Reference Biography: Walter O’Malley

Ebbets Field Revisited

However, Ebbets Field provided intimate spectator surroundings and was filled with its share of character and characters. It was the site of some of baseball’s most fascinating and memorable moments.

Ebbets Field was one of three major league ballparks in New York, along with Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds.

Dodger press pin for the 1949 World Series.

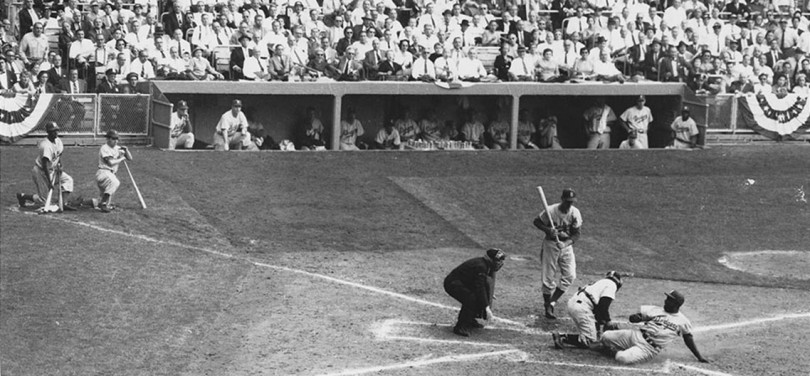

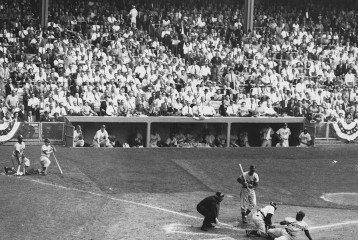

On September 28, in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, Jackie Robinson steals home for the Dodgers’ fifth run in a 6-5 loss to the New York Yankees. At the far left in the first row of the Yankee Stadium grandstand near the bunting, Dodger President Walter O’Malley is visible with his wife Kay and daughter Terry. Frank Kellert is the Dodger hitter. The Yankee catcher is Yogi Berra and the umpire is Bill Summers.

Copyright © Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.

Up to that point, Ebbets Field had played host to the 1916, 1920, 1941, 1947 and 1949 World Series. The Dodgers had not won any of the World Series. The first night game outside of Cincinnati was played there on June 15, 1938. On that night at Ebbets, Johnny Vander Meer pitched a 6-0 no-hitter, the second of his record two consecutive no-hitters. Because of an overflow crowd, the game did not start until 9:45 p.m. Vin Scully interview with Jack Lang, June 15, 1988, KABC Radio Baseball under the lights, the brainchild of Dodger President Leland S. “Larry” MacPhail, became an instant success. The first televised game in baseball history emanated from Ebbets Field on August 26, 1939. The field was home to one of the most significant moments in society and sports — the breaking of the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson took that mammoth undertaking squarely on his broad shoulders, as he figuratively and literally hit a home run and the sport has not looked back. Signing the first Black player in the majors was a serious risk that had been taken by Rickey, with approval by the Dodger organization, including O’Malley as 25 percent owner and the club’s Vice President and General Counsel, but Robinson was more than equal to the challenges, catcalls and death threats. By learning not to fight back and keeping his emotions in check, while performing to MVP levels between the white lines, the uniquely-qualified Robinson opened the door for more black players in the majors.

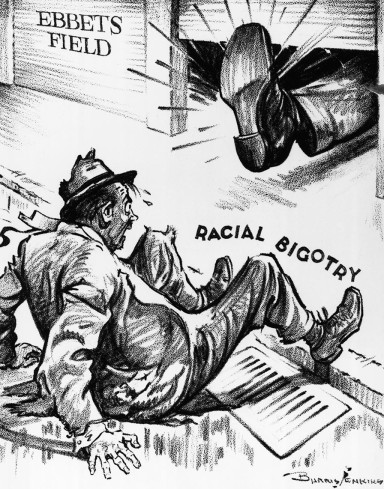

As Jackie Robinson opens the way for African-American players to perform in Major League Baseball, the Dodgers continue to add more African-American players to the roster, including such stars as Dan Bankhead, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Joe Black and Jim Gilliam. In this March 23, 1953 cartoon by Burris Jenkins, a boot is kicking a man out of Ebbets Field with “Racial Bigotry” on the sidewalk. The original was entitled, “Where He Belongs.”

© Bettman/Corbis

In Ebbets Field, characters abounded. Legendary leather-lunged fans like Hilda Chester, whose voice could be heard above the din of the crowd shouting at players, along with her cowbells, were classic. So, too, was ballpark organist Gladys Goodding, who is the answer to a popular trivia question, “Who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Rangers and New York Knicks?” How about the zany antics by members of the Dodger Sym-Phony band, who drummed up excitement with their mock playing ability?

