as of 1946 the pioneers of TV had not yet figured out how to make it pay. At the time, almost every broadcast minute was being produced as original content by individual stations. This made the cost of programming extremely high. At the same time, advertisers who couldn’t be sure about the size of their audience were reluctant to pay much for commercials.

One obvious exception to this problem of high production costs and unreliable audiences was baseball. Every big-league team in America was already producing seventy-seven home games per year. Add cameras and a bit of narration and these games became television dramas, complete with heroes and villains and endlessly varying stories. Given the relatively low cost of production and baseball’s great appeal, it seemed a perfect fit for the medium, the teams, and sponsors.

Although O’Malley saw the opportunity, the Yankees seized it first, selling the rights to broadcast every Bronx home game in 1947 for $75,000 to the Dumont Television Network. After meeting with the other networks in New York, O’Malley zeroed in on CBS, meeting frequently with executives and sportscaster Bob Edge.

For O’Malley, this duty was not a hardship. It brought him into the exciting world of a new medium at a time when it was controlled by a handful of people. (Thanks to a demonstration put on by CBS, O’Malley and his co-owner Smith were among the first in New York to see color television.) In the end, O’Malley came up with a three-year arrangement for somewhat less than the Yankees received but nevertheless got the Dodgers onto the airwaves in 1947. At the same time the Giants went with NBC.

No one knew the effect TV might have on pro teams. Despite the money they got for broadcasting rights, many owners had worried when radio arrived because they thought people who could hear the games for free would stop coming to the ballpark. But no loss of attendance was ever noted, and it was quite possible that broadcasts of the games, especially reports that were as vivid and warm as Red Barber’s, actually expanded the team’s audience and enticed more people to come to games from greater distances. Optimists believed that television might also lure more people to the ballpark. Pessimists feared that since it provided a live picture of events, it might actually make people feel as though they didn’t have to see the game in person to experience it fully.

If television suppressed attendance, owners would have to find some way – advertising, higher rights fees, or special subscription-only broadcasts – to wring money of this new machine. In the meantime they would go ahead with the experiment. The timing of baseball’s arrival on TV was perfect for the fans in New York, because the game was about to begin the most exciting decade it would ever know.

Los Angeles City Councilmember Rosalind Wiener Wyman at age 22 was the individual most responsible for encouraging Walter O’Malley and the Dodgers to relocate. Here in council chambers, she reviews the potential land use for Dodger Stadium at a March 14, 1958 Dodgers hearing.

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“Wow! Wow! Wow!” pgs. 192-194

Baseball was becoming such a big issue in Los Angeles that even the most unlikely political candidate could use it to great advantage. Rosalind Wiener (soon to marry and take the name Wyman) had been raised by parents who displayed FDR posters in their drugstore. At eighteen she was Helen Douglas’s driver during the Senate race she lost as Richard Nixon smeared her with the charge that she aided Communists. Undiscouraged, she threw herself into the 1952 Stevenson campaign for president – another loss – and then put herself up for city council. (Besides baseball, her issues included bringing museums to the city and a proposed ban on the sale of horror comics in places where young children could see them.) She was all of twenty-two years-old.

The Wyman council campaign of 1953 was a months-long display of earnest door-to-door effort headquartered on the dining room table at her parents’ house. Weekends brought young Democrats from all over the state to work as volunteers. They stuffed envelopes and made phone calls, taking breaks only to eat and catch I Love Lucy on TV. Every weekday Wyman walked five miles or more, determined to meet every voter in her district. Her main publicity piece, a card listing her priorities, emphasized boosting the city with new cultural institutions and baseball. When she received a donation of several thousand bars of soap, these were given away with some sentiment about cleaning up local government.

On election night, Wyman’s campaign team listened for the results on the radio and heard the announcer say something under his breath. As Wyman would recall it was “Stop handing me these reports that say Miss Wiener is winning. They can’t be right.”

The reports from the precincts were correct. Miss Wiener did win, becoming the youngest person ever elected to the council. The next year she was part of a majority on the council who approved a resolution urging every city, county, and state agency to cooperate in every way possible in order to bring a major league team to the city. Every club in the country received a copy of the documents. The one sent to Brooklyn landed on Walter O’Malley’s desk.

