Feature

Unprecedented 10-Year Effort to Keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn

Summary

In 1946, Walter O’Malley began his quest to find a solution for aging Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Parking at Ebbets Field was limited to just 700 cars in the scattered lots around the ballpark. In 1912, in Leslie’s, The People’s Weekly, Dodger owner Charles Ebbets wrote, “I want to build a structure that will fill all demands upon it for the next thirty years.” “Why I Am Building a Baseball Stadium”, Charles Ebbets, President Brooklyn Baseball Club, Leslie’s, The People’s Weekly, April 4, 1912 Coincidentally, that would take the steel, brick and cement stadium to the end of its life expectancy at about the time O’Malley started searching for solutions.

O’Malley wanted to privately finance, design, build and maintain a new stadium for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. He was seeking assistance in assembling land, which he would pay for, in order to privately build a dome stadium at his preferred location at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues. On October 14, 1946, O’Malley writes a letter to renowned designer-engineer Captain Emil Praeger of Madigan & Hyland in Long Island City, New York, “Your fertile imagination should have some ideas about enlarging or replacing our present stadium (Ebbets Field).” O’Malley archive, Walter O’Malley letter (copy) to Capt. Emil Praeger, October 14, 1946 However, after a study completed by designer Norman Bel Geddes in 1948, it was determined that renovating Ebbets Field made neither economic nor practical sense, as parking would still be lacking.

O’Malley repeatedly appealed to New York City’s powerful Robert Moses, who was Parks Commissioner for the City of New York, among his many titles and he wielded control over parks, bridges, highways and construction projects. O’Malley wrote to Moses on June 18, 1953, “My problem is to get a new ball park – one well located and with ample parking accommodations. This is a must if we are to keep our franchise in Brooklyn.” O’Malley archive, Walter O’Malley letter (copy) to Hon. Robert Moses, June 18, 1953 That day, he wrote to George V. McLaughlin, President of the Brooklyn Trust Company, which held the mortgage to Ebbets Field, “We need a new ball park. It should be privately built and maintained. The Milwaukee story (County-owned ballpark) is an interesting one but I would prefer to exploit the possibility of private ownership.” O’Malley archive, Walter O’Malley letter (copy) to Hon. George V. McLaughlin, June 18, 1953 And a week later in a letter to William Tracy, Vice Chairman, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, O’Malley states: “It is my belief that a new ball park should be built, financed and owned by the ball club. It should occupy land on the tax roll...The only assistance I am looking for is in the assembling of a suitable plot and I hope the mechanics of Title I (of the 1949 Housing Act) could be used if the ball park were also to be used as a parking garage.” O’Malley archive, Walter O’Malley letter (copy) to William J. Tracy, June 25, 1953

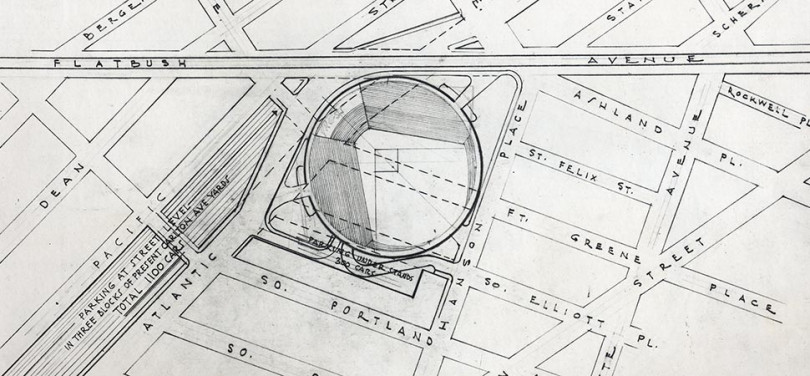

While at least 10 potential stadium sites were considered, O’Malley preferred the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues because all modes of transportation converged there, including nine subway lines and the terminal of the Long Island Railroad. The translucent dome stadium that O’Malley envisioned led to discussing its feasibility with some of the greatest architectural designers and minds of the 20th Century: Bel Geddes, Buckminster Fuller and Eero Saarinen. Several models were made and all determined it was absolutely possible in the heart of Brooklyn. O’Malley wrote Fuller, “I am not interested in just building another baseball park.” O’Malley archive, Walter O’Malley letter (copy) to Buckminster Fuller, May 26, 1955

As the 10-year effort went forward, O’Malley worked with New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, a government-created Brooklyn Sports Center Authority signed into law in Brooklyn by New York Governor Averell Harriman and, of course, Moses. With dwindling attendance at Ebbets Field and the Milwaukee Braves’ ascent in attendance and success on the field, O’Malley took action on several fronts. He played some home games in 1956 and 1957 at Jersey City, New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium. He sold Ebbets Field in the fall of 1956 and arranged to lease it back for three years (plus two option years through 1961) until a new stadium could be built and he sold his ballpark in Montreal (Triple-A) to raise capital for land and construction costs for a new stadium.

