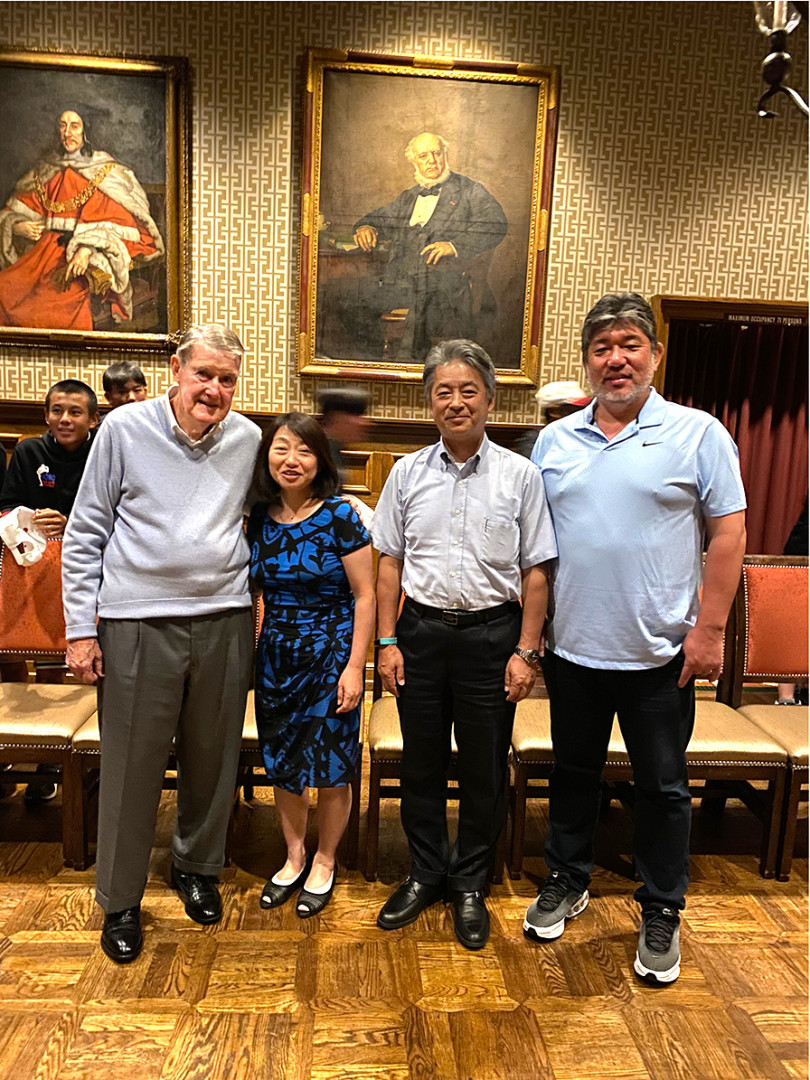

August 21, 2024, Lawry’s restaurant, Beverly Hills, (L-R): Peter O’Malley; Mami Sone, wife of the Consul General; Kenko Sone, Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles; and Japan Hall of Famer Hideo Nomo. Pioneer Dodger pitcher Nomo brought his Junior All Japan national under 15 all-stars to L.A. and O’Malley hosted the team for dinner. Consul General and his wife participated in greeting the players.

A Sports Diplomacy – Baseball holds special place in my heart.

By Kenko Sone, Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles

It has been two and a half years since I assumed my post as Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles in September 2022. Just before this, I also served as the Ambassador in charge of Sports and Budo. Although I now have fewer opportunities to play sports, I have always been a sports enthusiast, so this position was truly an ideal fit. I have long been interested in “sports diplomacy,” and among all sports, baseball holds a special place in my heart.

Looking back to my elementary school days, baseball was the most popular sport, and in Japan, baseball meant the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants. I grew up in Hokkaido, which at the time had no professional baseball team, so the Giants were the team I saw on TV most often. They were familiar, dominant, and rarely lost, making them an absolute presence in my life. I still remember the legendary Giants players I watched on the screen – Shigeo Nagashima, Sadaharu Oh, Isao Shibata, Shozo Doi, Shigeru Takada, Tsuneo Horiuchi, and more. On October 14, 1974, at Korakuen Stadium, Mr. Giants himself, Shigeo Nagashima, uttered the unforgettable words during his retirement ceremony: “The Giants will live forever.”

