Wyman’s Historic Efforts Bring Dodgers to Los Angeles

By Brent Shyer

It took a 22-year-old with leadership, courage and vision to encourage the Brooklyn Dodgers to come to Los Angeles.

Convinced that it was the right course of action for the City of Los Angeles to take, the University of Southern California graduate was compelled to push for the Dodgers, even when it seemed only a remote possibility.

Today, it is more commonplace to have cities interested in luring a professional sports team to relocate. But, in the 1950s, Major League Baseball did not even field a team west of Kansas City. When the Boston Braves relocated to Milwaukee for the 1953 season, it snapped a 50-year period of no movement by teams.

The campaign staged to attract a team -- and not just any team, mind you, but the 1955 World Champion Dodgers — said all one needs to know about the ambition of this elected official.

“Right now, I’m deep in plans to bring major league baseball to Los Angeles. Everybody wants it and we should have it. Baseball is a big business. We have the climate and Los Angeles is a great sports town. We need big league baseball. It would be great for the kids, too. They are great worshippers of top sports figures and sports-minded kids are never delinquent.” Anne Norman, Los Angeles Times, Roz Wyman Has Simple Method to Win Votes; She Rings District Doorbells and Gets to People, April 7, 1957

This quote was delivered in April of 1957, not by the Mayor of Los Angeles, but by a woman.

That’s right, the youngest City Councilperson in the history of Los Angeles, Rosalind Wyman, made that statement, filled with hope that she and a cadre of local officials could woo Walter O’Malley and the Dodgers westward, providing he paid to build the stadium. It was one of the biggest gambles in the City’s history, but one, once achieved, that proved to be the mother lode of risk-taking success.

Wyman was right in the middle of the achievement and turmoil. Los Angeles voters, in fact, had rejected a ballot measure to fund a $4.5 million bond to build a baseball stadium on May 31, 1955, meaning any team relocating there would have to privately finance a ballpark.

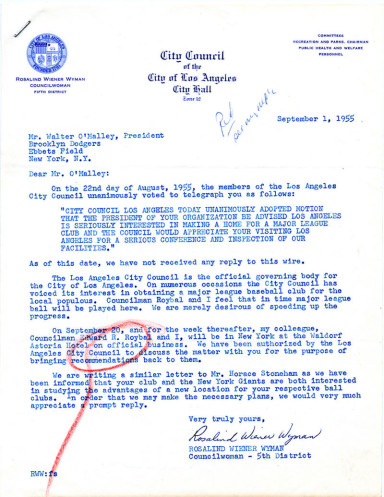

On September 1, 1955, Roz Wyman, Los Angeles City Councilwoman, sends a letter to Dodger President Walter O’Malley asking if she and Ed Roybal, another member of the Council, could meet with him in New York. Wyman wanted to discuss the possibility of bringing the Dodgers to Los Angeles. O’Malley, who was focused on trying to find a way to build a dome stadium in Brooklyn, wrote her and declined her offer.

Initially, she wrote a letter to O’Malley on September 1, 1955, asking for a meeting with him to gauge his interest in relocating. One year prior to that, the City Clerk, per approval by the Los Angeles City Council, sent a letter to major league baseball team owners asking them to consider L.A. as a site for their team. Officials, who were convinced that it was only a matter of time before one of them accepted the offer, were making preparations to review possible locations for a ballpark. Los Angeles played home to two Pacific Coast League teams, the Los Angeles Angels who played at Wrigley Field at 42nd and Avalon and the Hollywood Stars, who played at Gilmore Field on Beverly Boulevard. But, that was minor league baseball, not the majors.

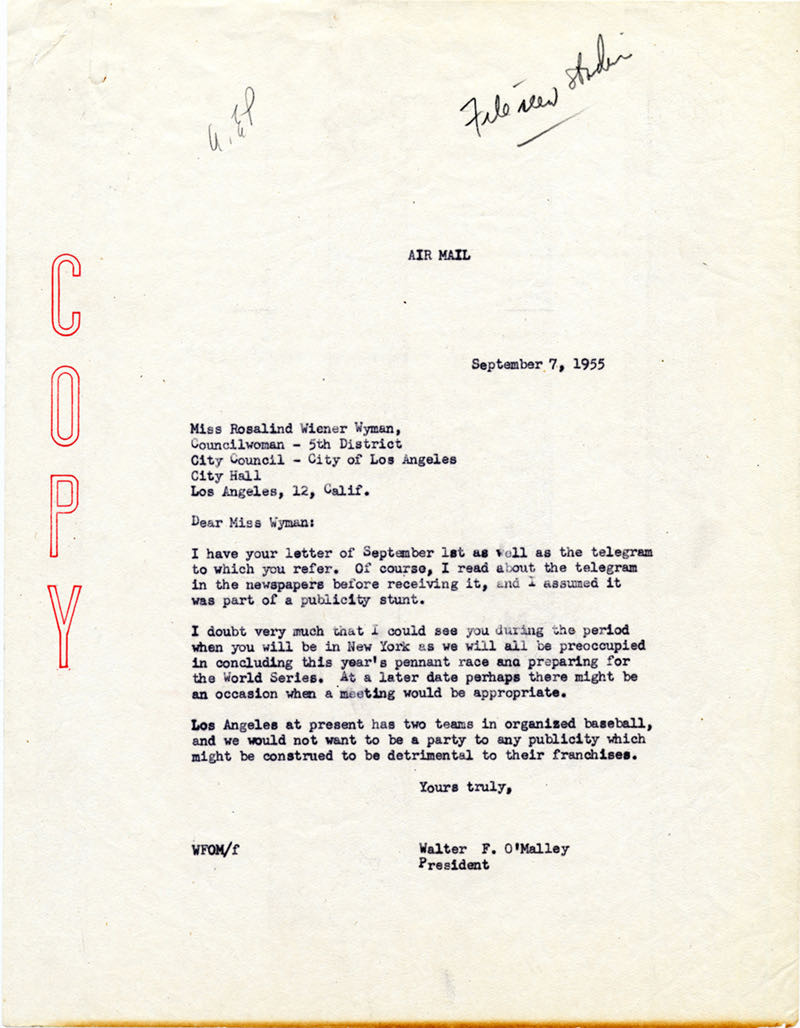

O’Malley responded to Wyman on September 7, 1955 that “I doubt very much that I could see you during the period when you will be in New York as we will all be preoccupied in concluding this year’s pennant race and preparing for the World Series...Los Angeles at present has two teams in organized baseball and we would not want to be a party to any publicity which might be construed to be detrimental to their franchises.” Letter from Walter O’Malley to Roz Wyman, Councilwoman — Fifth District, Los Angeles, September 7, 1955

Dodger President Walter O’Malley writes a September 7, 1955 letter to Los Angeles City Councilwoman Roz Wyman declining the invitation to meet with her and Councilman Ed Roybal in New York. At the time, O’Malley’s focus was on trying to build a dome stadium in Brooklyn, plus the busy preparations for the Dodgers in postseason play.

His focus was clearly on working out a solution to aging Ebbets Field in Brooklyn by building a new domed stadium, the first of its kind in baseball, at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues. He had begun the process of addressing Ebbets Field as early as 1946, four years prior to becoming President of the Dodgers, and continued his painstaking work over the next decade with elected and appointed officials to bring about a resolution at the site he preferred in Brooklyn.

But, the Los Angeles contingent of Wyman, Mayor Norris Poulson and legendary L.A. County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn were persuaded that a major league baseball team was necessary in order for the city to finally gain the status it was looking for in the 1950s — big league in every way.

Playing with the “big boys” in an era in which women were beginning to advance into politics, never stopped pioneer Wyman from realizing her dreams and the early shaping of Los Angeles as one of the premier destinations and places to live.

“I think the government needs women,” Anne Norman, Los Angeles Times, Roz Wyman Has Simple Method to Win Votes; She Rings District Doorbells and Gets to People, April 7, 1957 she said in 1957.

A proud day indeed for Los Angeles, as its Mayor Norris Poulson and City Council members celebrate the Dodgers acceptance of the city’s contract offer on October 8, 1957. First row behind Poulson (left to right) are council members Ransom Callicott, Roz Wyman, Gordon Hahn and Charles Navarro, while behind them (left to right) are John Gibson, L.E Timberlake, James Corman and Everett Burkhalter.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

During the summer of 1957, Mayor Poulson dispatched Harold “Chad” McClellan to New York as the official negotiator on behalf of the City and County of Los Angeles to meet with O’Malley and the Dodgers. As negotiations progressed, it was crystal clear that O’Malley wanted to privately-finance, design, build and maintain Dodger Stadium. He was looking for a site to build his dream stadium.

