A night game at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum showing the short left field with the "Monster" screen. The left field screen was only 250 feet away from home plate.

The Miracle Move of the Dodgers From Flatbush to Fantasia

Feature

By Vincent X. Flaherty

Chapter I

While the New York Baseball Writers’ Dinner of 1957 was in full swing at the Astor Hotel on February 3, one of the most important baseball stories of all time was being written on the back of an old envelope.

Walter Francis O’Malley, president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, was the author. He scribbled: “How much will you take for the Los Angeles Angels and Wrigley Field?”

He slid the envelope across the table to Philip K. Wrigley, who not only owned the Chicago Cubs but also the Los Angeles franchise.

Wrigley mulled over the question a minute, borrowed a pen and wrote back:

“Two million for the real estate and ball park and one million for the franchise.”

He spun the envelope across the table to O’Malley, who, without hesitating, wrote: “Deal!” and underlined the word.

That’s all there was to it. No lawyers, no contracts, no formalities, no anything except what was written on the back of the envelope.

As subsequent developments took place in proper order, it turned out to be the biggest deal in modern baseball history – certainly, at least, from a geographical aspect. It set in motion two New York major league franchises crossing the nation in one gargantuan stride of 3,000 miles. It meant Brooklyn was soon to lose the Dodgers after 67 years, and that the 81-year-old New York Giants would be moving with them as an entry, so to speak, in the growing sports gold stampede to California.

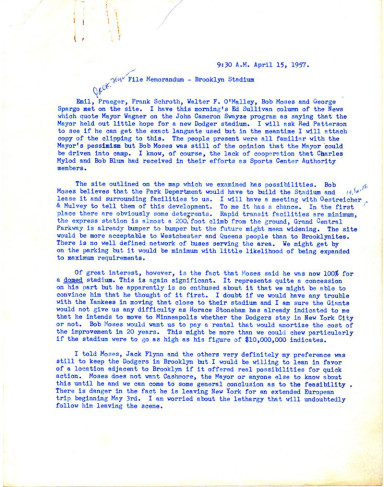

In O’Malley’s internal memo, April 15, 1957, he writes that powerful New York Parks Commissioner Robert Moses has “100% interest for a domed stadium” for the Dodgers, not in Brooklyn but in a location adjacent to Brooklyn and more acceptable to Westchester and Queens people than to Brooklynites…I am sure the Giants would not give us any difficulty as Horace Stoneham has already indicated to me that he intends to move to Minneapolis whether the Dodgers stay in New York City or not.” Stoneham was set to disband his existing Triple-A minor league affiliate in Minneapolis-St. Paul and replace them with the Giants, before O’Malley suggests that he consider San Francisco.

A few days later, O’Malley laid a large bomb on New York from Vero Beach, Fla., where the Dodgers were beginning spring training. He called a press conference and told the assembled writers what had happened. That was February 21, 1957.

Some of the New York writers envisioned it as the beginning of the end for major league baseball in Brooklyn.

Others considered it a strategic move and referred to the Brooklyn baseball boss as “the wily O’Malley,” and added on such descriptive oddments as “shrewd poker player.” They reasoned the valuable Los Angeles territory could be easily unloaded and, after all, O’Malley was still waging a ten-year campaign to have New York clear property for him at Atlantic and Flatbush avenues in Brooklyn. There O’Malley wished to build a modern ball park, at the Dodgers’ expense, and continue baseball in a manner to which Brooklyn had never been accustomed in dowdy Ebbets Field.

The new ball park was to have a bubble dome, and some of the harsher critics hinted O’Malley had come up with a bubble-brained idea. Eventually, O’Malley’s dream was to burst like a bubble. Having already sold Ebbets Field, he had to plan for the future, but O’Malley’s every move was balked. All kinds of possible sites for the new Brooklyn park were suggested – the most convenient of which was only slightly nearer than Perth Amboy, N.J.

That was just about the size of it. The Dodgers couldn’t make a deal in New York, where the pastures can be as green as an apprentice plumber. So O’Malley took a fond look on the yonder side of the Rockies. It looked awfully green – LONG green.

Meanwhile, O’Malley and Horace Stoneham, president of the New York Giants, had struck up an unusual fondness for each other. They had had frequent discussions. Stoneham was well-versed in the California baseball potential. He had been briefed by such transplanted easterners as Leo Durocher and this writer, who, having become hardy pioneers, sang the praises of the Pacific shore.

