Reference Biography: Walter O’Malley

Searching for New Stadium Answers

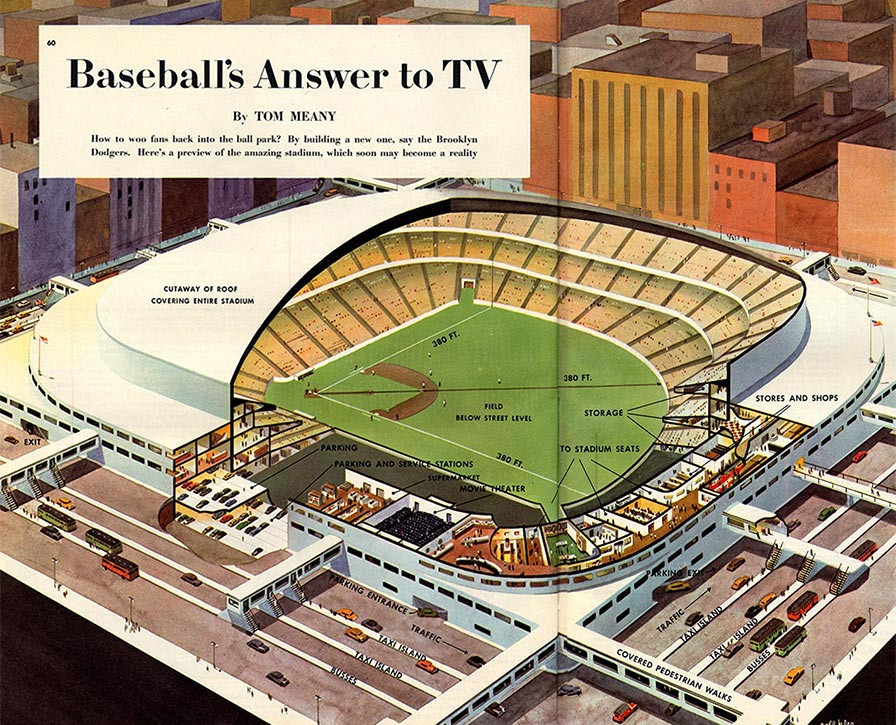

On June 17, 1952, O’Malley wrote a letter to The Brooklyn Eagle publisher Frank Schroth about the possibility of building a stadium with a retractable dome. He wrote, “I believe Brooklyn needs a modern athletic stadium seating approximately 52,000 people. A modern stadium with a movable roof would provide convention facilities unequalled elsewhere. Such a stadium could house motor boat, automobile, flower, sportsman and other shows and attractions. Such a stadium would have to be strategically located to give maximum convenience for rapid transit patrons. Present and future parkways should be designed to provide accessibility. The stadium could offer all year round parking facilities.

Collier’s magazine on September 27, 1952 illustrates one of the Dodgers’ new ballpark proposals for Brooklyn.

“Many special purposes to which the stadium could be put would include skating on artificial ice in the winter months and roller skating all year round. Such a stadium would lend itself to top attraction football games, boxing and basketball events and other recognized sports.

“We have definite ideas as to where such a stadium should be located and the site would be nearer Wall Street and Rockefeller Centre [sic] than the Polo Grounds, Yankee Stadium or Ebbets Field.

“Brooklyn has an international reputation as a baseball town. Much of the mention that the Borough receives, and some of it facetious, is in reference to baseball. If this is an asset, I believe it is, let us capitalize on the fact and encourage the erection of the first all purpose sports and convention arena indoor and outdoor in Brooklyn.

“I wish this were Bob Moses’ idea and not mine as he has the know how and zeal to see it through.”

O’Malley’s forward thinking of an all-purpose domed stadium with a movable (or retractable) roof was also years ahead of its time.