McClellan said in the Los Angeles Times on September 17, 1957, “If the Dodgers accept the plan and build the stadium this will be the biggest bargain any city has had in getting major league baseball in 20 years.” Paul Zimmerman, Los Angeles Times, Deal For Dodgers Gets L.A. Council Approval, September 17, 1957

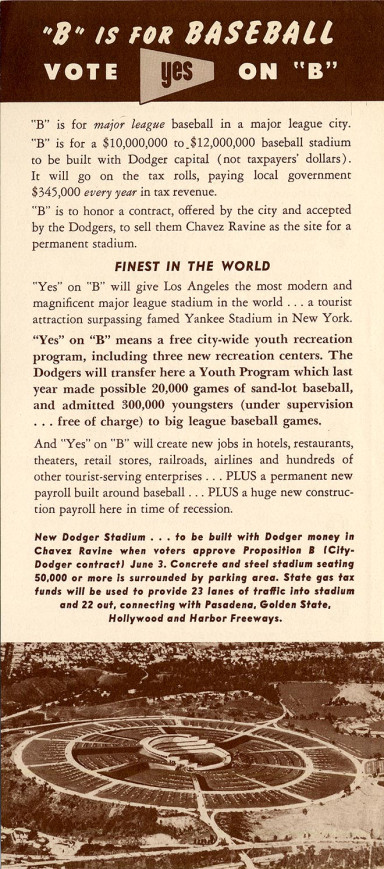

That was because public funding was necessary for ballparks built in Milwaukee (1953), Kansas City (complete ballpark renovation in 1955) and in San Francisco (in order to relocate the New York Giants for the 1958 season). Major League Baseball officials would permit the Dodgers and Giants to move in tandem, if at all, and it was O’Malley who mentioned to Giants’ owner Horace Stoneham to explore San Francisco instead of Minneapolis-St. Paul. The two teams’ longtime rivalry would continue, while scheduling and air travel to the West Coast would be more feasible and less costly. When the City Council passed the September 17, 1957 resolution, 11-3, to offer a definite deal to the Dodgers, Wyman spoke of the fact that the Dodgers would not increase taxes in Los Angeles, but would put the hilly Chavez Ravine area on the tax rolls. Since the dissolution of a public housing project in the early 1950s, in which the residents received compensation through the public court system for their properties, no tax revenue was being generated on the property, despite a few residents who were living illegally there. The City of Los Angeles would initially receive nearly $350,000 a year in real estate taxes (which continued to increase beginning in 1963) from Dodger Stadium.

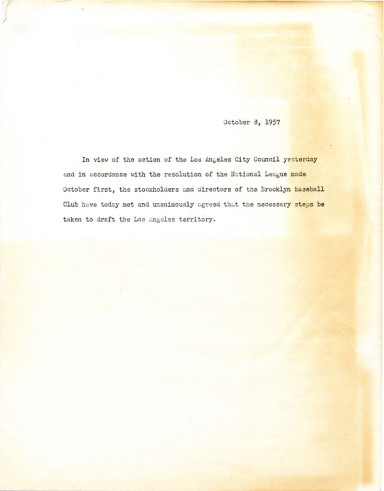

Press release and announcement made by the Dodgers on October 8, 1957, the day after the Los Angeles City Council voted to enter into an agreement with the Dodgers and asked them to relocate.

As part of the negotiations for the land on which to build and maintain the ballpark, O’Malley was legally bound to privately finance and construct 50,000-seat Dodger Stadium. Also, the Dodgers exchanged land at Chavez Ravine for Wrigley Field, which O’Malley had acquired on February 21, 1957, with its estimated value of $2.2 million. Additionally, O’Malley was contractually obligated to fund a youth recreation area near the adjacent Police Academy with an initial investment of $500,000 plus annual payments $60,000 for 20 years.

Prior to the council’s final vote on October 7, Wyman spoke with O’Malley on the telephone, as a nervous Mayor Poulson was unable to talk to him and handed her the phone. Although O’Malley never told her officially he was going to accept the Los Angeles offer if voted favorably by the City Council that evening, Wyman was not asked by fellow members and she did not relate that O’Malley never said for certain he was headed to Los Angeles. The council adopted ordinance 110204 that night by a 10-4 margin. The next day, the Dodgers announced, “In view of the action of the Los Angeles City Council yesterday and in accordance with the resolution of the National League made October first, the stockholders and directors of the Brooklyn Baseball Club have today met and unanimously agreed that the necessary steps be taken to draft the Los Angeles territory.”

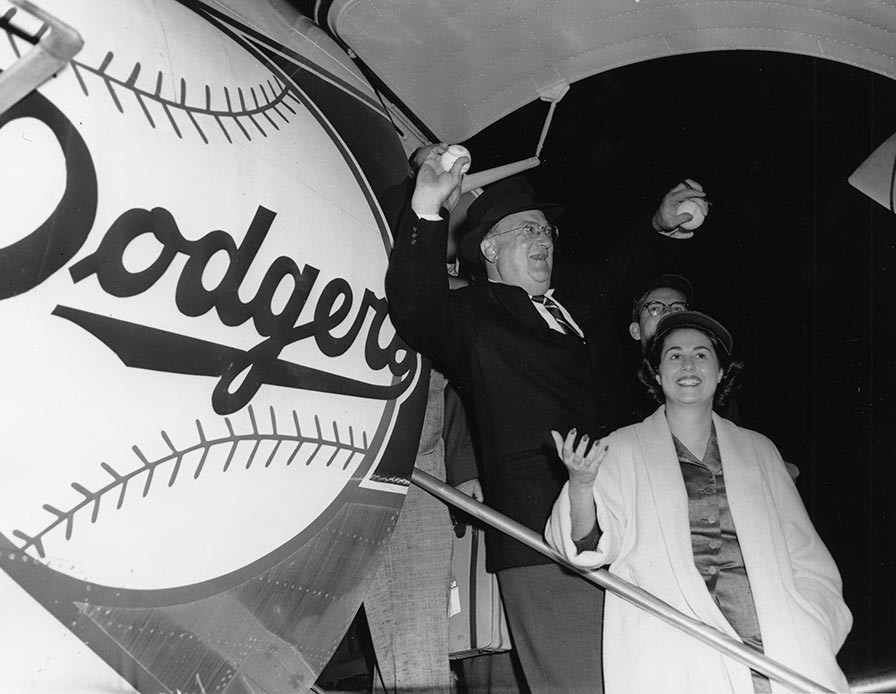

Wyman had a feeling of unbridled exhilaration and accomplishment, as the Dodgers, one of the most storied franchises in baseball history since 1890, were packing their bags for Los Angeles and the 1958 season. She was one of the members of the official welcoming party which greeted the Los Angeles Dodger Convair-440 airplane at L.A. International Airport on the chilly night of October 23, 1957. Several thousand cheering fans met the plane on the tarmac, most of them friendly, but not all.

The Dodger Convair 440 arrives in Los Angeles for the first time on October 23, 1957 carrying club executives and select players as the welcoming committee and fans are ready to greet the Dodgers to their new home. Bump Holman had “Los Angeles” painted on the plane in Vero Beach, Florida prior to traveling to New York to pick up the traveling contingent and flying to Los Angeles. The Dodgers arrived more than two hours late for the festivities due to strong headwinds which necessitated a fuel stop by Capt. Holman, but it did not put a damper on the celebration as the bands played and the big crowd properly welcomed the traveling party.

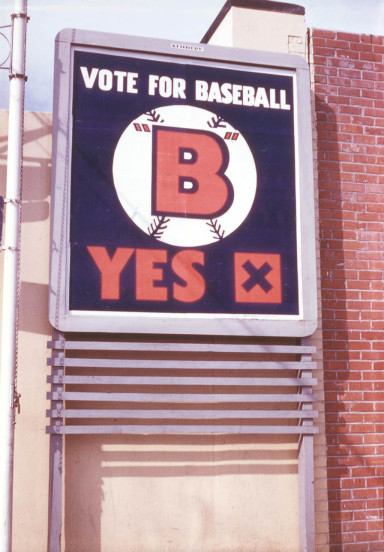

Elation would turn to frustration as a damper was put on the Dodgers’ arrival when a group of dissidents rallied support for a petition by the end of 1957, forcing a referendum known as “Proposition B” on the June 1958 ballot. A “Yes” vote meant the contract between the City of Los Angeles and the Dodgers was to be approved and in force, while a “No” vote rejected the previously signed contract. Sentiment was running high in both camps and O’Malley was caught in the middle of the politics, even stating, “I was not aware of a thing called a referendum. We don’t have them in New York.” Boston Globe, Sports Plus, July 28, 1978 Wyman would comment years later, “We didn’t know who was supporting the opposition. It took us a while to figure it out.”