O’Malley had gotten an earful also. Charley Dressen, his manager before the big move, had chattered away about Los Angeles incessantly until O’Malley threatened to wash out his mouth with a cake of soap for even insinuating the Dodgers could be extracted from Brooklyn.

O’Malley, too, had been subjected to a long-winded correspondence course dealing with such intriguing Los Angeles facts as the record football attendances, collegiate as well as professional; and financial figures of America’s two richest tracks, Santa Anita and Hollywood Park; the consistently top boxing take, despite second-rate attractions, and a sprig of fascinating figures showing that 100,000 people packed the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day while practically down the street, on the very same day, another 85,000 sports fans jammed Santa Anita for the races.

Following O’Malley’s announcement on February 21, the full details of the Wrigley-O’Malley transaction became public. In addition to the outlay, O’Malley and Wrigley swapped minor league holdings, with Wrigley taking Fort Worth while O’Malley took complete charge of Los Angeles.

If this wasn’t enough to stir uneasiness among New York baseball fans, Stoneham announced the very next day (February 22, 1957) the Giants would leave New York, too, if the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles.

This was the first intimation that Horace had entertained the slightest notion of moving his Giants. The Stoneham statement, however, was more believable than O’Malley’s possible move. The Dodgers had done handsomely at the box office in Brooklyn, despite limited seating and practically no parking facilities.

Conversely, the Giants were a hardship case. They had beaten Cleveland four straight in the World’s Series and had lost money – the only instance in modern baseball where a championship team went into the red. Winning a National League pennant and the World’s Series created an additional financial hazard for the Giants. As is the custom with championship players, all of them demanded or expected raises for the 1955 season. Stoneham handled the critical salary situation as best he could. But the Giants fell to third place in 1955 and dropped to sixth place in 1956 and ’57 – and attendances at the Polo Grounds dropped commensurately.

Thus, Stoneham had to do something drastic – and the move to San Francisco was the least risky solution of his mounting problems.

Stoneham wasted no time in purchasing territorial rights to San Francisco from the Boston Red Sox, who owned the minor league franchise. In fact, once he started moving, he moved faster than O’Malley. Weeks before O’Malley was to make a definite statement concerning the Dodgers’ future, Stoneham announced the Giants were through with New York and would be playing in San Francisco as of April, 1958.

“Whether or not the Dodgers move to Los Angeles,” said Stoneham, “the Giants are definitely going – even if we have to go it alone.”

That didn’t mean O’Malley hadn’t made up his mind. He was obligated to delay his announcement because New York had renewed its efforts to find the Dodgers a new ball park location. Much was made of a potential site in Flushing Meadow. Governor Averill Harriman and Mayor Robert Wagner joined the campaign to “save the Dodgers.”

O’Malley knew too many political ramifications were involved. He knew his New York cause was utterly hopeless, but in deference to the governor, mayor and other loyal politicians, he decided to delay definite action until the last possible instant. When it was obvious nothing was going to be done, O’Malley waited until after the 1957 World’s Series to announce his transcontinental switch.

Would he have kept the Dodgers in Brooklyn if a practical park site had been made available?

He now says: “Beyond any question. I would have been obligated to stay. I would have liked to have stayed.”

Chapter II

Crowds? You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet!

That doesn’t mean he regrets his ultimate decision. Glittering box office figures show the Dodgers have come into the richest major league baseball territory in the nation – a city with a booming population, large industries and wonderful weather.

Los Angeles offers something few major cities can provide a big league team. It doesn’t rain in Los Angeles throughout the baseball season – therefore no costly postponements, no fans staying away because “It looks like rain” or because it is too cold. In other cities, an entire series can be rained out, causing a dead loss at the box office that cannot be recouped. O’Malley was well aware of this important little item before he purchased Wrigley Field and the Coast league franchise.