Between the Los Angeles City Council’s correspondence, Bill Veeck’s two thick reports, and press accounts about the buzz over baseball in the West, Walter O’Malley was fully aware of the opportunity available in California. But in addition to these documents, which every owner in the league possessed, O’Malley also had constant contacts – letters, telegrams, phone calls – from Vincent X. Flaherty, Los Angeles Examiner columnist, baseball fanatic, and ceaseless promoter.

In one letter after another Flaherty tried to persuade O’Malley to either move the team to Los Angeles or sell it to someone who would. Although O’Malley often ignored him, Flaherty kept pitching with a combination of flattery, promises, and warnings that “someday you’ll realize” what a “wonderful opportunity” awaits. At one point in the summer of 1954, O’Malley finally responded with a long letter explaining the Dodgers’ situation in great detail and outlining his views on a business that seemed poised for big changes.

The way O’Malley saw it, the recent purchase of the St. Louis Cardinals by the beer giant Anheuser-Busch heralded a new era of corporate investment in the old game. A number of big corporations – including another brewery, a distillery, and an auto manufacturer – were trying to buy teams, said O’Malley, and Wall Street “lads” were “working their slide rules overtime” to figure out deals that combined pay television systems and ball clubs in one entity. Everyone, it seemed, saw great potential in a sport with momentarily depressed revenues but great long-term growth potential.

As owners of one of the strongest teams, O’Malley and his minor partners had already turned down a $6.5 million offer from a serious and well-qualified bidder. The decision was based on both the team’s potential and an estimated $10 million value for the franchise, its players, and real estate holdings scattered from Montreal to Vero Beach.

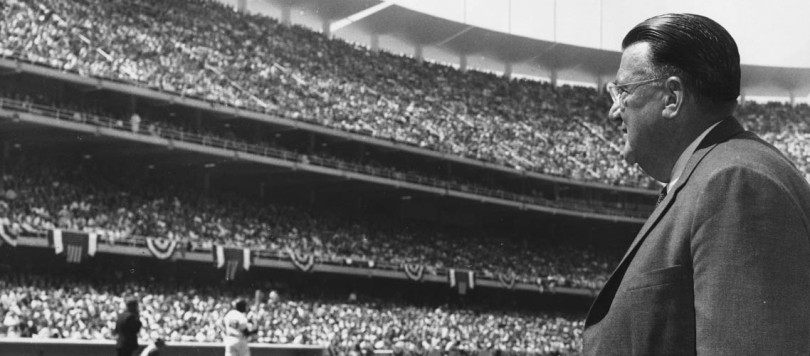

Vin Scully interviews Walter O’Malley at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, FL. O’Malley once responded to the question, “Who is the greatest Dodger?” by replying, “It’s Scully.”

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“The Battle of Chavez Ravine” pgs. 273-274

The Dodgers’ success was based in part on novelty but it was also built on the voice of broadcaster Vin Scully, whom O’Malley brought to Los Angeles from Brooklyn. O’Malley had been encouraged to hire a local announcer, but he had confidence in Scully. Before the season began, the two men discussed the tone of the broadcasts and O’Malley wondered, “Don’t you think you ought to root for the team?”

“I was trained to go down the middle,” answered Scully.

“I appreciate that,” answered O’Malley. “That’s what the people like here, so you stick with it.”

From opening day Scully served as a reliable guide to the game’s nuances, characters, and history. He taught millions who listened in cars, homes, and workplaces, to appreciate good play and strategy. Dogged in his pregame research, he always had a tidbit to tell about a player coming up to bat and an anecdote about the relief pitcher warming up in the bullpen.

Because most Dodgers away games were played in later time zones, Scully had a huge audience of commuters who tuned in on the drive home from work to catch the first innings of night games played in the Midwest or East. Drivers became so enraptured that when they got to their homes they remained in their cars until the end of an inning. Others raced inside to switch on radios that played through the dinner hour. All across Southern California, the genial Scully became a virtual guest in dining rooms and kitchens.

Scully had his greatest effect on fans in the stadium who brought transistor radios – a rather recent invention – and listened as he narrated the game they were watching. While most knew the stars on the field, Scully helped them to know every player and to grasp the flow of the game. The sound from thousands of tiny speakers could be heard by players on the field and feedback “gave the engineers fits,” he would later recall. And all the eyewitnesses put extra pressure on Scully to be accurate. He quickly grew comfortable with the relationship and sometimes played with the crowd. Once he organized them to shout “Happy Birthday” to an umpire at the end of an inning.