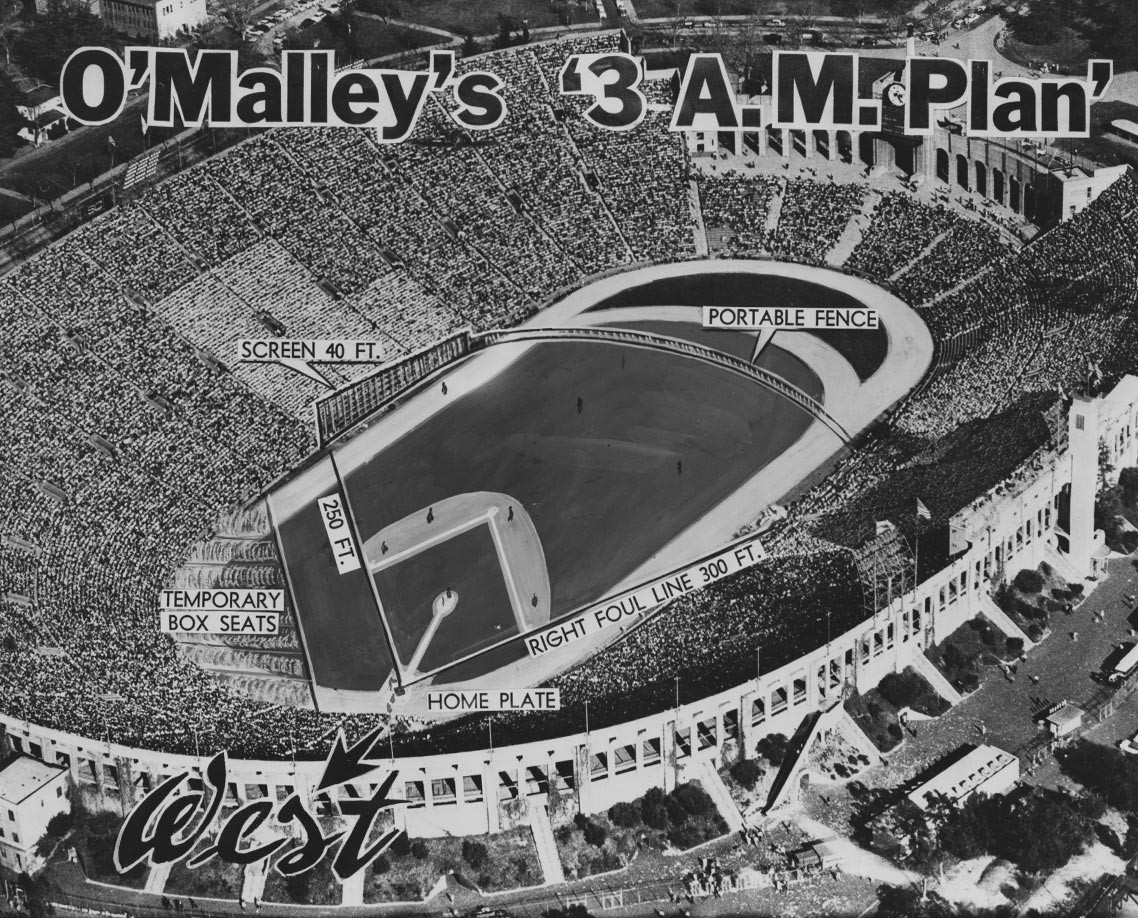

Even as O’Malley and the Dodgers struggled with a temporary place to play in Los Angeles when the team first came west, “Proposition B” might have derailed all of his plans. However, as the city representative for the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission, Wyman again stepped forward and was most influential as one of the prime leaders for the City of Los Angeles in resolving that issue. While the Dodgers briefly explored the possibility of playing at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena and rejected Wrigley Field because of its limited seating capacity (22,000) and even more inadequate parking, only the massive Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum remained as a viable solution. But the Coliseum did not come to the Dodgers without major modifications and an initial cost to them of $300,000, plus $600,000 for rent in the first two years, for laying out a baseball field in a stadium designed for football and track and field. With the Dodger rental fees, the Coliseum redid its seating, adding backs for the first time. Also, the first outside escalator was added, among other improvements.

A newspaper article with photo discusses how Walter O’Malley devised a plan at 3 a.m. on how to place a major league baseball diamond within the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The result was a short left field wall, 250 feet down the line, with a high 40-foot screen to run far into left center field to reduce short distance home runs. In addition, there are large power alleys to right center and right field. The concept was to get the approval from the National League to play baseball in the Coliseum, which the Dodgers did from 1958-1961, including a World Championship in 1959.

Wyman and Mayor Poulson assisted in designing a plan to use this alternative site, which for baseball held more than 90,000 fans, while the hurdles mounted in efforts to begin construction of Dodger Stadium. Legal challenges kept popping up, even as O’Malley and his broad-based band of supporters were able to face each one head-on. A five-hour “Dodgerthon” television program on KTTV Channel 11 in Los Angeles was aired on June 1, 1958 to explain to the public the benefits of voting for “Proposition B.” Wyman was one of the spokespersons who talked about the societal importance of bringing the Dodgers to Los Angeles and why voters should pass “Prop B.” A crucial 1-0 Dodger victory in Chicago’s Wrigley Field prior to that evening’s Dodgerthon helped to build momentum for the “Yes” side.

Two days later, the public favored the City’s and Dodgers’ position passing “Proposition B” by 25,785 votes in the largest non-Presidential election turnout in Los Angeles history, as 62.3 percent of the city’s 1,105,427 registered voters cast ballots.

A billboard in Los Angeles for Proposition “B” to support the contract between the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Dodgers. The contract provided for a mutual exchange of land and the payment of real property taxes by the team, an obligation that exists today. The land the Dodgers acquired became utilized for Dodger Stadium.

Still, a series of legal challenges faced the Dodgers and the city, while O’Malley was forced to delay plans to begin construction of Dodger Stadium. In one case, the California State Supreme Court unanimously (7-0) overruled a lower court decision and sided with O’Malley and the City of Los Angeles. The decision stated that the city could “hold harmless” the “public purpose” clause of the Housing Authority agreement deed restrictions (referring to the failed public housing project in the early 1950s slated for the land). On February 11, 1959, the California State Supreme Court reaffirmed its earlier decision in a refusal to reconsider. More challenges were made in April 1959 before an appeal was made to the United States Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the appeal on October 19, 1959, ending further review. Meanwhile, on September 17, 1959, O’Malley decided to proceed with groundbreaking ceremonies for Dodger Stadium.

With that obstacle cleared and the start of construction on O’Malley’s dream stadium for the Dodgers underway, Wyman helped focus the members of City Council, four of whom had voted against the contract, on the issues presented by the city’s planning director and zoning administrator. Additional roadblocks by those individuals, which would have delayed the construction process for another six months in fall 1959, were resolved by Wyman, who identified a solution to impose a “conditional use restriction” on the Dodger Stadium land. This significantly expedited the planning and zoning problems and permitted O’Malley to immediately secure financing.

Members of the Los Angeles City Council in discussions with the Dodgers: (L-R) John Holland, Harold Henry, Patrick McGee, Karl Rundberg, Ernest Debs, Jim Corman, Ransom Callicott, Gordon Hahn, Everett Burkhalter, along with Dodger Counsel Henry J. Walsh, and Councilwoman Roz Wyman.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

In the meantime, Wyman spoke to the Downtown Business and Professional Women’s Luncheon Club on October 22, 1959, stating the fight for the Dodgers was “the battle of the century” and that they were “good for the city.” Wyman also expressed her support for all of the arts and urged City Council approval for The Music Center in downtown Los Angeles as an example of another good business proposition and a place for another kind of entertainment. Norman H. Goodhue, Los Angeles Times, October 23, 1959, “Wyman Cites Value of Music Center”

She was also the driving force behind the Minneapolis Lakers move to Los Angeles in 1960, as a member of the L.A. Coliseum Commission, because of her friendship with Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey. He informed her that Lakers owner Bob Short was ill and searching for a new home (the Lakers split time in two Minneapolis arenas) because of sagging attendance. Short recognized the early success of the Dodgers on the West Coast.

Councilwoman Roz Wyman buys tickets for the St. Louis Hawks-Philadelphia Warriors basketball game at new Los Angeles Sports Arena on September 30, 1959 from Arthur Pollack, chairman of the L.A. Newspaper Publishers Association. Wyman was also instrumental in bringing the Lakers from Minneapolis to Los Angeles.

Born Rosalind Wiener, the native Angeleno is the daughter of Sarah and Oscar Wiener, who operated a family drugstore on 9th Street and Western Avenue in Los Angeles. Democratic politics ran in her family, as her mother was a precinct captain for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first presidential campaign. Wyman graduated in 1948 from Los Angeles High School, where she was the first girl elected as a student body officer. The talented and well-rounded student also played the French horn in the orchestra. She then graduated from USC with a B.S. degree in public administration in 1952. Her first taste of politics came in 1950 as she campaigned in California for U.S. Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, who failed in a bitter battle for the U.S. Senate to Rep. (R-CA) Richard Nixon. Douglas was the first woman to run in a statewide election in California.

Roz Wyman’s parents Sarah and Oscar Wiener, shown here on their honeymoon in Catalina, California, operated a family drugstore on 9th Street and Western Avenue in Los Angeles.

Determined, after the Douglas campaign, Wyman’s goal was to see a woman elected statewide in California so she has chaired all of Senator Dianne Feinstein’s campaigns for the U.S. Senate. Wyman got to achieve her goal. She also presided over the 1984 National Democratic Convention where Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman nominated for Vice President of the United States.

By 1953, Wyman shunned entrance to law school for a chance to campaign for Adlai Stevenson. “I fell in love with Stevenson as a candidate,” she said. “I wanted to be in his campaign.” Wyman, who would have had to take tests again and re-apply for law school admission, decided to enter into politics and, surprisingly, was elected as the youngest council member in the history of Los Angeles at 22 years old. The bold headline in the newspaper exclaimed, “IT’S A GIRL”. She represented the City’s Fifth District and would serve for the next 12 years, working on committees such as finance and budget, recreation and parks, and later became President Pro-Tempore.

Eugene and Roz Wyman in the 1950s.

Proud parents Eugene and Roz Wyman are all smiles on the birth of daughter Betty Lynn on April 5, 1958. Thanks to Councilwoman Wyman’s leadership, the first Dodger game played in Los Angeles took place on April 18 at the Memorial Coliseum.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Roz and Eugene Wyman are all smiles and the proud parents of newborn son, Robert Allen, at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital on January 17, 1960.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

On August 29, 1954, she married Eugene Wyman, a prominent Beverly Hills attorney, who became the Chairman of the California Democratic Party and Democratic National Committee Man. Together, they were leaders in fund-raising efforts and campaigns for Democrats in the state. Her idea of moving John F. Kennedy’s noted 1960 “New Frontier” campaign speech from the L.A. Sports Arena to the vast neighboring Coliseum was a stroke of genius, attracting 56,000 spectators to the venue, which appeared full on television, and magnified its status.