As part of the player development system, it was Rickey’s vision to have a baseball factory where the players were the widgets and he could push the best ones up the ladder to the majors. In his baseball breeding ground, more than 600 players participated on 26 teams in the early years of Dodgertown in Vero Beach, FL. The players would eat in the mess hall, sleep in the Naval barracks without heating or air conditioning and train on the numerous fields, in the batting cages and pitchers’ strings area. Every Dodger great trained at Vero Beach, after Brooklyn set up camp there in 1948 on the recommendation of local businessman Bud Holman, the influential General Motors automobile dealer and Eastern Air Lines director. O’Malley saw the long-term potential of the small Vero Beach community, an East Coast hamlet with not much happening except the airport.

But with his vision of how to develop the complex, O’Malley took the bare bones former U.S. Naval Air Station base with its barracks and simply elevated the training camp to a whole new level, first signing a 21-year lease extension with Vero Beach on January 30, 1952 and later purchasing the land (nearly 400 acres). The Dodgers helped to put the Florida community on the map and grow into a resort and retirement area, as the “snow birds” visited the training camp from New York, New Jersey and other points north.

Immediately, O’Malley wanted to upgrade the camp and make its stadium a more appealing venue for fans. On July 16, 1952, O’Malley awarded the contract to build the new ballpark to H.J. Osborne, who had 90 days to complete the “grading, concrete, fill work, ramps and fence.” Julie Autumn Luster, 2002 Dodgers Spring Training Yearbook, “Holman Celebrates Half a Century” Other contracts were awarded to complete the seats, press box, lights and refreshment stands. The seating area was originally to be 4,200, but was later expanded to 5,000 capacity.

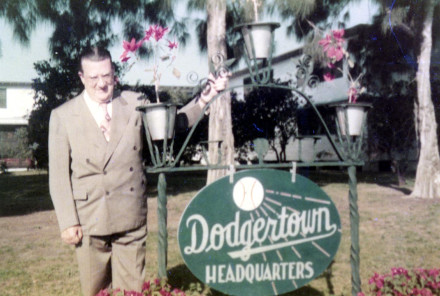

The Dodgers moved their spring training headquarters to Vero Beach, FL in 1948.

Walter O’Malley’s many improvements at Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida included designing and building Holman Stadium, which opened on March 11, 1953. The baseball field at the bottom, just beyond the heart-shaped lake, was used for pre-season games for Dodger minor leaguers and would eventually be the area where O’Malley created the Dodgertown Golf Club, a nine-hole public course so all Dodger players could enjoy a game of golf when other local courses were private.

(L-R): Captain Emil Praeger, designer; Bud Holman, prominent Vero Beach business and community leader; Walter O’Malley; Herman Osborne, concrete contractor; Jesse Swords, land preparation contractor. Circa 1952, a model of Holman Stadium, engineered and designed by Capt. Emil Praeger (far left), and Walter O’Malley is on display. The ballpark was named in honor of Bud Holman who brought the Dodgers and their many farm teams to Vero Beach, Florida beginning in 1948. O’Malley privately built Holman Stadium.

On March 11, 1953, O’Malley dedicated “Holman Stadium,” which was designed and engineered by the trusted Capt. Emil Praeger, the intimate new ballpark named in honor of the man who had wooed the Dodgers to Vero Beach. Despite reports that architect Norman Bel Geddes had designed Holman Stadium, O’Malley wrote the words, “Geddes has nothing to do with this job” on an official internal document. Bel Geddes had, however, been asked earlier by O’Malley to evaluate Ebbets Field for possible expansion and other new stadium ideas. It well may have been a first major test for the talented Praeger in O’Malley’s circle which he passed with flying colors. The cost-efficient stadium was built of concrete with steel reinforcing. A plaque from O’Malley to the Vero Beach community commemorating the opening day ceremonies read, “The Brooklyn Dodgers dedicate Holman Stadium To Honor Bud L. Holman of the friendly City of Vero Beach.” Playing before many distinguished guests, the Dodgers won the first game played at Holman Stadium, 4-2, over the Philadelphia Athletics with an overflow crowd of 5,532 fans. Connie Mack, the owner of the Athletics and longtime former manager, also took in the opener.