The bond Scully created with Los Angeles fans helped them to make the Dodgers their own, even though they arrived with a deep history. The connection also helped the broadcaster through a tough year and the first losing season in his Dodger broadcasting career. “We had a choice to come out with fresh new faces or the old familiar team that people had heard about,” said Scully. “We came out with that recognizable team, but a lot of them turned out to be over the hill. Still, the people supported us. And I never saw Mr. O’Malley really discouraged. Instead I could see his mind working all the time, working on the solutions to the problems.”

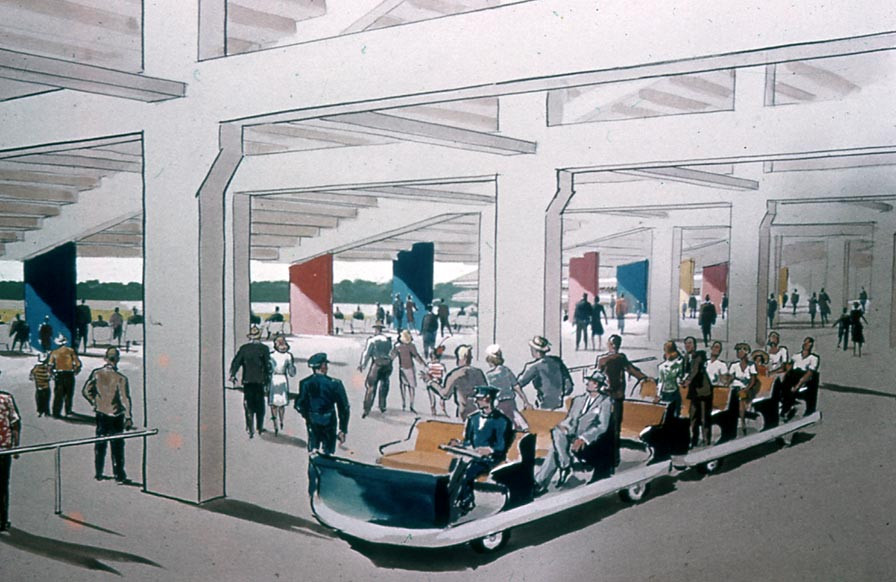

Early concepts of the new Dodger Stadium included ways to shuttle fans from the parking lots to their seats.

Copyright © 2009 Michael D'Antonio and Riverhead Books

“El Dorado” pgs. 287-88

As the money poured out, O’Malley obsessed over the Dodger Stadium project, continually scanning reports on every aspect of design and construction and making decisions on every key element. He wanted the best quality at the best price and dug for the information that would help him get it. The purchase of seats – he needed more then fifty thousand of them -- was a case in point. The American Seating Company began by asking for $16 apiece. When company officials met with O’Malley the price came down to $14.95. He then spoke to Horace Stoneham and learned that the city of San Francisco had paid $12.50 for regular seats and a dollar more for bigger ones to put in expensive boxes. Stoneham warned O’Malley that the contractor in San Francisco had promised to keep the price break secret, but O’Malley was able to use the information to save more than $100,000.

When he couldn’t get answers himself, O’Malley jotted questions on slips of paper and passed them to Dick Walsh, the team executive he had made his lead man on the job. He also ordered countless modifications and additions to make the stadium fit his vision. Some of his pet concepts, like a dining room named after Room 40 in the Hotel Bossert, were sentimental. Others, like two-person “love seats” for fans, were copied from Disneyland. A few were self-indulgent. O’Malley gave himself a big glassed-in office above the third base line and a private box for twenty-four.

The memos and scratch-pad jottings O’Malley left behind from this period reveal dozens of ideas that were considered and then rejected as impractical or outside building codes and city regulations. Among them were:

a residence atop the stadium

a compressed-air system to make Old Glory wave continuously on a tall flagpole

a water tower shaped like a baseball that would be lighted in different shades

during games, depending on whether the team was winning or losing *twenty-five-cent trams to bring patrons from parking lots to the entrances

water and light shows made by fountains matched with colored spotlights

a huge statue – a tripod of bats topped by a baseball – that could be seen from ten miles away.