When it was evident that the only site that Moses was willing to recommend was in Flushing Meadows, Queens, O’Malley had to consider leaving Brooklyn for that site and weighing that against other options. Only when acquiring land at his preferred site in Brooklyn was no longer a possibility did O’Malley consider Los Angeles as an option. O’Malley had been in Los Angeles on just three brief occasions. For many years, Los Angeles desired to become a “big league” city in sports and was vigorously trying to attract a Major League Baseball team. In May 1957, the National League gave unanimous consent for the Dodgers and the New York Giants to move to Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively, but the two clubs had to move together before October 1, 1957.

Horace Stoneham and the Giants announced they were moving to San Francisco on August 19, 1957. O’Malley fought to the end to try to remain in Brooklyn. On October 8, 1957, it was announced that the Dodgers were going to relocate to Los Angeles.

Timeline

Beginning in 1946, Dodger owner Walter O’Malley’s sole focus was to find a solution to aging Ebbets Field and to keep the Dodgers playing in a new stadium located in Brooklyn.

During his unprecedented 10-year effort to remain in Brooklyn and to privately build a new stadium for the Dodgers to replace Ebbets Field and its limited parking for 700 cars, O’Malley stated repeatedly that he was not asking the city to build him a new stadium. He was seeking assistance in assembling land, which he would pay for, in order to privately build a new ballpark – a domed stadium – at his preferred location at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues in Brooklyn.

On October 14, 1946, O’Malley writes a letter to renowned designer-engineer Capt. Emil Praeger of Madigan & Hyland in Long Island City, New York stating, “Your fertile imagination should have some ideas about enlarging or replacing our present stadium (Ebbets Field).” However, after a study was completed by designer Norman Bel Geddes in 1948, it was determined that renovating Ebbets Field made neither economic nor practical sense, since parking would still be lacking.

On June 18, 1953, O’Malley writes to Robert Moses, powerful Parks Commissioner for the City of New York, “My problem is to get a new ball park — one well located and with ample parking accommodations. This is a must if we are to keep our franchise in Brooklyn.”

That same day, O’Malley writes George V. McLaughlin, President of the Brooklyn Trust Company: “Be good enough to let me have the benefit of your thoughts on the following: I would also like to talk the problem out with Bob Moses. We need a new ball park. It should be privately built and maintained. The Milwaukee story (County-owned stadium) is an interesting one but I would prefer to exploit the possibility of private ownership.”

On June 25, 1953, O’Malley writes William Tracy, Vice Chairman, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, a letter stating, “It is my belief that a new ball park should be built, financed and owned by the ball club. It should occupy land on the tax roll. That is the impression I meant to convey in the second paragraph of my letter where I stated -- I would prefer to exploit the possibility of private ownership. The only assistance I am looking for is in the assembling of a suitable plot and I hoped the mechanics of Title I could be used if the ball park were also to be used as a parking garage.”

More than 10 potential stadium sites were considered before O’Malley concentrated on the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues. He preferred this site as all modes of transportation converged there, including subways and the Long Island Railroad. An outdated meat market was on the site, in a congested area in need of rehabilitation, which the domed stadium with plentiful parking would have provided.

On May 24, 1954, O’Malley shows his disapproval of a new five percent admissions tax to be placed on tickets sold at Ebbets Field and warns the tax on amusements would be adverse to the city’s interests. O’Malley’s telegram to New York City Mayor Robert Wagner stated, “You should not do anything to force baseball (from New York) to other cities. You know what the municipal authorities of Baltimore and Milwaukee have done to attract and maintain major league franchises. Los Angeles, Dallas, Havana, Montreal, Toronto, Kansas City and the twin cities of St. Paul-Minneapolis are ready to put money on the barrel head to get a major league baseball franchise. Against this competition our city is going in reverse.” Despite his plea, the plan passed on tickets to all New York amusements, costing the Dodgers $165,000 annually.