Of that night, she said, “I was part of a decision to take the convention outdoors to the Coliseum — the first time since FDR’s nomination at Soldier Field in Chicago in 1932,” said Wyman. “I was sitting with Bobby Kennedy and (Chief Political Strategist assigned to California) Larry O’Brien in a room. The Coliseum held 100,000, and they were dubious. ‘This will be great, we’ll let everybody come, instead of making it so closed,’ I said. Bobby turned to me and said, ‘If we don’t get the people, I don’t want to talk to you again and it will probably be the end of your political career.’ But we did. Every labor union and every Democratic club I ever knew in my life had been called. And it turned out really phenomenal, a great moment.” David Evanier, The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles, July 28, 2000, Cover Story

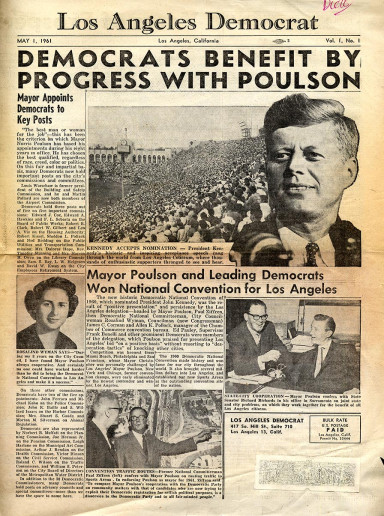

Los Angeles Democrat newsletter of May 1, 1961 reviews the 1960 Democratic National Convention rally at which candidate John F. Kennedy gives his acceptance speech for the presidential nomination. Roz Wyman suggested that the rally and nomination be held outdoors at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, instead of indoors at the L.A. Sports Arena, and the risky idea proved to be an overwhelming success.

Since 1952, Wyman has served as a delegate for every Democratic Convention (except in 1968 when her husband attended). Delegates are part of the official nominating procedure and vote for or against the party’s platform.

Wyman’s husband of 19 years passed away suddenly in 1973, leaving her to raise their three children (Betty, Bob and Brad) and continue her career. A former Los Angeles Times Woman of the Year, Wyman remains active in politics and the Democratic National Committee. In 1983-84, trailblazer Wyman was appointed and served as Chairperson and CEO of the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. Since the 1980s, Wyman has served as a Super Delegate at the Democratic National Convention.

Wyman still gets satisfaction from attending games in her season ticket seats that she purchased behind the Dodger dugout at Dodger Stadium, knowing that she helped shape Los Angeles history by bringing the Dodgers to the West Coast. Additionally, in July 2003, a Little League baseball field at Cheviot Hills Recreation Center in Los Angeles was named in her honor “Roz Wyman Diamond.”

She enthusiastically names her favorite Dodger player of all-time as left-handed Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax. “My family, politics, arts and sports are my life,” said Wyman, who is also involved in numerous charitable causes, such as “A Place Called Home” in L.A. which serves inner city children and the Executive Committee of The Music Center, which serves the city arts (theatre and music, including the Walt Disney Concert Hall). The gracious Wyman, the last living city official from Los Angeles directly involved with the negotiations to bring the Dodgers west, discussed with www.walteromalley.com her interaction with O’Malley in the following questions and answers.

Los Angeles City Clerk Walter C. Peterson and Roz Wyman conduct swearing in ceremonies for her third term as L.A. City Councilwoman in the Fifth District on June 24, 1961. Even Wyman’s children Betty and Bob give an assist during the official oath in City Hall.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

What are your special memories, as you reflect on your efforts as the youngest councilperson in city history to bring the Dodgers to Los Angeles?

“I think the most incredible thing that stands out is, first, we never thought we would get the Dodgers. The Brooklyn Dodgers aren’t going to leave Brooklyn. Why would any team leave New York City? That was number one. And number two, I felt as an elected public official, I was really doing something for my city. Some of the fights later were hard to believe. I felt that I loved sports, which was very strange being the only woman on the council. I probably loved sports more than all 14 of the council members put together. I went to the Hollywood Stars (PCL) and the (L.A.) Angel games and I don’t think any of them ever went unless there was some reason, some special event.

“I did a survey that showed that the corporations and the businesses wanted to come to communities that had sports and arts. They wanted these things. If you had people who wanted to come from other parts of the country, they wanted to feel where they are going to move and where they’re going to live, you are offering them everything. So, again, my survey proved...look here it is in black and white, this is good for the growth of the city of Los Angeles. It was a big growth period for Los Angeles. We’ve changed so much as a city since then.

“I thought that this great city of L.A. was getting a Los Angeles County Art Museum and was going to grow up and I didn’t understand how we could be a great city without having a major league baseball team. The motivation was it was good for my city and I also thought, obviously, it was very good business for my city and, therefore, I thought that it brings more tourists or tourists have something to do when they come here. When you got major league baseball, you could go see the Cardinals or you could go see every other team, as well as the home team. We were showing them the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League and they weren’t stars. Everybody thought just stars were playing for them when they came here, which was really funny. You’d get a question, oh Hollywood Stars do they go and play on that team? Some tourists would think that because they were called the Hollywood Stars. They weren’t that great. Once in a while you get a pretty good turnout, but it wasn’t big league.”

You first corresponded with Walter O’Malley in 1955 to meet with him in New York. Were you surprised by his response that his efforts were focused on staying in New York and he did not want to meet with you and Councilman Ed Roybal? How did you re-group from his response?

“I was really mad, to put it mildly. What I really thought was is he just positioning himself in New York then for negotiation with the land where Shea Stadium would eventually go or was this all talk about the Dodgers moving? I thought that it was pretty rude, to tell you the truth, the way you answer two elected officials. I thought is this a publicity stunt or something. I felt O’Malley had dealt too long with New York politicians and we were a little different out here. There were no Tammany bosses and there was none of that in L.A.

“Basically, I thought in a way, the Dodgers don’t want to move, they are really not interested in coming and how do we ever get the Brooklyn Dodgers? I thought his focus must have been to build his stadium in Brooklyn. And then, I also was sad because I always felt had he seen Eddie Roybal, I would have more cooperation from Ed Roybal, who was really my friend. We brought in the most unpopular motions and when I needed a second, I usually could get Ed because we pretty well stuck together. I thought that was really not smart (O’Malley’s declining to meet them). As it turned out, Councilman Ed Roybal represented the area where Dodger Stadium would be located.”

Walter O’Malley stands with LA County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn (background) and City Councilwoman Roz Wyman upon the arrival of the Dodgers in Los Angeles on October 23, 1957.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Do you recall your first meeting with Walter O’Malley and the circumstances?

“I didn’t meet with Walter O’Malley until the team came and I was on the steps to the airplane (October 23, 1957). That was the first time that I ever met him. It just seemed like I was always away when he showed up (on three previous trips) and (L.A. County Supervisor) Kenny Hahn would report to me, because Kenny Hahn and I clearly were the strongest two for major league baseball. He told me, obviously, and the papers were full of when O’Malley flew over Los Angeles in a helicopter and for the first time saw Chavez Ravine and other areas that might be considered for his stadium and that leaked out to the press. I’m not sure that was the greatest leak...we probably could have done without that leak. I kept in touch, but each time I missed O’Malley. I never met him until I met him on the stairs going up to welcoming him to Los Angeles and the process server ran up the stairs and Walter leaned over and said, ‘What was that?’ and I said just accept it, I’ll explain it to you later. And was he shocked when we walked away down the stairs. I said you have just been served Mr. O’Malley. He was a lawyer and he certainly understood what that meant. I said there may be a few lawsuits. I never talked to Walter O’Malley until the day of the final council vote (October 7, 1957).”

In view of the failed bond measure to help fund a baseball stadium in Los Angeles in 1955, after listening to Walter O’Malley’s desire to privately build and maintain his own stadium were you more or less encouraged that you, Mayor Poulson and others would be able to convince the Dodgers to come westward?

It was encouraging and it was interesting, because all during my arguments I could use that he wanted to build and finance his stadium. Here’s a guy who wants to build his own stadium. Because all across America, the ballparks were being built and all taxpayer money was being used to pay for them. But that was a negotiating point as far as I was concerned, because at one point during the negotiations they kind of threw up their hands and said okay we’ll take the deal in San Francisco and I said over my dead body you will. Because, I wanted that stadium to be privately built, because then it could be taxed. If it was a municipal stadium, we could not tax them and that was a huge issue for me all the way along and I never budged on that issue. I didn’t think that bond issue would go to begin with or be close. Some of the powers said let’s put a bond issue out and maybe we can entice a ballclub. That was defeated and I was happy.

“A lot of people say it’s great to own a ballpark. What for? It was a one purpose use at that point. You put it all together and I didn’t want the upkeep and the maintenance. I had been on the (L.A.) Coliseum Commission and I knew what the maintenance was over at the Coliseum Commission. People say we should own it and I don’t know why we should own it. I never thought we should own it. San Francisco went into a municipally-owned stadium (Candlestick Park). It never compared to Dodger Stadium. It was never maintained (cleaned and landscaped) like our stadium.”

In 1959, Councilwoman Roz Wyman stands in front of a microphone with pins in her hand that read, “Let’s Go Big League L.A.”

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

A lifelong baseball fan, Roz Wyman gets her chance to take a swing at the Griffith Park playground in a game with day campers on July 20, 1960.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Roz Wyman and fellow Los Angeles City Councilman Edward Roybal choose up sides for a softball game on the Griffith Park playground with day campers on July 20, 1960.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Were you the one that initiated the discussions about Major League Baseball for Los Angeles?