The first pitch of Major League Baseball in Los Angeles is thrown by right-hander Carl Erskine on April 18, 1958 at the LA Memorial Coliseum.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Los Angeles has more than lived up to O’Malley’s expectations as a baseball community. Without resorting to lily-gilding, he says, “This is the greatest!” In 1959, the Dodgers established all kinds of attendance records. Counting regular games, the All-Star Game, a Yankee-Dodger exhibition, the National League playoff and three World’s Series games, the Dodgers’ home attendance soared to 3,110,983. The Yankee-Dodger exhibition, honoring Roy Campanella, drew more than 93,000 paid admissions. Police estimate 20,000 fans were turned away from the Coliseum gates. This was the largest baseball throng of all time.

In three World’s Series games against the White Sox, new attendance records were established every day. The first game drew 92,394 paid admissions. The second game drew 92,650. The third game drew 92,706 – and the only reason the crowds weren’t even larger was due to fire regulations.

In view of those tremendous turnouts it might seem absurd, therefore, to say the Dodgers have yet to realize their full box-office potential. The Coliseum is the greatest stadium in America – but not for baseball.

During his first two seasons in the Coliseum, O’Malley cut day baseball down to a minimum. During the season of 1960, the Dodgers will play more night games at home than any major league team, simply because of the hot summer afternoons.

The atmosphere outside of the Coliseum usually is wonderful and the breezes salubrious. But the playing field and choice seats at the Coliseum are two stories below street level. Breezes are cut off by the towering stands more than 100 feet overhead. So the sun bakes the Coliseum concrete and the hot, heavy air hangs at the stadium bottom. Playing field temperatures have reached 120 degrees.

Thus, forced to play almost all of their games at night, the Dodgers have yet to avail themselves of the patronage of America’s largest population of wealthy or semi-wealthy retired people, as well as untold thousands of night-shift factory workers.

Because of the daytime discomforts of the Coliseum, the Dodgers are compelled to pass up patronage of thousands of people who cannot stay up until midnight for night games. Twilight baseball was considered as a solution, but the terrific Los Angeles traffic at that time of the day ruled against it. So the real Los Angeles test won’t come until the Dodgers have their $16,000,000 stadium erected in Chavez Ravine, which is located just a Duke Snider clout from City Hall, in the very hub of the freeways. It will be within 30-minutes driving distance of six million people.

Presentation made by Mrs. Rosalind Wyman, Los Angeles City Councilmember (at microphone in center of photo) on May 7, 1959, the tribute game for Roy Campanella. The game drew a then record crowd for a baseball game with 93,103 in attendance.

O’Malley says he started thinking of Los Angeles as the future Dodger home five years before he actually made the move. Branch Rickey, when general manager of the Dodgers, often mentioned the baseball possibilities in Los Angeles. But Branch never mentioned it in terms of moving the Dodgers. Rickey was a strong advocate of building the Pacific Coast League into a third major league.

O’Malley also listened to the enthusiastic talk of Leo Durocher and Charley Dressen when they were Dodger managers. Being of the Beverly Hills swimming pool set, they were Los Angeles rooters. However, Dressen was the first to make the suggestion that O’Malley move the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

The Dodger president now allows that Dressen “might have planted a seed.” O’Malley needed quite a bit of persuasion, for he had his heart set on the fulfillment of his Brooklyn dream. He did not favor the shifting of franchises.

In fact, he now reveals he was vigorously opposed to the Boston Braves moving to Milwaukee. He had plenty of National League owners sharing his thinking, although he is the first to admit now that he was wrong. Lou Perini, president of the Braves, and his assistants put on quite a campaign among the National League owners before the transfer was put up to a vote.

Meeting on March 18, 1953, the N.L. owners split, 4 to 4, in their first ballot on the proposal to permit the transfer of the Braves. Perini needed unanimous consent. On the second ballot, there were six votes in favor of the move, but two still were against it. The holdouts were O’Malley and Rickey, then of Pittsburgh. Finally Rickey and O’Malley swung over and gave Perini a unanimous 8 to 0 vote. The first big league franchise in a half century was shifted, and the Braves took Milwaukee by storm in 1953.

The transfer of the Braves had a profound effect on O’Malley’s thinking. The Braves immediately started creating attendance records. They turned a huge profit at the close of their first season. Although Milwaukee County had lured the Braves with a flat rental of $25,000, a grateful Perini announced he was voluntarily upping the rental to $250,000. The Braves immediately started pumping their fat profits back into the ball club. They consistently outbid all other teams in signing young talent.