Throughout his presidency, Walter O’Malley improved, developed and maintained the facilities at Dodgertown, the Dodgers’ spring training home in Vero Beach.

Hall of Fame Manager and Philadelphia Athletics part-owner Connie Mack greets Walter O’Malley during the first exhibition game at Holman Stadium, Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida on March 11, 1953. The Dodgers defeated the Philadelphia Athletics, 4-2.

It was the Dodgers who would not be denied in the next two seasons, as they won back-to-back National League Pennants in 1952 and 1953, although they would lose both seasons to the rival New York Yankees in the World Series. The powerful 1953 Dodgers with such stars as Robinson, Reese, Campanella, Snider, Hodges, Furillo, Newcombe, Erskine, Labine, Gilliam and Preacher Roe, won a club-record 105 games. Dressen, strongly influenced by his wife Ruth who drafted a letter to O’Malley, felt that he should be rewarded for his success with a long-term contract (preferably one for three years), instead of the routine one-year pact, a policy which had been established by Rickey. “So forcefully was it worded that O’Malley said he ‘didn’t want it kicking around in the offices’ of the Dodgers. He returned the letter to Dressen and magnanimously told him to forget he ever wrote it.” Ed Pollock, Sports, The Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia, PA, October 16, 1953 As Dressen wouldn’t budge from his stance, O’Malley disagreed with his position and decided to find a managerial replacement.