January 27, 1993, Tokyo, Sadaharu Oh, the world’s greatest home run hitter of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants and Japan Baseball Hall of Famer, left, and Shigeo Nagashima, Japan Baseball Hall of Fame third baseman and “Mr. Giants”, are speakers at the memorial service for Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara. A longtime assistant to Peter O’Malley, Japan Baseball Hall of Fame executive Ikuhara passed on October 26, 1992 and was an integral part of developing Dodger friendships in Japan.

I was passionate about youth baseball and once dreamed of becoming a professional player, though that dream remained just that – a dream. My high school had a competitive baseball team, and I often attended regional tournaments to cheer on my classmates aiming for Koshien, Japan’s national high school baseball championship. I admired the talented players, was fascinated by the intense strategies and managerial decisions, and was drawn into the three-hour-long dramas without scenarios. Baseball, to me, was an unparalleled sport – one that I could never turn away from.

150 Years of Japan-U.S. Baseball Friendship

Japan’s love affair with baseball began over 150 years ago, in 1872, when an American teacher, Horace Wilson, introduced the sport to students at what would later become the University of Tokyo. Since then, baseball has captivated the Japanese people.

Throughout the 150 years of Japan-U.S. baseball friendship, countless remarkable stories have emerged. Since arriving in Los Angeles, I have learned much about this shared history. Last year, I had the opportunity to watch a documentary about Japanese American baseball. One particularly moving story was that of Kenichiro Zenimura (1900-1968), a first-generation Japanese American who played baseball in the United States before World War II and even interacted with legends like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Even when he was forcibly incarcerated at the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona during the war, he formed a baseball team and organized games with local teams. His son, Tateshi Zenimura (1928-2000), later joined the Hiroshima Carp after the war. Even during a time of war, baseball remained a bridge between Japan and the United States.

Japan-U.S. baseball exchanges have so many stories including friendship games before and after the war, as well as Japanese American enthusiasm about baseball even at the time of hardship during the war. For those years, Japan has long looked up to American baseball, striving to catch up. Over time, many Major League Baseball (MLB) players came to Japan to play, making the world of the major leagues feel closer. When Sadaharu Oh surpassed Hank Aaron, who beat Babe Ruth’s then world home run record of 714, with his unique “flamingo” batting stance, Japan erupted in celebration, believing that Japanese baseball had finally caught up with America’s. Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese major leaguer in 1964-65, but even then, most Japanese – including myself – never imagined that Japanese players could one day thrive in MLB.

(L-R) Hank Aaron, Peter O’Malley, Dodger President (1970-1998), Sadaharu Oh of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, and Frank Robinson at the World Children’s Baseball Fair 20th Anniversary Awards luncheon, January 21, 2012, Riviera Country Club, Los Angeles. Japan Baseball Hall of Famer Oh surpassed Aaron for the most home runs in the world. Oh hit 868 home runs and Hall of Famer Aaron finished with 755. Hall of Famer Robinson, MLB’s first African American manager, hit 586 home runs.