By 1957, when the Braves displaced the Dodgers as National League champions, O’Malley took a close look at things. He realized the chances were the Brooklyn box-office dollar would never be as large as Milwaukee’s. In his re-appraisal, he decided baseball men had been dealing in pure fallacy in saying, “You can’t buy a championship team.”

Volumes had been written about the millions Tom Yawkey had spent in trying to build his Boston Red Sox into pennant winners. But mostly, Yawkey had sunk a fortune into fading stars with the exception of Joe Cronin, still a great player when Yawkey bought him from Washington for the record price of $250,000.

Instead of paying out huge sums for fading stars, the Braves went to the bottom of the ladder and paid fancy bonuses to mere juveniles. Perini’s bonus babies started coming through. O’Malley now says: “I finally decided the only way the Dodgers could beat the Braves would be to make more money than the Braves.”

Since moving to Los Angeles, the Dodgers have become the heaviest spending team in all of baseball and have corralled more young talent than any other team during the past two years. That bonus talent could be paying off this year with the likes of Frank Howard and Don Demeter, two towering specimens of young manhood who, some say, are headed for greatness.

It might be said the Dodgers are the “spendingest” ball club in history on a two-year basis. Aside from paying fat bonuses to youngsters, the transcontinental broad jump from Brooklyn to Los Angeles has been an enormously costly adventure.

But if O’Malley thought he had troubles with politicians in New York, his experience in Los Angeles was a new one in monumental headaches.

The “wily O’Malley,” the “shrewd,” the “smart poker player” O’Malley, as New York sports writers have described him, after the move had every reason to believe he would be welcomed as a conquering hero when he came to Los Angeles.

The Dodger boss was promised everything by sincere members of the City Council and County Board of Supervisors before he moved the Dodgers.

Chapter III

Baseball’s Biggest Spenders

In February, 1957, representatives of the two governing groups flew to Vero Beach, Fla., to clinch the Dodgers, with Mayor Norris Poulson leading the way. The Mayor was sincere, too, and still is. But unreckoned with was a group of obstructionists within the city and county governments, who have thrown roadblocks against the Dodgers at every turn.

At the Vero Beach meeting, the Dodgers were to get reasonable rental in the Coliseum. They were to get 365 undeveloped acres in Chavez Ravine, an unkempt and disreputable piece of real estate. The Dodgers, in exchange, were to give the city Wrigley Field and the real estate it occupies. The Dodgers were to pay for grading the property. They were to build, at their own expense, a recreational area for Los Angeles kids. They were to build a 16-million dollar stadium at their own expense. The city and county was to do such things as install access roads.

From Left to right – Kenneth Hahn, Los Angeles County Supervisor, Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson, Dodger center fielder Duke Snider and Dodger President Walter O’Malley at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida on March 6, 1957. Hahn, Poulson and other officials from Los Angeles visited Dodgertown to discuss O’Malley’s future plans. Note the Los Angeles banner in the background, though O’Malley had not decided on the team’s future plans.

All of these promises were well-intended by the politicians who met with O’Malley at Vero Beach. But the fact remains, O’Malley really had nothing sewed up when the Dodgers made the big move.

Baseball-wise, the Dodgers’ position was identical with that of the Braves when they moved to Milwaukee. The Braves owned the Milwaukee American Association franchise and therefore owned the territory. They paid the American Association little more than $50,000 in damages. A similar situation existed when the St. Louis Browns were moved to Baltimore.

Certainly O’Malley had every reason to believe his invasion of Los Angeles would work out automatically – with Milwaukee and Baltimore having set a baseball precedent. So when the Coast league called a meeting to discuss damages, O’Malley didn’t feel his presence was necessary. He dispatched others to represent him.

Whereas Milwaukee, Baltimore and Kansas City came cheaply, the Dodgers and Giants were socked with large damages. Jointly, they paid the Coast league $900,000—or $450,000 apiece.

When they learned what had happened, both O’Malley and Horace Stoneham were stunned. But where Stoneham otherwise has come through unscratched, O’Malley was to encounter mounting troubles.

A group which sought to claim Chavez Ravine for a World’s Fair took up referendum petitions designed to keep the Dodgers out of the area. Thousands who signed didn’t stop to think the Dodgers already had agreed to move to Los Angeles in 1958.