“I don’t know what happened before I got there (in 1953), but I do know that I had a little piece of literature. It was a little 3 x 5” card. I had no money when I ran the first time (for City Council). Literally, I walked from door to door and I got elected by walking door to door. And in those days, it’s almost like the (literature was the) size of a business card. We used to get 35,000 of those in those days for about $30. I had checked off on the piece of literature one of the points Bring Major League Baseball to L.A. when I ran. My Mother and my Mother’s side of the family were baseball nuts. Her brothers had played baseball in a neighborhood league. In Chicago, they just loved the Cubs. My Mother always talked about the Cubs. I was born during the World Series. It had an effect on all of us. My Mother wanted to know what the score of the World Series game was. She didn’t ask if it was a girl or a boy, but wanted to know the score of the game! My two uncles played ball. I can’t say semi-pro, but maybe a level under it. They went every week (to play) or sometimes they went on a bus to another city. So, baseball was in my Mother’s side of the family. She talked about baseball. We would go to the Hollywood Stars a lot. My Mother went. My Dad never went. My Father had no interest whatsoever. My Mother and Dad were both druggists...Mom and Pop druggists. Both my parents were learned. My Mother was really into sports and my Father into reading medical books. He wanted to know the newest medicine, or he wanted to read Shakespeare, or he wanted to go hear opera and we (Mom and I) wanted to go to the ballpark.”

Who was your favorite baseball team when you were growing up in Los Angeles?

“It had to be the (Chicago) Cubs at that moment because of my family. Then when I got married, my husband was a St. Louis Cardinals fan. I mean he was Stan Musial day and night, night and day. I’ll never forget sitting with Walter (O’Malley) the first time that Stan Musial came up and I thought, oh, oh Gene better be quiet. He’s going to say something in front of Walter...I hope he gets a hit or something. The first year Gene didn’t say anything. The second year was fascinating to watch Gene. Stan Musial was the batter and Sandy (Koufax) was pitching and Sandy struck him out and Gene said ‘Hooray!’ And I said, wow, it only took us a year to convert him. So, he switched.”

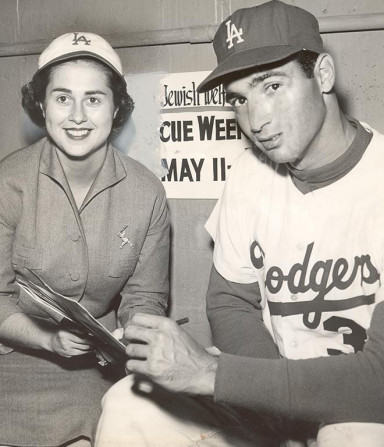

On May 10, 1959, Roz Wyman and her favorite player Dodger left-handed pitcher Sandy Koufax team up in the Dodger dugout at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum to assist the United Jewish Welfare Fund’s “Rescue Week.”

How much influence did Mayor Poulson have in eventually bringing the Dodgers to Los Angeles? Has he received enough credit for supporting the idea and a location for them to play?

“Let me just say I was very fond of Norrie Poulson and he was a right-wing Republican. For me to be proud of, and friends with, him was pretty weird. He was as right-wing in Congress as they came. But, as Mayor I really felt he was kind of a different person. We didn’t have the issues you have in Congress, luckily. Poulson originally, I have to tell you, was dragged into the Dodger controversy. He was very apprehensive. He thought the people of L.A. had voted a bond issue down and asked, ‘Why do I want to stick my neck out? I don’t know these Dodger people.’ Poulson ran around with the ‘in-crowd’ of downtown which I didn’t, by the way, except Otis Chandler, when he became publisher of the paper (L.A. Times) and we were very good friends. I spent a lot of time with Norrie on this and said Norrie I think it’s really popular with the people. But, then we had all those lawsuits and we had the (Prop B) referendum, he would sometimes get me by the side and say, ‘Yeah, you’re sure right, the people really like this thing.’

“We were getting really bogged down between the City Attorney and the council -- Sam Leask, the Chief Legislative Analyst who answered to the Mayor, and the city’s Chief Administrative Officer who answered to the council. We were getting a hassle between all of those people and what Norrie did, which was the best and most helpful thing he did, was to find Chad McClellan (who was lead negotiator for the City and County of Los Angeles and President of Old Colony Paint). And Chad basically saved our lives. Chad came in with his fine reputation and as a big corporate guy, right down the alley of all the key downtown boys and Poulson. I don’t know if he was recommended but Norrie came to us and said, ‘I think he might be helpful’ and I said Norrie anything will be helpful. We were just bouncing all these people, back and forth. Then we had O’Malley represented by (Dodger Vice President) Dick Walsh and by his (O’Malley’s) brother-in-law Henry Walsh. Henry was a very able lawyer, a very lovely man. Dick was a good representative and, at the same time, a very considerate person. But, it was at that point, they had never dealt with government and they couldn’t understand if I said something, how come it didn’t happen? Or, if Roger Arnebergh, the City Attorney should say, ‘This is the way it should be’ well why didn’t it happen that way?

“We had too many cooks at that point and Chad helped to straighten it out. We never would have gotten the negotiations where they were if we hadn’t had an independent person from all the elected officials to help us. And we picked somebody who was very well respected in Los Angeles. He was really smart; he went around and introduced himself to all the people involved in the city that he would have to work with. He didn’t just plunk himself down and say here I am. At this time, I also was in my first pregnancy. And then more — the referendum and everything else.”

Walter O’Malley and Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson meet with several members of the Los Angeles City Council, including (standing L-R), Ransom Callicott, Roz Wyman, Ernest Debs, Jim Corman and (seated L-R), Everett Burkhalter, Karl Rundberg, John S. Gibson, Jr. and Gordon Hahn.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Why did you feel so strongly about the need for a Major League Baseball team in Los Angeles? The Pacific Coast League already had teams playing in L.A. and Hollywood and was not overwhelming attendance-wise.

“Everybody had huge heroes in baseball. You talk about the kids. You were going to get Stan Musial and you were going to get some really great players that people had certainly heard about. I mean the Dodgers certainly had them — Duke Snider, Carl Furillo and Gil Hodges. As I said, almost to the very end, I didn’t think the Brooklyn Dodgers were going to leave Brooklyn. That was one thing, I’d come home and my husband would say ‘Well, what do you think?’ and I’d keep saying deep down I keep thinking they won’t come. I mean, how do you leave Brooklyn? Although I knew Ebbets Field was built in 1913. But, the tradition and the O’Malleys are such New Yorkers. I always deep down had this feeling in the pit of my stomach that after I beat my guts out that they would not come. That was a real fear.

“But, I did feel that all of those reasons that it would be great and I had seen some of things that the Brooklyn Dodgers had done and Major League Baseball about encouraging Little League and some of the things that various clubs had done across America and, I thought, yes we have some of this, but the Hollywood Stars and the Angels were doing nothing with clinics or Little Leagues.

“I also felt very strongly the biggest motivation was my city has to grow up. It was good business, it was good for tourism and if I got them to build it, I could tax it and I could prove to the people that they kept their word and built a first-class stadium. These were honorable people and it would be really good for Los Angeles and that there were no unifying projects. All parts of Los Angeles watched Dodger Stadium being built and, therefore I always felt and I’ve said this a hundred times over, that the day (the Dodgers won the 1959 National League Pennant in Los Angeles against Milwaukee) that (Vin) Scully said, ‘We go to Chicago!’ horns started tooting all over the city...it was the first time, the eastside, the westside all came together because they saw this grow in front of their eyes. You saw them come and people became a part of it. Three million people go out there every year. They don’t have to go. They don’t have to buy a ticket. I’ve always felt that it cost me a lot politically, but that I still felt that it was the right thing to do even as I look back on it now.

“I might have been Mayor had I not led the battle for the Dodgers to come West. It may have cost me that, but I still feel it was one of the best things that ever happened for Los Angeles. People today don’t remember how controversial the battle was and therefore it was used as an issue to defeat me in my last election. (Prior to that, in polls it showed Wyman had a 90 percent approval rating in the city.) It’s interesting to note that in the Los Angeles Business Journal of May 23, 2005, Dodger Stadium is listed as a “Turning Point” and one of the “Ten transactions that played a role in L.A.’s rise to world-class status.”

Roz Wyman shares a happy time amongst renowned movie producer Mervyn LeRoy (left), entertainers Jack Benny and George Burns and actress Pat Mowry at the June 1, 1958 Dodgerthon produced by KTTV Channel 11 in Los Angeles.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Weren’t you also extremely concerned about growing Los Angeles in many other areas to the point that you challenged your fellow council members on them, as well?

“I was very supportive of arts for the city. Our first cultural accomplishment that finally came about was the art museum on Wilshire (Blvd.). I thought great we finally got an art museum. I was big on the arts. I mean I fought for all kinds of art. I also felt we were pretty little league in arts. Dorothy Chandler and I became friends, we didn’t start out friends, but we became friends. In people’s minds, I was this liberal democrat as far as they were concerned. I was way out in left field. City issues didn’t fall into liberal and conservative. They are much more partisan today in a City Council than when I served. We really had the opportunity to grow as a city. I supported Dorothy Chandler from day one and the Music Center. It took her a lot to build it. I just thought once the Music Center was also up and we had Dodger Stadium you could see the growth of a great city. Now look what we have with Walt Disney (Concert) Hall. A major city is a major city and you have everything to offer or you don’t. I cared deeply about the arts and that was another thing that most of the council couldn’t care less about. I also felt Los Angeles didn’t care about the development of a fine park system. Los Angeles had great climate and yet other cities had greater parks than we had and I also felt that we could have pocket parks to serve various areas of L.A. — just a little green to sit in. I mean sports and arts, you’d think it’s something they would care about, but they weren’t wild for that either. There are stories about me fighting for culture.”