The Dodgers’ Deep Connection to Japan

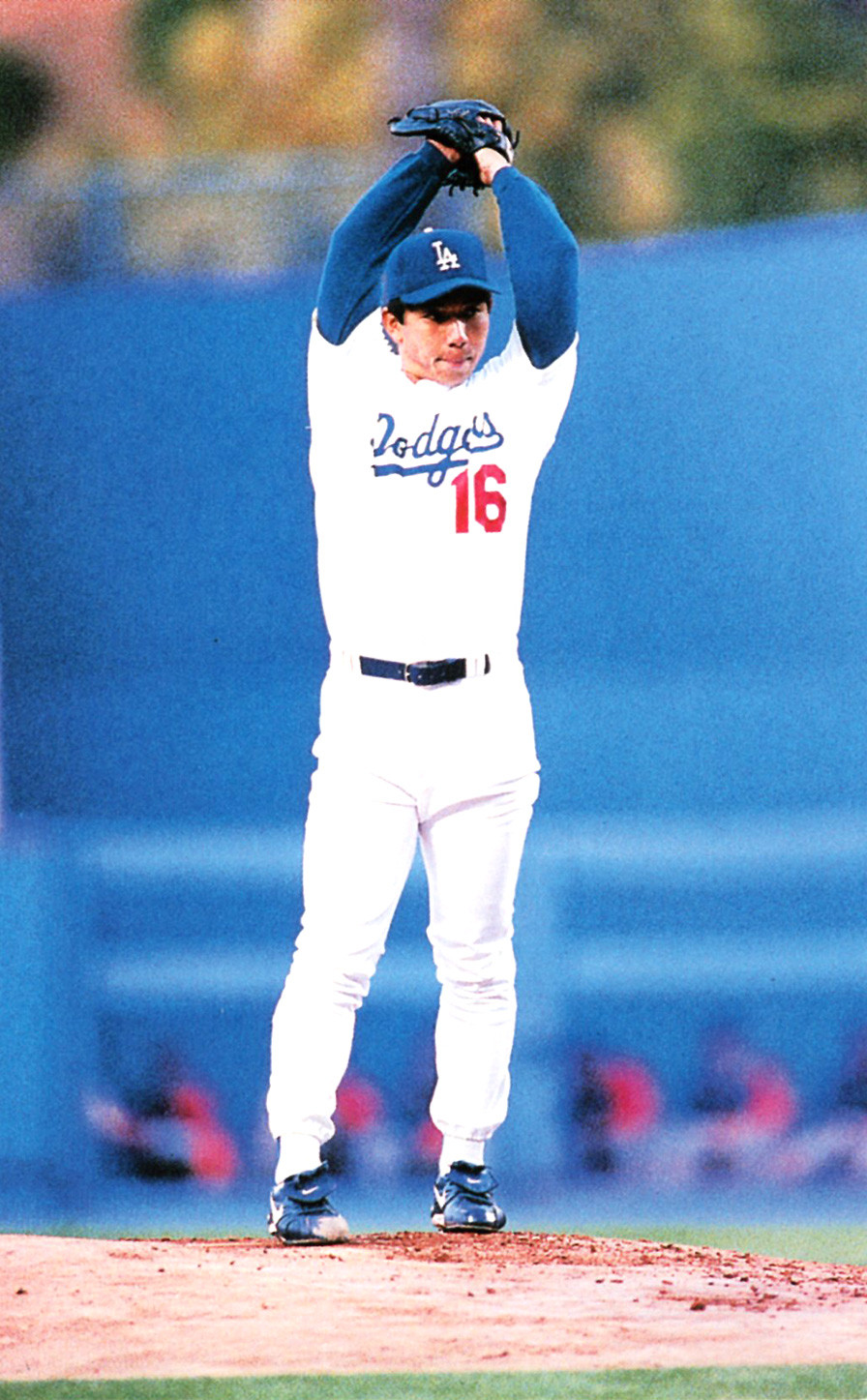

The landscape began to change in the Heisei era when Hideo Nomo left the Kintetsu Buffaloes to challenge himself in the major leagues. In 1995, he signed a minor league contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers. After making his major league debut for the first time since Murakami almost 30 years ago, he took the league by storm with his unique “Tornado” pitching style. Fans in the U.S. went wild for “NOMO Fever,” and Japanese fans, watching live broadcasts via satellite TV, began to feel that Japanese players could compete with MLB’s best. That feeling was right. Nomo was a true pioneer, paving the way for future Japanese players in the major leagues even through systemic reform.

Known as “Warrior”, Hideo Nomo’s first season in 1995 led to the global “Nomomania” as fans of baseball in the U.S. and Japan appreciated his extraordinary talent. In 1995, pioneer pitcher Nomo was named National League Rookie of the Year and led the Dodgers to the postseason.

Following Nomo’s success, many top Japanese players took on the MLB challenge – Ichiro Suzuki, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame this year, and “Godzilla” Hideki Matsui, who won the 2009 World Series MVP with the Yankees’ World Championship, are prime examples. Today, Shohei Ohtani has redefined baseball itself with his unprecedented two-way play, and many Japanese are active as leading players.

Japan’s national team’s success in the World Baseball Classic (WBC), which began in 2006, has further strengthened this confidence. The dramatic victory of the Japanese team in the 2023 WBC was a bright spot in a world struggling with economic stagnation and the COVID-19 pandemic. A friend of mine even said that he started watching baseball at stadiums again because of it.

The “Ohtani Effect” and the Japanese American Community

In 2024, excitement reached new heights when Shohei Ohtani moved from the Angels to the Dodgers, followed by Yoshinobu Yamamoto from the Orix Buffaloes. News about Ohtani’s performance dominated newspapers, TV, and social media daily, thrilling Dodgers fans. Everyone I met praised his accomplishments. When Ohtani achieved the historic milestone of 50 home runs and 50 stolen bases, securing his third MVP award, and when the Dodgers won the World Series, Los Angeles was painted in Dodgers blue. For the Japanese and Japanese American communities in Los Angeles, the presence of these two Japanese players was a tremendous source of pride. Baseball had brought Japan and the U.S. even closer together.