Armed with the necessary signatures, the Dodger-Chavez proposition was placed on the ballot, and the Dodgers narrowly won a decision. All through these wasted months when O’Malley wanted to start on his big, beautiful Taj Mahal, building prices were increasing.

Plans for the Dodgers’ new stadium call for a regular opera house of a ball park with lavish restaurants, a private club on the order of the elaborate Turf Clubs at Santa Anita and Hollywood Park, a seating capacity of 56,000 and a parking area for 30,000 automobiles.

It will be a sharp contrast in luxury when compared to the lumber seats of the Coliseum and the lesser concessions fare of hot dogs and cold drinks.

Minority political opposition succeeded in throwing the Dodgers’ stadium plans in reverse all the way. O’Malley first expected to have his stadium ready for the 1959 season – then was forced to count on 1960 for the grand opening. Now O’Malley will count his lucky stars if the new park is ready by mid-1961.

The latest kick in the Dodgers’ cash box was levelled by property owners in Chavez Ravine. Although the city condemned the property, the property owners held out for more money than the court evaluated the value of the array of shanties and one grubby grocery store. The Dodgers were stuck for another half-million dollars to purchase 12 parcels of land that the city had neglected to acquire and still another $1,800,000 for extra grading on the property. What with Coliseum costs, purchasing property and legal involvements, the Dodgers will have sunk close to $6,000,000 into Los Angeles without a stadium in sight.

In order to play baseball in the Coliseum, they paid all expenses for alterations and physical improvements in the big stadium. It cost them $35,000 to erect the now famous Chinese screen in left and left-center fields, build a fancy baseball press box, install a backstop, put up protective screens for the fans and cover the reserved seat areas with foam rubber cushioning. Engineering for Chavez Ravine has cost $600,000, excess grading in the Ravine another million.

Now the Dodgers have to come up with eight million for the first phase of the stadium. The Dodgers are obligated, by agreement, to spend $1,700,000 over the next 20 years for the 40-acre youth recreation center.

Meanwhile, O’Malley isn’t grumbling – mumbling to himself, maybe, but he isn’t grumbling, at least outwardly.

The man has strived to establish himself in Los Angeles as a solid new citizen and a good neighbor. Donating the 40-acre recreational center in Chavez Ravine was his idea – not the city’s or county’s. He considered it a good-will measure for an incoming easterner, although the applause for the costly gesture didn’t build up enough to become a faint echo.

Chapter IV

New York’s Fight to Keep Dodgers

Despite roadblocks, hiked prices and the rental for the Coliseum, the Dodgers figure to do handsomely once their new stadium comes into being. Meanwhile, that 3,110,983 attendance in 1959 soothed a multitude of wounds. Certainly the Dodger players aren’t complaining. After walloping the White Sox, they dragged off the all-time record World’s Series melon, with 29 players each getting $11,231. The White Sox could not complain much, either—even if they lost. They got the all-time record loser’s share of $7,275—all because they played three Series games in that big concrete crater in Los Angeles.

The “1960 Baseball Register” published by The Sporting News featured an article by syndicated columnist Vincent X. Flaherty detailing the Dodgers’ journey to Los Angeles. For years, Flaherty wrote letters to Walter O’Malley heralding Los Angeles as the best site for the Dodgers to relocate.

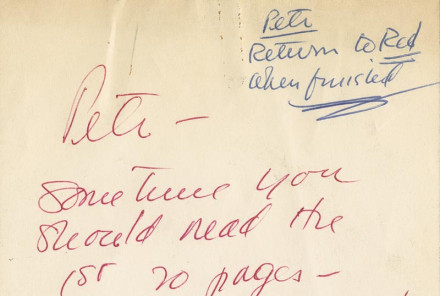

A hand-written note from Dodger President Walter O’Malley to his son, Peter encouraging him to read the article by Vincent X. Flaherty in the 1960 Baseball Register published by The Sporting News.

Going back, it can be recalled that August and September, 1957, was a hectic period for New York sports fans – not to mention New York newspapers which made the Dodgers and Giants front-page stuff.

Down to the wire, it was said O’Malley was bluffing. The Dodger boss became the villain in the Gotham playlet. Little was heard from Horace Stoneham, president of the Giants, since his February 22 statement that, if the Dodgers moved to the Coast, the Giants might move, too.