On December 27, 1954, O’Malley writes in a letter to Frank Schroth, publisher of The Brooklyn Eagle, “The only government assistance I want is in its power to assemble a site which we will buy and on which we will build and maintain a stadium…I really feel that I have been quite clear that we do not expect the government to finance and own our proposed new stadium.”

On December 28, 1954, Schroth replies to O’Malley, “For a couple of years now we have been talking over the possibility of the Dodgers getting a new stadium. After the first meeting or two with Moses and Cashmore, it was impressed upon everybody that government money could not be put in that sort of development. You have always made it crystal clear that all you wanted was for the city to use its power to assemble a site – perhaps in connection with a well rounded community development. There has never been any doubt about your position after the first meeting or two.”

On April 18, 1955, O’Malley writes to renowned architect Eero Saarinen at MIT, “If there is available for public knowledge say photographs or technical articles on your architectural study for the MIT auditorium we would appreciate receiving same. We are now studying the possibility of building a new baseball stadium which would be covered with a 750 ft. diameter translucent fiber glass shell. There is psychological reasons in favor of a translucent material rather than concrete construction to properly set the stage for playing of a game that is traditionally an outdoor one.”

On April 19, 1955, O’Malley writes in an internal memo: “The Brooklyn Dodgers have long been in need of a new modern stadium. Unless a site can be found for such a stadium in Brooklyn the Dodgers franchise will be transferred elsewhere. A plan to be discussed provides for a new stadium in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn plan provides for the elimination of the traffic hazard at Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues. It provides for a new LIRR (Long Island Railroad) depot and will permit the new passenger cars to come into Brooklyn. The Ft. Greene Market Men’s Association can be accommodated at its present site under sanitary and efficient circumstances. The Dodgers will have a new stadium and the franchise will remain in Brooklyn.”

On May 26, 1955, O’Malley sends a letter to eminent architect-inventor R. Buckminster Fuller stating: “For some time we have been considering a new stadium for our Brooklyn Dodgers...My experience in operating a number of typical but antiquated stadia has convinced me that we lose a great deal of money each year because of inclement weather and for some time I have been talking about building a new stadium that, among other things, would have a dome over it of a translucent material...Baseball companies, unfortunately, do not have the resources of the large industrial companies. Price would become an extremely important issue...I believe this would open up a new horizon in baseball...I am not interested in just building another baseball park.”

On August 17, 1955, O’Malley served notice to all that his new stadium intentions were serious, as the 1956 Dodgers would play seven “home” games in Jersey City, New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium. O’Malley repeated his urgent call to find a final solution to aging Ebbets Field. He said, “We plan to play almost all of our ‘home’ games at Ebbets Field in 1956 and 1957 but will have to have a new stadium shortly thereafter. Our present attendance studies show the need for greater parking. The public used to come to Ebbets Field by trolley cars, now they come by automobile. We can only park 700 cars. Our fans require a modern stadium — one with greater comforts, short walks, no posts, absolute protection from inclement weather, convenient rest rooms and a self-selection first come, first served, method of buying tickets. I shudder to think of this future competition if we do not produce something modern for our fans. We will consider other locations only if we are finally unsuccessful in our ambition to build in Brooklyn.”

On September 22, 1955, S.T. Williams, the President of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce issued a press release about the possible improvement of the Ft. Greene Area stating, “Relocation of the ball park and retention of the ball team as an important Brooklyn enterprise is but one possible advantage. Certainly, the downtown parking space would be useful many days of the year. A large, modern stadium need not be used for baseball only, but could be available for cultural and educational activities as well as other sports events…The concentration of transit facilities makes the area an ideal location for apartment housing as well as office buildings and certain industries. Possibly middle-income housing could be included in this area. Such construction would considerably enhance property values and the city’s tax receipts from the surroundings…The President of the baseball club, Mr. Walter O’Malley, has not asked the city to give him a stadium. The area to be studied consists of approximately 500 acres. If the location can be found within this area that is suitable for a new stadium, a constructive result will have been achieved. Mr. O’Malley has said he would buy the site and pay for the stadium structure. It is plain that a private enterprise cannot acquire such at feasible prices. The city seems within its rights and obligations in appropriating $100,000 for study of the site.”