Beyond baseball, Ohtani’s influence extended into Japanese business and the Japanese American community. A mural of Ohtani, painted by artist Robert Vargas, was unveiled at a Japanese hotel in Little Tokyo, turning it into a popular tourist attraction. Little Tokyo, one of the oldest Japanese enclaves in the U.S., is currently designated as an “endangered neighborhood,” and efforts are underway to revitalize it. The Ohtani mural has contributed significantly to this revitalization.

The Legacy of Hideo Nomo and the Dodgers

Seeing how passionately Dodgers fans embrace Japanese players makes me believe that Nomo’s move to the Dodgers was no coincidence but rather destiny. The Dodgers have deep ties with Japan, especially through the O’Malley family, who owned the team for decades.

Upon my arrival in Los Angeles, a Japanese American Dodgers fan made a request:

“There used to be a Japanese garden at Dodger Stadium, and within it, a stone lantern donated by Sotaro Suzuki (1890-1982), who played a key role in developing Japanese professional baseball. Walter O’Malley, then the Dodgers’ owner, often visited the garden and enjoyed the Japanese atmosphere. However, due to increasing security concerns, the garden was closed and fell into disrepair. Would it be possible to restore it or at least relocate the stone lantern to a visible place?”

Though the idea seemed challenging due to costs, something unexpected happened. In March 2024, after Ohtani’s arrival at the Dodgers, the team announced that they would move the stone lantern to the stadium’s top deck. I was astonished to learn that Suzuki had developed closer friendship with O’Malley during the Brooklyn Dodgers and had donated the lantern in celebration of the Dodgers’ move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

The Future of Japan-U.S. Baseball Relations

Starting in July 2025, the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY will host an exhibition titled “Yakyu | Baseball” highlighting the history of Japan-U.S. baseball exchanges. I had the honor of attending a promotional event at Dodger Stadium, where I met the family of Ike Ikuhara (1937-1992). He was a trainee at Dodgers with the introduction of Sotaro Suzuki and then became the assistant to Chairperson Peter O’Malley. He played a key role in strengthening Japan-U.S. baseball ties. At that moment, I recognized Ikuhara was instrumental for Dodgers as well.

The key to diplomacy is people. Relationships between individuals cannot become deeply connected if one side always assumes a position of superiority or feels as though they are doing the other a favor. Now that it feels as though Japan’s “Yakyu” (baseball) has produced just as many – if not more – great players as America’s “baseball,” I feel that the sport of baseball has brought Japan and the U.S. closer together – they’re sharing more respect and interest in each other, and their bond is stronger than ever before.

Last year and this year, I had the opportunity to visit the Dodgers’ and Padres’ spring training camps in Arizona. During those visits, I learned that behind many of the players’ success are the tireless efforts of outstanding Japanese coaches, trainers, and staff. I was not only proud to see so many Japanese professionals thriving beyond the players themselves, but I also felt a deep appreciation for the inclusive and expansive nature of baseball in the United States. Mr. Peter O’Malley and Mr. Hideo Nomo continue to work together to promote youth baseball exchanges between Japan and the U.S. The efforts and accomplishments of individuals like them help sustain the Dodgers’ popularity in Los Angeles and contribute to a boom in Japanese culture.

August 20, 2015, Lawry’s restaurant, Beverly Hills, Hideo Nomo’s Junior All Japan national under 15 all-star team in first and third rows (third row on far right, former major leaguer Don Buford). (Second Row, L-R): Nobuhide Shimizu, Head Coach for Nomo’s All Japan U15 team; Annette O’Malley; Peter O’Malley; Japan Hall of Fame pitcher Nomo; Darrell Miller, MLB Vice President Youth and Facility Development; Hidehisa Horinouchi, Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles; and Sabine Horinouchi, wife of the Consul General.

This season, Roki Sasaki joined the Dodgers from the Chiba Lotte Marines. With six Japanese players now competing for teams in Southern California – the Dodgers, Padres (Yu Darvish and Yuki Matsui), and Angels (Yusei Kikuchi)—the enthusiasm is only growing. I am confident that baseball will continue to deepen Japan-U.S. relations from right here in Southern California.

Originally published on the opinion site, “Intelligence Nippon”.