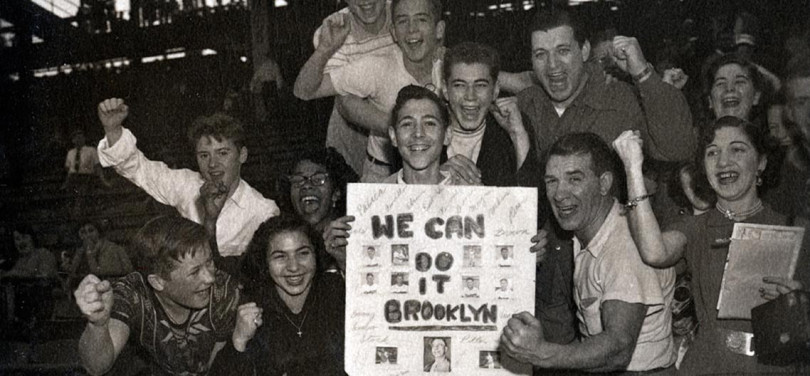

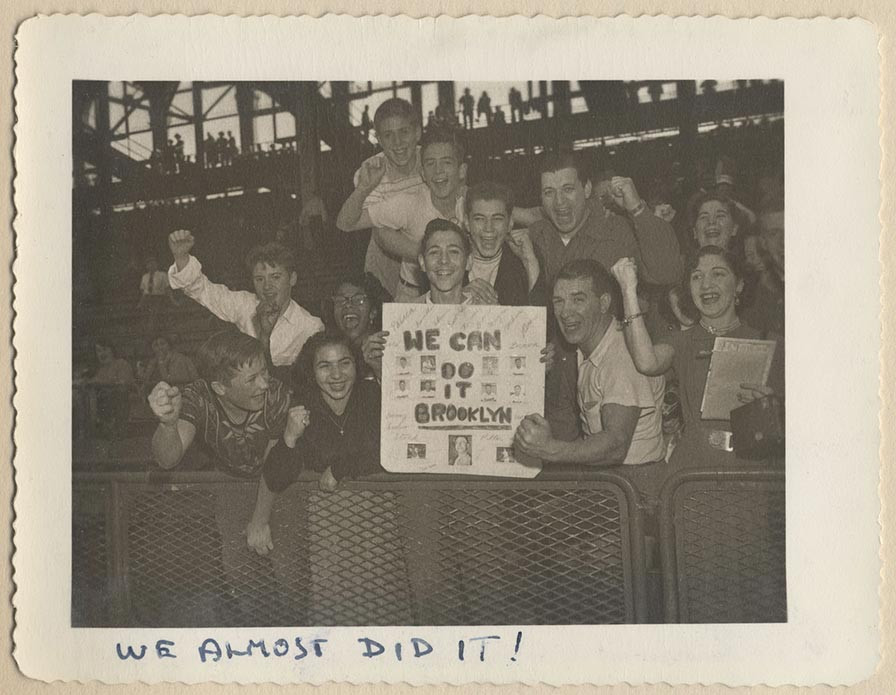

Fans at Ebbets Field watched the Dodgers win four National League Pennants between 1952-56.

A significant letter was written by O’Malley to his old friend and mentor, George V. McLaughlin on June 18, 1953 in which he states, “Be good enough to let me have the benefit of your thoughts on the following: I would also like to talk the problem out with Bob Moses. We need a new ball park. It should be privately built and maintained. The Milwaukee story is an interesting one but I would prefer to exploit the possibility of private ownership. We could not acquire land suitably located without the condemnation assistance of the government. Title 1 of the Federal Housing Act of 1949 would probably have to be used. I am convinced that a ball park would have to have some use in addition to baseball in order to justify capital investment.

“I have been interested in the success of the Battery garage which, I believe, cost approximately $3,000 a car to build. There are one or two sites in downtown Brooklyn where a study might show that a parking garage would be successful, particularly if supplemented by patrons of a sports stadium...A combination parking garage and ball field would make an improvement that could justify Title 1 action.

“In 1947, I persuaded John Smith and Branch Rickey to retain Emil Praeger to make study of possible sites for a new ball park. In March 1948, Praeger recommended a site in an interesting report together with exhibits, diagrams and plans. Last year I asked Praeger to bring his report up to date and to advise me if such a stadium were to be built could it also serve as a parking garage. He has recently submitted several studies showing that anywhere from 1000 to 1750 cars could be accommodated in what would otherwise be the waste space under the lower stands.

“...In the meantime I have studied the interesting plans for the Ft. Greene slum clearance and improvements. Query: Is it too late to relocate some of the planned facilities provided for in the Ft. Greene plan, particularly the apartments, so that a ball park and parking garage could be located at the site picked in the 1948 Praeger report.

“...We can only park 850 cars at Ebbets Field in the odd and scattered parking lots. At the first night game Brooklyn played in Milwaukee last month 8,752 cars were parked for the game. Lack of parking accommodations, more than anything else, TV included, keeps people from coming to our games. Ebbets Field was built in the trolley car era. There are no trolleys to speak of today but there are automobiles and intelligently planned parkways.

“This proposal would bring activity to the Borough Hall section at times when rapid transit, tunnel, bridge and highway facilities are relatively slack. A new stadium properly located would house attractive sports events in addition to baseball. Do you think there is at least the germ of an idea here?”

McLaughlin responded by letter four days later: “I have your letter of the 18th and by this time you probably have heard from Bob Moses. There is nothing we can do, so far as the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority is concerned; in fact, it was a stretch for us to get the law amended to take care of the Coliseum. I am not inclined to believe that Bob will go along with the idea, because, with the City struggling to assemble as much funds as it can for slum clearance and other public improvements, I don’t think you would find members of the Board of Estimate sympathetic to using any Government grant for the construction of a ball park at this time. Sincerely, Geo”

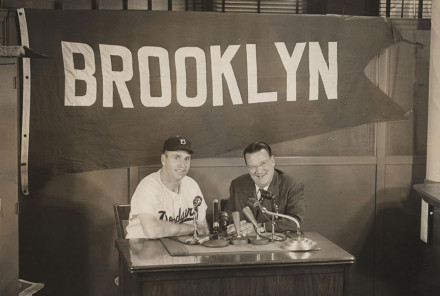

Walter O’Malley congratulates new Dodger Manager Walter Alston at his first contract signing on Nov. 24, 1953.