On April 21, 1956, N.Y. Governor Averell Harriman went to Brooklyn to sign a bill (Chapter 951 of the Laws of 1956) to create the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority into law and vowed his support to O’Malley and the Dodgers. According to an interim report of the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority, “This law created the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority for the purpose of constructing and operating a sports center in the Borough of Brooklyn…”

On June 12, 1956, O’Malley writes a note to himself “for stadium file” stating, “Bob Moses sent a memo to (New York) Mayor (Robert) Wagner dated April 23 — In this memo he recommends Flat (Flatbush) & Atlan (Atlantic) site but for a small stadium. A map accompanied the memo. This could be important.”

On October 30, 1956, New York real estate investor Marvin Kratter pays $3 million to the Dodgers to purchase Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and arranges to lease it back for three years (plus two option years through 1961) from Kratter’s assignee, Tillie Feldman.

On April 11, 1957, O’Malley writes an internal memo that addresses his thoughts on a number of issues: “While I was at a conference with (Baseball) Commissioner (Ford C.) Frick at his office Robert Moses called and I suggested that I drop out to his house later in the afternoon. I met Bob at his home in Babylon and we frankly discussed the general political apathy toward the new stadium in Brooklyn. Bob said there was not a chance of the Atlantic & Flatbush site being approved. Marketmen presented a problem and perhaps more important was the Borough President’s determination that the site was wrong. Borough President (John Cashmore) shows some interest in the site on the other side — the one which Clarke & Rapuano recommended. I told Bob that either site would be acceptable to us although we did prefer the LIRR one.”

On May 16, 1957, Abe Stark, president of the New York City Council, proposes Ebbets Field site to be rebuilt to accommodate 50,000 and parking for 5,000 through the acquisition of adjacent land. His proposal was rejected by O’Malley and Moses.

On May 20, 1957, O’Malley writes to Braven Dyer of the Los Angeles Times, “I have not at any time asked anyone to build me a new stadium either in New York or in Los Angeles. This is important in the solution of the entire problem. The money we have made in baseball by the sale of our real estate in Brooklyn, Montreal and Ft. Worth is to be invested right back into baseball in the form of a new stadium. If I am successful in this effort I will have made the greatest financial contribution to baseball that has been made by any ball club in the entire history of the game and that might help a little bit to take the sting out of ever suspected ‘money greedy baseball magnets (sp.).’”

On May 28, 1957, National League owners, meeting in Chicago, voted unanimously to grant the New York Giants and the Dodgers permission to move to San Francisco and Los Angeles, respectively, with the requirement that the two clubs must move together before October 1, 1957. The next day, New York Mayor Wagner requested a meeting with O’Malley and Giants’ owner Horace Stoneham.

On June 26, 1957, in O’Malley’s testimony before the House Antitrust Subcommittee of the Committee of the Judiciary in Washington, D.C. before Chairman Hon. Emanuel Celler, he was asked repeatedly whether the Dodgers were going to play baseball in Los Angeles in 1958. His response: “I do not know the answer for two reasons. One, I do not know what the result of Mayor Wagner’s study in New York City will bring. Two, I do not know whether or not Los Angeles will be ready for major league baseball next spring.”

Responding to charges that O’Malley was playing New York against Los Angeles for the purposes of going to the highest bidder, he explained, “It is a very simple situation, Mr. Chairman. I started out in 1947 trying to get a new ball park for the Brooklyn Dodgers in Brooklyn. We hired an engineer, we conferred with our civic officials, and made very serious studies of various sites.

“It developed that at that time the way could not be found to condemn land to assemble a plot large enough, and, of course, the ball club very properly does not have the legal right to condemn land. But it was hoped that there was enough of a public purpose in the activities surrounding a ball club, particularly if it could be tied in with other things of civic importance such as the relocation of a meat market. The meat market men said that if they were relocated, they could bring the price of meat down 5 cents a pound in Brooklyn. That seemed to be a pretty good civic proposition. There was a traffic intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush which is a very bad one, and some day it is going to be cured.

“That, too, becomes part of a civic purpose in trying to assemble the land at Atlantic and Flatbush. Then there is a question of parking in that area of our community where our department stores are located. Some parking facilities were needed in that area. There was also the observation that the property for the most part was substandard, and had been so designated by Mr. (Robert) Moses as subject to a study for slum clearance.

“We would have relocated our meat market. We would have had parking facilities. We would have cleared up a traffic intersection that was terrible. And all of this would have magically left enough acres of land on which a ball park could be built, at the cost of the owners of the Brooklyn Ball Club, not one penny of which was to be paid by the city of New York. I think that is very important to know.”