But on August 19, Stoneham shook things up when he announced the Giants definitely were moving to San Francisco—regardless of whether the Dodgers moved or not.

San Francisco had promised to build the Giants a fine stadium—which it has now done. It would be rented to the Giants on a 35-year lease. The rental was set by the city at five per cent of receipts after taxes, with a minimum guarantee of $125,000 annually by the Giants. Obviously, San Francisco considered major league baseball a resounding civic asset.

Three days after Stoneham dropped his block-buster, the New York Herald Tribune, curiously enough, blasted a story with the following head: “Dodgers Willing to Remain If City Condemns Land.” In the interest of accuracy, the head should have added: “…and Sells It to Brooklyn Club.”

Walter O’Malley, Robert Wagner, Horace Stoneham and John Cashmore (L-R) following June 4, 1957 meeting at Mayor Wagner’s office.

New York’s Mayor Wagner, Governor Harriman and politically aspiring Nelson Rockefeller now were working furiously to salvage at least the Dodgers. New York maintained a running patter of political quotes as to what it was or wasn’t going to do for the Dodgers. It went on for weeks. It moved over the Milwaukee-Yankees World’s Series in the news.

October 8, 1957, was an open date for traveling in the New York-Milwaukee Series. Warren Giles, president of the National League, picked the off-day as the time to announce the transfer of the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

Pre-game news for the sixth Series game in New York was reduced to a bare nothing on October 9 when the Braves and Yanks returned to Yankee Stadium. The New York Times played the announcement on the front page, and the entire first page of the sports section was monopolized with news of the transfer.

Indeed, the only mention of the sixth game on the first sports page amounted to a tiny corner box, bearing the head: “Clear Skies Predicted For Sixth Series Game” The rest of the page was devoted mainly to a photographic spread showing deserted Ebbets Field with an insert of Charles H. Ebbets, shots of Dazzy Vance, Uncle Wilbert Robinson, Zack Wheat, Casey Stengel and other former Dodgers, front office to batboy.

The Dodgers weren’t in any Series at all, but the Times was loaded with nostalgic stories about former Dodger managers and stars, year-by-year Dodger records and pennants won. And there was an off-beat story quoting the New York Transit Authority to the effect subways would lose $300,000 annually because the Dodgers and Giants had vamoosed. All other New York newspapers were loaded the same way, and any baseball fan would have had to put on a thorough search to find out Bob Turley was starting for the Yankees against Bob Buhl for Milwaukee.

So, what’s going on in the golden land of Los Angeles at this point? Despite setbacks, despite costs, Walter O’Malley has every reason to believe his Dodgers will become the new dynasty, the new invincibles of baseball.

There is a man slightly less than 500 miles to the north of Los Angeles who has ideas of his own—Horace Stoneham. He plans to bring the Giants to a point where they never had it so good, even during the days of John McGraw. Stoneham has the city. He has the metropolitan population and the fans, once impoverished when such home-growns, like Harry Hooper, Ping Bodie, Tony Lazzeri, Lefty O’Doul, Lefty Gomez, Joe Cronin, the DiMaggio boys and so many others had to go east to make a name. Stoneham also has a beautiful new park at his disposal at reasonable rental for 35 years. Here on in, peg them as the “wealthy Giants.”

Chapter V

The Race to Capture California

Between O’Malley and Stoneham, they performed a feat of Herculean acrobatics in hurling baseball’s greatest rivalry 3,000 miles. The “Subway Series” is no more. Chances are the championships of the National League will be settled in California more years than not, and that the “jet,” or “rocket series” has already replaced the subway.

If you wish irony, the American League had first crack at claiming California—a running shot at it for four straight years, but California was “too far.” The American League, once the most powerful major loop, may be destined to inherit the unhappy role the National League had to bear for too many years –with a lopsided record in World’s Series and All-Star play.

That’s the thinking in three National League cities—Milwaukee, Los Angeles and San Francisco. It is a bit of thinking substantially supported by current records.

The large crowd of 92,394 fans attend Game 3 of the 1959 World Series on October 4 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. It is the first World Series game played in Los Angeles and set a record for the attendance, only to be broken the next day (92,650 fans). The day after that, another record which still stands, 92,706 fans. The Dodgers beat the Chicago White Sox in six games to win the first World Series championship in Los Angeles and second in Dodger history.