Moses, who received a copy of the letter, also answered O’Malley’s letter by writing, “Various reliable people had already told me of your recent efforts to substitute a new Brooklyn ball field for the Title One slum clearance project at Fort Greene on which agreement was reached some time ago involving all the responsible federal and local officials. The law and facts on this matter have been repeatedly stated. This project has been delayed for a short time awaiting the decision of the Court of Appeals in a basic case involving broad constitutional questions and the interpretation of Title One of the federal law.

“We do not believe that the law would permit the use of the Fort Greene Title One area to establish a new ball field in any case. It is true that the New York Coliseum is a part of slum clearance at Columbus Circle under Title One but this project was specifically authorized and declared to be a public purpose by State law adopted under the Home Rule section of the Constitution. Moreover the federal provisions requiring predominantly residential uses have been complied with.

“Let me add that there are other reasons aside from those of law and sound policy why your plan is not one which justifies the exercise of the power of eminent domain not to speak of the use of public funds to reduce the cost of land. Our Slum Clearance Committee cannot be used to encourage speculation in baseball enterprises. You are, of course, the best judge as to whether in fact a new Dodger Stadium would be anything but a white elephant, and whether the extension of your present property with additional surface and other parking facilities would not meet every problem you mention except perhaps television competition. I am sorry to have to write this letter but I know you want it straight from the shoulder.” Robert Moses letter to Walter O’Malley, June 22, 1953

O’Malley also had to take care of business on the field, as he hired a virtual unknown when he replaced Dressen, naming 42-year-old Walter Alston manager of the Dodgers on November 24, 1953. Headlines exclaimed “Walt Who?” but that did not deter the astute O’Malley from his enthusiasm over his selection of a skilled baseball man from Darrtown, OH whose career had culminated in only one major league game as a first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals. Alston had thrived in the Dodger organization, piloting the Montreal Royals to the “Little World Series” championship against the New York Yankees’ Kansas City club in 1953. He had also won the American Association pennant at St. Paul (MN) in 1948 and three times captured the flag in Montreal. Alston would successfully guide the ballclub for the next 23 seasons, cementing his name and legacy in Dodger lore. In each of those years, Alston had one-year contracts as he and O’Malley were mutually loyal. It was the way that O’Malley preferred to hire his skipper.

Walter Alston and Walter O’Malley appear at the manager’s introductory news conference on Nov. 24, 1953.

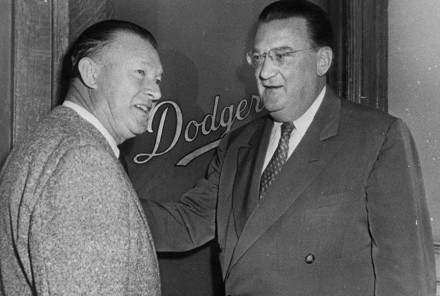

Charlie Dressen and Walter O’Malley following Dressen’s departure from the Brooklyn Dodgers after the 1953 season.

Asked at the press conference to introduce Alston what would happen following the 1954 season if the Dodgers did not win the World Series, O’Malley kiddingly replied, “Around December we’ll have to take that up, unless his wife writes a letter in the meantime.” Michael Gaven, New York Journal-American, November 24, 1953

In late June of 1954, Parks Commissioner Moses wrote Brooklyn Daily Eagle publisher Frank Schroth that O’Malley and the Dodgers should work on improving Ebbets Field and Moses’ office would assist in solving the parking problem. To O’Malley that was not a viable solution because his studies showed a make-over of Ebbets Field would be as costly as, or more expensive than, a new ballpark with all modern amenities already included. Besides, Ebbets Field sat on a small, landlocked parcel of land that would have made it difficult to remodel and add sufficient parking.