O’Malley once even staged a “Music Appreciation Night” at Ebbets on August 13, 1951 when fans bringing a musical instrument were admitted free. “Among the Dodger fans is a group of seven men, two of them professional musicians, who parade through the park during games serenading the spectators, playing salutes to the Dodgers and ragging the opposition eight to the bar — or worse,” wrote Milton Gross. “Except for being allowed free admission to the games, they are not paid. The two pros are card-carrying members of Local 802, Musicians’ Union. The union protested their playing in a unit with nonunion members. O’Malley met the crisis by reducing it to such an absurdity that the union pulled in its French horns in sheer embarrassment. What he did was stage a ‘Music Appreciation Night.’ Mayor Vincent Impellitteri (who officially declared it ‘Music Depreciation Night’) and members of the New York City Board of Estimate sang, Take Me Out to the Ball Game, accompanied by the most horrible cacophony ever perpetrated in the name of music...he turned a labor difficulty into a publicity bonanza that was carried on front pages all over the country. Immediately after, Local 802, fearful of its own good reputation, withdrew its protest and the “Dodger Sym-Phony” was back in business.” Milton Gross, The Artful O’Malley and the Dodgers, True, May 1954 A total of 2,426 musicians, or at least fans with musical instruments, showed up that night and the New York World-Telegram and Sun reported in retrospect, “The din was terrific. A flatted fifth or two may still be bouncing around in the left field seats.” Alan St. James, New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 16, 1956

Walter O’Malley sits in with the Dodger “Sym-Phony” band.

Television personality Francis J. Felton, better known to all as “Happy” Felton, organized “The Knothole Gang” which was another Ebbets Field regular feature, enabling hundreds of thousands of local youngsters to attend games through a Dodger-sponsored donation of tickets. While fishing with then-Vice President O’Malley, Felton thought of the idea and O’Malley agreed it was a good one. He arranged for Felton to be interviewed by President Rickey. His popular pregame television program was launched in 1949, as Felton brought children onto the field to interact with Dodger players and learn more about baseball.

Another innovative idea was the addition of an artesian well located under the Dodger bullpen to provide water used in the Ebbets Field sprinkler system. Dave Anderson, New York Times, April 6, 1955

In the 1950s, the Dodgers had one of the most talented teams on the field. Led by Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges, Carl Furillo, Jim Gilliam, Carl Erskine, Johnny Podres, Don Newcombe and Clem Labine, who made a mark that has been well-chronicled in baseball history and still has significance to the game today. Affectionately known as “Bums” in the Borough of Brooklyn, O’Malley responded to a letter from Joe Williams of the New York World-Telegram on October 12, 1953 regarding his feelings about the term.

(L-R): Walter O’Malley; Carl Furillo; Andy Pafko; Carl Erskine; Roy Campanella; Manager Charlie Dressen. Walter O’Malley presents a $500 check to pitcher Carl Erskine following his 5-0 no-hitter against the Chicago Cubs on June 19, 1952.

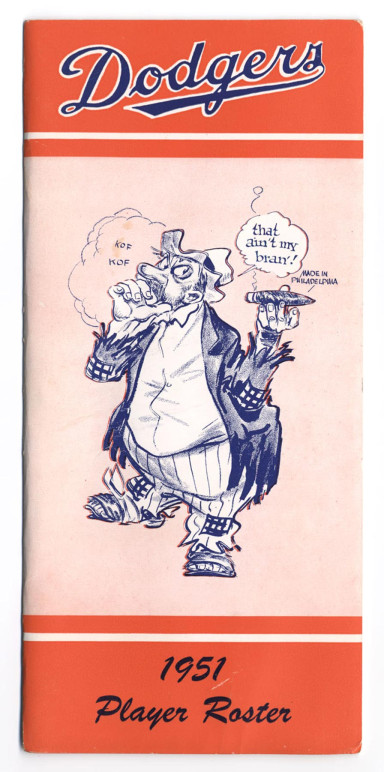

The Brooklyn “Bum” character, penned by the New York World-Telegram’s Willard Mullin, expresses optimism for the 1951 season.

Copyright © Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.

O’Malley wrote, “As for the origin of the Bum, I think we can blame, or better yet salute, your pal Willard Mullin. The Bum is Willard’s brain child, and is, to my mind, a wonderful little creature indeed. The Dodgers, you know, are more than just a baseball team. They mean something to the people who have never seen a ball game and who wouldn’t know where first base is if they did go to one. The Dodgers are a symbol of the underdog, and well — so is the Bum...Willard popularized the little fellow after hearing the Faithful exhort their ‘bums’ to greater heights at Ebbets Field and through the years this has become a term of endearment rather than of contempt. I think this is mirrored in the face of Willard’s character. He is ragged, and occasionally he is a bit battle-scarred, but he is proud, defiant and persistent. And best of all, he has the mischievous twinkle of the downtrodden in his eye which has always spelled trouble for the high and mighty of this earth.”