And just think! A few years ago the transfer of the Giants and Dodgers from New York would be a heresy tantamount to tearing down Brooklyn Bridge, which opened the year (1883) that George Taylor, city editor of James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald, founded Brooklyn’s first professional baseball team. George Taylor had his professionals play in a ramshackle field called Washington Park, so named because George Washington’s Continental Army fought the Battle of Long Island on that site. With tired wooden stands, it held 1,200 people.

In contradistinction, the Dodgers and Giants will be playing baseball in America’s two most modern stadiums. Maybe a hundred years beyond George Taylor’s thinking, maybe not.

There are a number of people responsible for the breaking up of the once dormant baseball map. They are all Californians, either through nativity or adoption.

Foremost is former Rep. Patrick J. Hillings. Los Angeles-born, he served on the House of Representatives Sub-Committee on Monopolies. He is the one man really responsible for changing the major league baseball face of America.

Chairman of the committee was Rep. Emanuel Celler, of Brooklyn. The committee was to investigate baseball’s reserve clause, wherein ball clubs bind a player by contract.

Hillings turned the hearings upside down, converting them into an investigation of baseball’s geographical aspects. He wanted to know why cities west of St. Louis should not be entitled to representation on the major league map.

Hillings got one major league owner after another on the stand in the committee room. Finally, Phil Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs and the Los Angeles Angels, made his appearance.

“Why shouldn’t California have major league baseball?” asked Hillings.

As recorded in the Congressional Record, October 17, 1951, Wrigley said:

“I am sure Los Angeles and San Francisco could support major league baseball, and I am sympathetic with their aspirations. Some day I would like to see them in the big league through absorption into the present majors or in a new league if it didn’t wreck the Pacific Coast League.”

Chapter VI

A Lonely Politician’s Valiant Struggle

Wrigley was the first major league owner cognizant of California baseball values. He was sympathetic, very well aware of the potential.

The Congressional Record of October 17, 1951, also goes on:

“Question, Mr. Hillings: ‘I have just another question. Yesterday, Mr. Wrigley, the chairman (Emanuel Celler) read a letter from Mr. Vincent X. Flaherty, of the Los Angeles Examiner, which was placed in the Record, in which Mr. Flaherty said he thought you would be willing to sell the Los Angeles franchise out on the West Coast in order to facilitate the development of major league baseball. We asked Mr. Leslie O’Connor, president of the Coast league, who testified yesterday, about that point raised by Mr. Flaherty. Mr. O’Connor thought you would probably rather desire to hold onto the Los Angeles franchise than maybe the Chicago Cubs’ franchise when it came to making a choice…’”

Rep. Hillings followed up with the question:

“What then would be your further comment on the statement of Mr. Flaherty?”

According to the Congressional Record, Wrigley replied: “I have always said I would never stand in the way—in fact, because any major league team can go in (into Los Angeles), and if they get permission of their own league, take the territory…”

Hillings hammered away, through the then Commissioner A. B. (Happy) Chandler, down through the owners. Instead of investigating the reserve clause, Congress was now investigating geographical monopoly in the major leagues.

Chairman Celler, a Brooklyn fan, was unknowingly letting his Dodgers get away. He had good reason to feel secure about the Dodgers. Of all the major league teams that might be moved—certainly the Dodgers weren’t among them, at that time.

(L-R) Los Angeles City Councilmember Rosalind Wyman; Walter O’Malley; New York Yankee Manager Casey Stengel; Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson. Standing – Dodger Manager Walter Alston and unidentified. Alston, Wyman, O’Malley, Stengel, Mayor Poulson at the dais of the “Welcome to LA Dodger luncheon” on October 28, 1957.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

In Los Angeles, County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn was the first to demand major league baseball for Los Angeles. He was ridiculed on all sides, mostly by the Los Angeles sports press which, for various reasons, was in league with the Coast league. That didn’t include the Los Angeles Examiner.

Hahn was the political loner in Los Angeles until a pretty young lady named Rosalind Weiner (later Mrs. Gene Wyman) was elected to the hitherto 15-man City Council. (Rosalind made it 14 men and one brunette newcomer.) While Hahn was storming for major league baseball among the County Supervisors, Rosalind was carrying on the same campaign in the City Council.