On May 2, 1957, Walter O’Malley takes a 50-minute helicopter ride to view prospective sites for Dodger Stadium. From left is Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, Undersheriff Peter Pitchess, Del Webb, co-owner of the New York Yankees, O’Malley and pilot Capt. Sewell Griggers at Biscailuz Center.

When Walter O’Malley made his now famous visit to Los Angeles (only his third trip ever to L.A.) in May 1957 and took a helicopter ride over the city to view possible sites for the ballpark he wanted to build, was that a turning point in your mind?

“I felt it was hopeful. You see, I keep going back, I never thought the Brooklyn Dodgers would come. I kept thinking we’ve come a ways. Two years into this and he’s still dealing with New York. So, I had to look at it a little positive. And I thought, well, third trip, he keeps looking at the site (Chavez Ravine). I thought we’ve come a long way in a sense; that he’s now flying over L.A. I did feel there was hope. Kenny Hahn said he thought that trip was very positive. I don’t know why I wasn’t there. I remember coming back and Kenny calling and saying, ‘Roz we might have something positive.’ We may have! But, the sportswriters had developed good stories about this visit, which was helpful to me.

“Kenny and I were really close friends. Kenny was the youngest person ever elected to City Council. Then I came along and I was the youngest. There was already a bond between us. Kenny was very active in Democratic politics. Even though I was very young, I had fooled around in Democratic politics already. He really deserves credit for helping in bringing the Dodgers west. The trouble was it was a city responsibility and I had the brunt of it. He was for it, but the County didn’t have much to do with it. It just became my problem and Kenny was a rooter. We needed the County of L.A. to help with roads. Kenny saw to it that these were secured.”

You made a critical phone call to Walter O’Malley the night of the City Council vote on October 7, 1957. Apparently, Mayor Poulson was too nervous to talk to Mr. O’Malley about coming to Los Angeles and handed the phone to you. What do you recall about that conversation?

“It was crazy. We are up to the last day of the vote. We sit in a semicircle in City Council and my seat was the last seat alphabetically and there was a way that you could come into the Chambers through a door closest to my seat. The Mayor’s office called me and said the Mayor wants to see you. I said I can’t leave the floor now. We’re in the middle of this discussion and I don’t want to leave. The Mayor’s secretary said, ‘The Mayor wants to see you. It’s very important that he see you and he has some idea, that he wants you to do something.’ They called me three or four times. I said I’m not coming. I’m not leaving. I didn’t know what he wanted, but I said I can’t leave the floor right now. We were really in a critical time. I have got to listen to what’s going on here. I’m petrified that I am going to lose the vote anyway, (Councilman Karl) Rundberg’s vote, so I just didn’t want to leave. The Mayor comes running down the hall and the policeman opened the door. He’s standing about halfway through the hallway. He sent the assigned Council policeman to the Chambers to bring me to him.

“He said, ‘The Mayor is standing there and he wants to see you.’ I said for goodness sakes won’t he leave me alone? But, I said okay because he’s here and I could still hear the speaker box and I’m still standing close. I said what do you want Norrie? He said, ‘We have to call Walter O’Malley.’ I said why do we have to call Walter O’Malley? I said I haven’t talked to him all the way along, I don’t know if you’ve talked to him all the way along, I don’t want to talk to him. I said it will be dreadful to talk to him right now. Poulson said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I said, Norrie, what if he says no, I don’t want to come? What are you going to do then?

“I said his people are saying this is a good negotiation. That he will like this contract. I don’t want to talk to him because I feel I’m honest and if somebody asks me on the floor of that council, ‘Have you ever talked to him? Is he coming?’ What am I going to say then? He said, ‘You’ve got to call Walter now. We have to know his answer about coming to L.A.’ So, I gave in and went to the Mayor’s office. But, I’m still thinking this is stupid because if O’Malley says no then what do I do? So, he got on the phone and I said you talk first. Poulson said, ‘Oh no, I don’t want to talk at all.’ I thought at least he would start the conversation. ‘Oh no, no, here’s the phone.’ So, he wouldn’t talk at all.

“Now, I’m first introduced to O’Malley on this phone call after many months. I’ve never spoken to him. He said, ‘Mrs. Wyman, I want to thank you for all you’ve done.’ And he said, ‘I know it’s been difficult’ and he was very gracious. I don’t want to get to the question and I’m talking about the weather almost. You know, how’s the weather in New York? Finally, Norrie says ‘Ask him, ask him, ask him!’ I mean literally yelling at me, ‘Ask him, ask him, ask him!’ And I thought Roz don’t, but finally I thought I’ll never get out of this room if I don’t do it. So, I said Mr. O’Malley, I take it if we vote this deal through, you will come. And he said, ‘I do not know if I will come. I’m certainly seriously giving it consideration. Do you know if you have the votes?’ I said I think I have the votes. He continued the conversation, ‘I am a New Yorker. I still believe that possibly the better place for us is in New York.’ He said, ‘Baseball has never been very successful in California.’ He said, ‘I don’t know if we will come.’ At this point, I was so deflated, I thought why argue with him, as I had to get back to the Council Chambers. I said Mr. O’Malley, that’s a pretty disappointing answer. I said we’ve gone a long way to get here. I said, but I do have to go back to the City Council and fight this thing through. I said it was nice meeting and talking with you on the telephone. Goodbye.

“I was really devastated. It took me a little while, in fact, I went back to my office to really collect myself. I was really disappointed. I didn’t have time to get into my personal feelings. I had to get back to the floor of the council.

“I never deceived people in my career in the City of L.A. I thought will the council be smart enough to ask me, ‘Is he coming? Did I know for sure the Dodgers would come to L.A.?’ As it turned out, they never asked me and, if they had, I was concerned because I didn’t want to deceive my colleagues or the City of Los Angeles with my answer. If my answer was negative, that surely would have affected the vote which was coming very soon. I felt O’Malley wouldn’t have had a team negotiating if he wasn’t seriously considering coming to Los Angeles. That was the best I got from that conversation.”

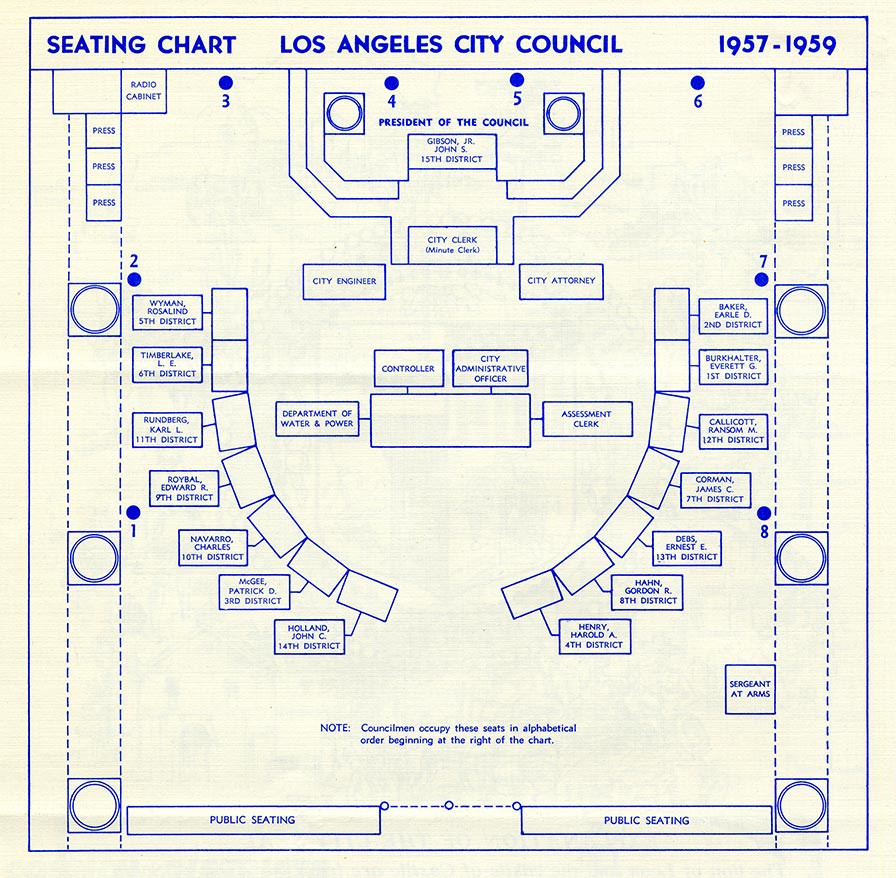

The seating chart for the Los Angeles City Council meetings shows that the council was seated alphabetically and thus Roz Wyman was by the exit door on the far left.

How long was it until the City Council voted that night?

“It was more than a couple of hours and I decided it was time to call for the vote. We went into an evening session, which was rarely done. We went quite late, after having debated all day. My biggest problem then was to hold Rundberg in (to get to 10 votes). There’s an old saying in City Council about voting, ‘I’m with you until roll call...then who knows?’ I called for the vote, still not sure of Rundberg. I decided we had discussed and debated this far enough. We were going to win or lose.”