On August 26, 1957, the Dodgers issue a statement: “The recent announcement (on August 19) that the Giants are leaving New York City has produced renewed interest in the Dodger problem here and abroad...Locally, the Dodgers are on the record as offering to build their own stadium with their own money at Atlantic & Flatbush Avenues if the land can be made available promptly and at common sense figures. For over a year the Dodgers have had a standing offer to put $5,000,000 in a new stadium to pay $500,000 annual rental plus 5% of gross admissions as a New York City amusement tax. If all efforts fail locally, the Dodgers could buy the necessary land in Los Angeles on which to build their own stadium, which would be on the tax rolls. The same program has been offered to New York City where the Dodgers only need the help of the city in condemning the land.”

On August 28, 1957, Moses writes a letter to Peter Campbell Brown, Corporation Counsel, City of New York, stating in part, “The Atlantic Avenue site is dead for a Sports Center. Time, delays and other factors have killed it. Nor will the improvements other than a Stadium work there without housing...What remains is Flushing Meadow.”

On September 10, 1957, O’Malley writes an internal memorandum regarding the Brooklyn Stadium. “Mr. Mylod’s Brooklyn Sports Center Authority is to come up for consideration before the Board of Estimate on September 18th. Mr. Mylod and I are concerned about a letter that Commissioner Robert Moses wrote to Peter Campbell Brown dated I believe August 28, 1957, in which Commissioner Moses kills the Atlantic & Flatbush Avenue site and persists in making a play for the Flushing Meadow site in Queens. This is a further bit of sabotage which together with the recent quotes of Abe Stark, City Council President, indicates that there is no sincere administration desire to work out a solution here in Brooklyn. Walter F. O’Malley.” The same day, a story breaks on Nelson Rockefeller’s interest in keeping the Dodgers in New York.

On September 18, 1957, O’Malley, New York Mayor Wagner and financier-philanthropist Rockefeller meet at Gracie Mansion to discuss Rockefeller’s proposal to keep the Dodgers in New York. Rockefeller originally planned to purchase for $1.5 million the property that the city would then condemn in downtown Brooklyn. Madigan and Hyland engineering firm had placed the cost of condemning the land at $8 million. Later, Rockefeller’s offer grew to $2 million and then to $3 million. In effect, the $3 million would be a loan to the Dodgers with interest and the acquisition of 12 acres in order to build a stadium.

Rockefeller released a statement on September 20, 1957, in which he said that “The Dodgers have been willing to invest their own funds in constructing a new stadium” and that “The City’s right to condemn the area (necessary land) and to dispose of a part of it to private interests for a stadium was confirmed by Corporation Counsel’s (Peter Campbell Brown) ruling last week.” He also said, “The Atlantic Avenue site desired by the Dodgers is a sub-standard area as the Board of Estimate reaffirmed yesterday.” O’Malley stated, “If we are to stay, we must not only receive the site that is best suited for our purpose, but we must also be given terms that are most reasonable and fair.” In a September 20, 1957 statement by Mayor Wagner, he said “Mr. O’Malley indicated that any proposal involving $3 million for the land priced the Dodgers out.”

On October 7, 1957, the Los Angeles City Council adopts Ordinance #110,204 officially asking the Brooklyn Dodgers to relocate to Los Angeles and bind the city by contract with the Dodgers. The contract obligated O’Malley and the Dodgers to build and privately finance a 50,000-seat stadium; develop a youth recreation center on the land at half a million dollars, plus annual maintenance payments for 20 years of $60,000; plus pay property taxes on land that had not generated any in years (initially $345,000 in 1962). Also, O’Malley and the Dodgers would transfer team-owned Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, then appraised at $2.25 million, to the city. The Los Angeles Angels of the American League used Wrigley Field for home games in 1961.

On October 8, 1957, the Dodgers officially notify the National League of their intention to shift their franchise to Los Angeles by issuing the following statement: “In view of the action of the Los Angeles City Council yesterday and in accordance with the resolution of the National League made October first, the stockholders and directors of the Brooklyn Baseball Club have today met and unanimously agreed that the necessary steps be taken to draft the Los Angeles territory.” Also on this date, O’Malley cited four reasons the Dodgers were unable to remain in Brooklyn after a decade of exploring options with the city to assemble land in order to privately build his own stadium. His four reasons listed in the October 9, 1957 Los Angeles Times: “1 – The desire for a new ball park to replace the aging and outmoded Ebbets Field. 2 — Insufficient parking space adjacent to the ball park. 3 — Dwindling attendance. 4 — A New York City amusement tax of 5% on admissions.”