Both Hahn and Rosalind suffered abuse from many sources—not counting the sports conscious fans of Los Angeles who were enthralled over the prospects of major league baseball.

Finally, Mayor Norris Poulson came into the fold. When the St. Louis Browns were being transferred to Baltimore—instead of Los Angeles, where they were supposedly headed—Poulson addressed the American League meeting at the Commodore Hotel in New York and said:

“Gentlemen—we are in no hurry for major league baseball in Los Angeles. Maybe 20 years from now. I don’t want to deprive Baltimore of the Browns. Wait until our war babies grow up in Los Angeles—that will be plenty of time. You will come running to us.”

Unfortunately, nobody came running to Los Angeles.

The move had to be pushed and hammered by Pat Hillings, the man who broke up the baseball map and made it possible for all moves of franchises…Kenneth Hahn, who moved in where Los Angeles (Angels?) feared to tread…Rosalind Wyman, who came into political prominence from nowhere but immediately adopted the major league baseball crusade as her foremost fight.

Hillings (mostly), Hahn, Mrs. Wyman and Poulson—these were the people who got major league baseball in Los Angeles and thus San Francisco and deserve the lion’s share of credit.

Chapter VII

Impressive Past – Fantastic Future

Aside from briefing every major league owner about the California potentials, this newspaperman wrote letters to, or talked to, columnists in many major league cities. As a result of his pioneering, columns or items that were to be far-reaching were written in New York by the late Grantland Rice, the late Bill Corum, Walter Winchell, Bob Considine, Jimmy Cannon, Red Smith, Arthur Daley, Frank Graham and Dan Parker. In Chicago, it was Warren Brown, John Carmichael, Arch Ward, Gene Kessler and Irv Kupcinet.

In Detroit, there was the late Harry Salsinger; in Boston, Austen Lake and the late Dave Egan. In Washington, the important scene, Shirley Povich, Bob Addie, Morris Siegel and Frances Stann wrote about it.

THE SPORTING NEWS backed it through publisher J. G. Taylor Spink. At the Commodore Hotel, when the St. Louis Browns were being switched from his home town to Baltimore (snatched the last instant from L.A.), Spink said:

“Don’t worry. Major league baseball will be in California.”

So it is, true to Spink’s words, and so it shall be—larger than reality itself, and fantastically profitable and awfully big. Baseball has grown modern.

The Dodgers have now won ten pennants and two world’s championships. The Giants have won 15 pennants and five world’s championships. From here on it, it looks better, much better. The Dodgers and Giants now share baseball’s greatest talent farm—California.

Los Angeles Examiner columnist Vincent X. Flaherty pins a flower on Dodger Manager Walter Alston at a “Welcome Dodgers” luncheon prior to the 1958 season opener. Flaherty initially corresponded with Walter O’Malley in 1953, expressing the interest of Los Angeles officials to bring Major League Baseball to the West Coast.

AP Photo

Time has spanned quite a distance since the first Giants and the first Dodgers. George Taylor, a realistic dreamer, founded the Dodgers. But even he would be astonished over what’s happened to them since…straight along with the likes of Steve and Ed McKeever, Charlie Ebbets, Wilbert Robinson, Ned Hanlon, Nap Rucker, “Wee Willie” Keeler, Bill Dahlen, Zack Wheat, Dazzy Vance, Max Carey, Otto Miller and to the moderns of Babe Herman, Van Lingle Mungo, Dixie Walker and Jackie Robinson.

Zachariah Davis (Zack) Wheat, one of the greatest of all Dodger players, threw out the first ball to open the Dodger-White Sox World’s Series in the Los Angeles Coliseum. Zack had come from his native state of Missouri, where he had been born 71 years before.

Zack, acting like a 39-year-old, went to the pticher’s box and whipped one over to Johnny Roseboro, the Dodger catcher. He drew an enormous ovation.

The wonderful Dodger outfielder of the 1920s and Hall of Famer, who once had a batting average of .375, left the pitcher’s box and jogged beyond the backstop.

There a number of sports writers were waiting.

Zack surveyed the immense throng of 92,394 people and said:

“Tell you something! Never saw anything like this in Brooklyn.”