These ideas and others reveal the same showman’s instinct that had prompted O’Malley to hire a clown for Ebbets Field. However, many of them clashed with the basic design philosophy he had worked out with Emil Praeger, which called for a more graceful style. Built almost entirely out of smooth concrete, the stadium was to be nestled into the ravine in a way that would allow people to park their cars in adjacent lots, enter the building, and find their seats with the fewest possible steps. Once inside, they would find that each one of the fifty-two thousand seats had an unobstructed view of the field. Refreshment stands and restrooms – forty-eight in all – would be close at hand.

Besides these conveniences, O’Malley insisted that the ballpark be beautiful to look at. He wanted none of the cold darkness that could be found at traditional stadiums in the East and Midwest. Built for families who would arrive by car from every direction on the compass, Dodger Stadium – that’s what it would be called – was to be bright, open, and a cheerful as Disneyland. And he wanted it built to last.

The concrete elements of the stadium were made with more cement, and thus were sturdier, than the state of California required for bridges and roadways. All of the twenty-five thousand concrete parts, some weighing as much as thirty-two tons, were cast on the site. They were then numbered and placed in orderly rows on the ground. While this work proceeded, earthmovers leveled a three-hundred-foot-high hill and used the earth to fill parts of the ravine.

In order to place the concrete sections together, Praeger and the main contractor, a local company called Vinnell Constructors, had to import a crane from Germany that, once assembled, would be the largest at work in North America. The monstrous machine was set inside the stadium where it picked pieces of the structure off the ground, swung them around, and then hoisted them into place. It was dangerous work and the derrick collapsed twice during the project, causing extensive damage both times and halting work.

Delays cost money and financing the burden became a big challenge. A group of four local banks had agreed to lend O’Malley $8 million, but by the middle of 1960 he discovered they wanted to charge a higher interest rate than they first offered and add fees equal to 1 percent of the loan. “This increase over our budget would, of course, be financially fatal,” he wrote in a letter to his wife and son…

The option that saved O’Malley materialized when he met with Reese Taylor, head of locally based Union Oil. Union Oil had $27 million in profits the previous year and was on track to make even more in 1960. Taylor, who had long been involved in the “Bring baseball to Los Angeles” drive, wanted to buy the rights to the team’s radio broadcasts. He was prepared to pay $1 million per year for eight years.

O’Malley proposed instead a more substantial arrangement. He asked that Union Oil act as his prime construction financier, lending the Dodgers $8 million at a lower rate than the bankers had requested. (For the first two years O’Malley would make no payments and the interest rate would be zero.) In exchange he’d let Taylor pay $1 million per year for the broadcast rights for ten years, not eight. As an added incentive, he would give Union Oil exclusive rights to advertising inside the stadium and a concession for a gas station to be built in the parking lot.

Between the grace period and all the cash that Union Oil would pay for radio rights, O’Malley saw this arrangement as a “self-liquidating” loan. No banker would ever accept such terms. But Reese Taylor, apparently smitten with the idea of Union Oil being connected with the Dodgers, saw an opportunity. After action by the oil company’s board of directors, the money that would make O’Malley’s dream stadium was deposited in a Dodger account.

*

O’Malley’s ballpark was going to be different from the Coliseum in almost every way. It would have a perfectly symmetrical playing surface, with the right- and left-field corners both 330 feet from home plate, which was set in the west end of the park so the sun would have a minimal effect on batters or fielders. Seats would be available on six levels, and many of the spectators would be shielded from the sun by upper decks and a wavy roof at the very rim of the stadium. Most would also get a pretty view of either downtown Los Angeles or the distant San Gabriel Mountains.

The outline of this baseball paradise was easy to see once the shape of the stadium was carved out and Vinnell began to put the concrete pieces together. At sunset a visitor could stand above the field level, behind where home plate would be, and watch the sky behind the mountains turn pink, orange, and deep purple. Cool air filtered in from nearby canyons and chased away the heat of the day. The sight of the work in progress thrilled O’Malley, who wrote to his old friend Frank Schroth (former publisher, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and editor, The New York News) to describe watching “the dream come true.”