When the Council voted 10-4 to approve the contract on October 7, 1957 with the Dodgers and ask them to relocate to Los Angeles for the 1958 season, did you have a great sense of accomplishment and relief?

“I was exhausted! I didn’t enjoy it at that point. I was absorbing what O’Malley had told me on the phone. We voted. I’m going to go home and hope O’Malley’s going to say yes the next day. The next day, October 8, the Dodgers announced they had drafted the Los Angeles territory according to the City Council terms and invitation. Now I had a sense of elation. I still didn’t understand why, if the Dodgers planned to announce the next day after our vote that they were coming to L.A., O’Malley didn’t tell me on the telephone conversation.”

Los Angeles City Councilmember Roz Wyman dons a baseball cap with the hand-printed words, “L.A. Bums” on it, October 7, 1957, the day of the City Council’s final vote to approve its contract with the Dodgers.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

Walter O’Malley (center) speaks to legendary New York Yankees Manager Casey Stengel at the city’s Welcome Luncheon for the Dodgers at the Statler Hotel in Los Angeles on October 28, 1957. City Councilmember Roz Wyman (left), Dodger Manager Walter Alston (standing) and Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson (right) look on. Unidentified man standing between Stengel and Mayor Poulson.

Los Angeles City Councilwoman Roz Wyman with pennant in hand, Walter O’Malley and Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson huddle at the dais during the official Welcome Luncheon for the Dodgers in Los Angeles on October 28, 1957 at the Statler Hotel.

Were you surprised by the unexpected fierce opposition that took place almost immediately thereafter?

“We were surprised that the opposition was well-organized. The opposition was well spread all over the city and we began to realize there was real money behind this effort. It took me a long time to figure out about J.A. Smith down in San Diego, who was behind it and trying to get a team that he would own there. Smith decided that there would never be another major league team to come because of the Dodgers. He knew the PCL would be gone and thought that they would never get a San Diego team. It took 11 years to actually get one. O’Malley and I often discussed with the P.R. firm Baus and Ross Company that this was a well-organized, funded campaign. The opposition had a lot of material handed out which was getting around the city. The signs that are wonderful are the signs that are homemade. All the signs and all the literature we saw were not homemade. We kept saying there’s money here somewhere. The funniest thing of all, my little Mother, who loved baseball, was sent by the campaign to some of their public meetings. We needed information. She got on their mailing list and would show up and she’d come home and say, ‘Rozie, they are really out to beat this thing.’ And she said, ‘They’re even doing a phone bank.’ It was just like a political campaign. My Mother knew something about campaigning as our drugstore was (Franklin) Roosevelt — (John Nance) Garner headquarters in 1932.”

A flyer that was used to explain the “Yes on Proposition B” Referendum vote in Los Angeles in 1958, meaning that the previously approved contract between the City of Los Angeles and the Dodgers would be honored and remain in force.

What were you doing to ensure that the opposition’s resolution, eventually on the June 1958 ballot as “Proposition B,” didn’t thwart the city’s contract and Walter O’Malley’s efforts to privately build Dodger Stadium?

“We weren’t moving fast but we were trying to move along, so we would be ready when all the legal challenges were finished. We were also a little nervous as was Roger Arnebergh, the City Attorney, who had worked out all the details regarding the contract to make sure the city met its obligations. Arnebergh was still dealing with the Referendum and lawsuits, which even went as high as the California State Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court (which refused to hear the case).”

Was the election as close as it turned out?

“It was closer than expected. O’Malley and I always said that had the Dodgers not won the day game in Chicago, 1-0 (on June 1, 1958), we would not have won. It is one of the most important (Dodger) victories ever. I don’t think it’s ever gotten its due. Vin Scully did not say how to vote, but he told people to go out and vote. I thought Scully was accepted by the City of L.A. immediately upon the Dodgers’ arrival and the fact he told people to vote was helpful. And to this day, everybody adores and sets Vin Scully on a pedestal. He has been always accepted by this community as a trusted spokesperson.”

If “Prop B” failed, what would have happened?

“I just felt there was enough goodwill between the City and the Dodgers and we could convince the City that it was good business for L.A. We would just have to find another way to get that stadium built. I don’t believe I would have ever given up after what we’d been through.”

An overhead view of Dodger Stadium and its newly-formed parking lots, which were functionally built to enable fans to enter the stadium on the same level on which they parked. This would minimize the need for vertical transportation and escalators, although those were added later.

Los Angeles Times Collection, UCLA Library Special Collections

When you first saw Walter O’Malley’s plans for Dodger Stadium, what did you think about his and architect Capt. Emil Praeger’s modern design?

“Loved it. I thought the contour of the land was well used. That impressed me a lot that he used what he had. I liked that part of it the most. I was very worried about the roads, because I thought we’ll never have enough money and will it work? I thought they were close to freeways and that would provide good access. I loved the plans from day one. And then when prominent Hollywood director Mervyn LeRoy made the (stadium) model it was a beautifully done job because the Hollywood artist knew how to do it. It was made from architect’s plans before the stadium was built. The model became useful to show people that this was going to become a great asset for the city. I continued to look at it as a good business proposition for the city and a lot of new jobs for them were created in the building of Dodger Stadium and many more new jobs when the stadium was in operation.”

All of the roadblocks that came in the form of the Proposition, legal challenges and the eventual dismissal by the U.S. Supreme Court, must have taken a toll on both you and Walter O’Malley. How did you find the strength to stay the course and eventually succeed?

“We sweated that out. If you are an elected public official, you’ve got to take the good and the bad. It also took a toll on City Attorney Roger Arnebergh. I didn’t think the Dodger issue would be so controversial when I said, ‘Let’s Bring Major League Baseball to L.A.’ I always enjoyed being an elected public official of the City of Los Angeles and I tried to be responsive to the people of the city. I had a wonderful husband who gave me incredible strength and support. People who knew Gene and me said if we had gone into a computer program, we would have come out perfectly suited for each other. When things were tough, he was always there. He was a good listener. I knew that even if I were not re-elected for City Council, I had a very good life ahead of me.”

In your many day-to-day dealings with Walter O’Malley, how would you describe your relationship with him?

“We became just wonderful, wonderful friends. His family became my family. I always said if I write my book, Walter would have a huge chapter. And he will probably be one of the most unforgettable persons I will have ever known in my life. Remember, I’m very active in politics nationally. Walter was a Democrat. Walter knew many Democrats from New York. We often talked about them. (Former Speaker of the House from Massachusetts) Tip O’Neill was one of my favorite people, a great Irish politico. Walter O’Malley was Tip O’Neill — storyteller, a hunter, loved good food and had an incredible sense of humor. This description also fit my dear friend Walter. Now, Walter and I love to eat ice cream. For my 40th birthday, Kay O’Malley went out to Baskin Robbins 31 Flavors and bought me 40 sundaes, which I happily put in my freezer! I mean we had so much fun in Walter’s box at Dodger Stadium. I often stood over in the right corner of that box and Walter used to sit on the end. We socialized and we shared. Walter used to say, ‘That’s Roz’s spot.’ It gave us a good chance to talk. We spent a great deal of time together so the O’Malleys and the Wymans were like family.

Walter O’Malley invites Los Angeles City Councilwoman Roz Wyman to attend a game at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Wyman’s love of baseball and the Dodgers led her to attend Dodger games both at the Coliseum, the Dodgers’ temporary home from 1958-61 and later at Dodger Stadium which opened on April 10, 1962.

Mervyn LeRoy (left) and Roz Wyman (right) join the celebration of the 30th wedding Anniversary of Kay and Walter O’Malley on September 5, 1961 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. A smiling Kay is ready to cut the cake while also holding grandson John Seidler.

Roz Wyman presents a proclamation to Kay and Walter O’Malley on the occasion of Walter being named “Man of the Year” by the Beverly Hills B’nai B’rith, a Jewish fraternal and charitable organization. O’Malley was officially feted on January 28, 1962 in front of a crowd of 1,300 well-wishers by an all-star cast of celebrities.

“Kay was just wonderful. We went up to Lake Arrowhead with them. We went on the boat together. We cooked together. He loved to cook and eat.

“The night before Opening Day we had a dinner (at Dodger Stadium). They were going to try out the organ. We were all invited to dinner at the (Stadium) Club and he said Roz would you come out — let’s say it was six — and he said would you come out at five. Well, why do you want me at five? What am I going to do out there for an hour? He said, ‘I just would like you to come.’ So, I said, Okay and told my husband, you go separately and I’ll meet you. Walter took me into his office and we sat down and he said, ‘I cannot thank you enough for what you have done.’ He said, ‘It is certainly a different life for us and it has changed our lives. And you have certainly been a huge part of it.’ He said, ‘I want to walk outside with you.” As we came out, the organist began to play and Walter said ‘That’s for you.’ The organist played a medley including ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game.’ Forty years later and that still brings tears to my eyes. And then we went to dinner. It was very special that he did that. When Walter died, Peter (O’Malley) sent me a key that was made to open every door in the Stadium. There were only two made. Walter had one and I don’t know who had the second one. When Walter died, they found the key and Peter sent it to me with a beautiful note and the note and key are framed and hung in my den. Peter said there is only one person who should have Dad’s key and that is you.

“The interesting thing is you do a lot of things when you are elected for office. You help a lot of people. Nobody was as gracious as the O’Malleys were. Obviously, the move of the Dodgers meant great success for the O’Malley family. I’ve been in politics 50 years and most people do not remember what you do for them especially when you are out of office. The O’Malleys always remembered me and my family because we became lifelong friends. It has been one of the most important friendships of my life. I also said if I could rear my children as nice as the O’Malleys had done as regards to Terry (O’Malley Seidler) and Peter, I would be a very successful mother.”

Roz Wyman is the rose amongst some famous stars sitting in “Campy’s Bullpen” at the Second Annual Dodger Dinner sponsored by the Los Angeles Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America on April 13, 1959. Back row are (L-R) Dodger catcher John Roseboro; St. Louis Cardinal Hall of Famer Stan Musial; Wyman; Dodger pitcher Stan Williams; Dodger shortstop and Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese; comedian and TV host Art Linkletter. In the front row are Dodger outfielder Carl Furillo and Dodger catcher and future Hall of Famer Roy Campanella, who was honored by a capacity crowd of 1,500.

Presentation made by Mrs. Rosalind Wyman, Los Angeles City Councilmember (at microphone in center of photo) on May 7, 1959, the tribute game for Roy Campanella. The game drew a then record crowd for a baseball game with 93,103 in attendance.

What do you feel the Dodgers have meant to the City of Los Angeles since they arrived in Los Angeles for the 1958 season?

“It was a project that unified the City of Los Angeles for the first time. I felt the city had been a part of the new project and as it turned out was excited about it. I knew that to be true. I always felt the first thing that I was so proud of was when Scully said (after winning the 1959 National League Pennant in Los Angeles by defeating Milwaukee), ‘We go to Chicago,’ you felt a rooting for something. We found that once we had the Dodgers and then the arts, the corporations and the small businesses wanted to come to Los Angeles, too. Our city became big league.”

What about O’Malley’s involvement in the community?

“When the O’Malley’s moved here, they really embraced Los Angeles. They came here to live. They came to put roots down. They became a part of the community and he became well known. Hollywood really embraced the Dodgers in a big way. We had the Hollywood Stars game in those days and they were Hollywood Stars. You would have Milton Berle, Sammy Davis, Jr., Dean Martin, Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra all involved with the annual event, which the fans just loved. It was big. The stars loved the Dodgers and they loved Walter. Walter would have numbers of them in the box...Milton, Danny Kaye, Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell, Lauritz Melchior. In other words, Hollywood became a part of the Dodgers and Walter, not that he ever was considered “Hollywood,” was fun for them.

“Walter was a storyteller, he was a great host. Walter loved that (president’s) box. He loved to have people for dinner and he schmoozed with them, talked with them. But, I must say sometimes at the game, it was very serious. We had to win this game. But, he had the philosophy, ‘Roz, that’s one game. There are 80 some more. We cannot die over each one.’ I would die over every one. He’d say, ‘There’s another day.’ And he was the best sport, and always optimistic, as was Peter, if the Dodgers lost, I must say. It was really quite incredible. Those who knew him and those who spent time with him would say I had the best time with Walter. He was a person’s person. He loved people. It just showed. It came out all over him. I was with him hundreds of times. I always had a good time.”

“Because of the Dodgers, it made Walter a big part of the community. But, I know that Peter O’Malley has had a much more active community participation. Peter helped enrich the Dodger (Community) Foundation, Jackie Robinson Foundation, Little League Baseball, both locally and nationally, and his activities with The Music Center of Los Angeles. Also, I believe we would have had a NFL team here if we would have followed the plan Peter had for L.A.”

Roz Wyman watches an exhibition game at Holman Stadium during Spring Training at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida in March, 1959.

When did you go to Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida?

“My first trip to Vero Beach (in 1959) with Walter was something. Stanley Mosk (California State Attorney General and later a justice of the California State Supreme Court) and I were there. It was the first time Roy Campanella had been to Vero Beach since his automobile accident (which left him paralyzed from the neck down). When he was taken from the airplane, there was utter silence because people realized that one of the greatest ballplayers of all time would play no more. I’m sure it reflected by those baseball people around him that careers are so fragile that you just don’t know what life will bring. As it turned out, Roy Campanella was an inspiration the rest of his life for people who saw him or had the privilege to know him.

“We had barracks (to sleep in) in those days. O’Malley said, ‘Oh, you’ll love it here Roz.’ The first night I said I’m frozen. He said, ‘Roz you have got to go out and get fresh orange juice. We have a machine here. He was so proud. ‘We have this machine that makes it, you get it fresh.’ So, I go outside and it’s frozen! Frozen! I go back in and said Walter it’s frozen. He says, ‘Oh. We’ll get the thing (working right).’ There was no heat in the barracks. I’d say Walter I’m freezing. He’d say, ‘Here, here’s a sweater. This makes men out of them.’ But, I’d say, but I’m not a man! Walter I’m freezing down here. There is a picture of me with Don (Drysdale). I called my husband Gene and said I just hit a pitch that Don Drysdale pitched to me. He said, ‘You are making up a story.’ I said I have a piece of film and I’m bringing it home to show you that I hit a pitch that Don Drysdale threw. Now, I get home and set the camera up and Don pitched like this (she shows a slow underhand motion and laughs!)...I hit the ball. I hit the ball. I was so excited!”

How would you describe what you are doing now?

“I have continued my interest in politics to this day. I am on the Democratic National Committee and I continue to help people I believe in to help them get elected. I am native born and I enjoy giving back to my city, so I am serving on a number of civic boards like The Music Center; “A Place Called Home”; Thelma Howard Board/California Foundation; The County Music and Arts Commission; and many other boards. I am continuing my interest in women serving in public life. Therefore, I am part of a bi-partisan project (‘The White House Project’) to elect a woman President. I get great enjoyment from spending time with my family. I have been blessed with great children and three grandchildren. My philosophy is that you have to give back to your community. I have tried to give a great amount of time to charity. I often will volunteer to take on fundraising for many of the worthwhile groups in Los Angeles.”

How close are you to the O’Malley family today?

“As I stated, I have always felt the O’Malley family is like my own family. I have found both Terry and Peter two of the most caring people I’ve ever known in my life. I have never heard Terry say an unkind word about anyone. After Walter’s death, Peter’s kindness shown to all of Walter’s friends who returned to visit Dodger Stadium and Dodgertown at Vero Beach was amazing. He took care of everyone’s needs and many of the people who came after Walter’s death were quite elderly. He had great respect for his parent’s friends. I have learned a lot about the O’Malley family, especially how to be great hosts and be gracious when you lose a ballgame. I cherish that friendship, now and forever.”

The baseball diamond at Cheviot Hills in Los Angeles is appropriately named “Roz Wyman Diamond” on July 21, 2003 in recognition of her enormous contributions to the City of Los Angeles in many areas, including city government, sports, music and the arts while serving on the City Council for 12 years (1953-65). Here, third from the left, Wyman is joined by her family members (L-R): Dr. Betty Wyman, Samantha Wyman, Eugene Wyman (baby), Brad Wyman, Dr. Peggy Giffin Wyman, Robert Wyman. Inset shot of Solome Wyman with Oliver Wyman.

THE LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL VOTE ON ORDINANCE 110204 OCTOBER 7, 1957:

Yes:

Roz Wyman

Everett Burkhalter

Ransom Callicott

James Corman

Ernest Debs

John Gibson

Gordon Hahn

Charles Navarro

Karl Rundberg

L.E. Timberlake

No:

Earle Baker

Harold Henry

John Holland

Patrick McGee

Not Voting: Edward Roybal was on vacation and did not cast a vote.

DODGER VICTORY IN CHICAGO KEY TO PASSING “PROPOSITION B”

Rosalind Wyman and Walter O’Malley were convinced that one of the most important Dodger games ever played was on June 1, 1958 in Chicago. The reason was because the “Proposition B” referendum on the June 3 ballot hinged on the public’s view of the team and whether it would vote “Yes” or “No” on the issue of the previously approved City of Los Angeles contract with the Dodgers.

Wyman felt, and she says O’Malley agreed, that the day game on June 1 was critical because a five-hour Dodgerthon aired on KTTV Channel 11 later that afternoon and evening. The Dodgerthon, chock full of celebrities, sports stars and civic leaders speaking about the benefits of “Prop B” to the city and its residents, culminated its coverage on the tarmac at Los Angeles International Airport with the triumphant arrival of the Dodgers from Chicago as thousands of adoring fans crashed the gates and celebrated.

In the day game in June, strange weather invaded the Windy City as the game-time temperature was a chilly 48 degrees with 20 mile-per-hour north winds. Stan Williams, a 20-year-old rookie, made his first major league start for the Dodgers and allowed just two hits to the Cubs. Only 3,674 brave souls attended and battled the elements at Wrigley Field.

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R runs | H hits | E errors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodgers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Chicago | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

(Scroll to the right if full line score isn’t visible.)

The Dodgers’ lone run was scored in the fourth inning and Williams made that stand up with his masterful shutout. Carl Furillo doubled to lead off the fourth inning and advanced to third on Charlie Neal’s infield out. Shortstop Don Zimmer grounded a single to left field, scoring Furillo with the game’s only run. The Dodgers finished their long road trip with an 8-9 record.

Williams posted a 19-7 record and had been the American Association’s strikeout king in 1957, while pitching for the Dodgers’ farm club in St. Paul (MN). The 6-foot-4 right-hander had only pitched in three previous innings for the Dodgers prior to getting his initial start in Chicago. He struck out three Cubs and walked two in notching his first career win.

The Dodgers arrived home in Los Angeles to nicer weather and, two days later, celebrated the passing of “Prop B.”